Strange Animals Podcast

Episode 402: The Hoop Snake and Friends

Thanks to Nora and Richard from NC this week as we learn about some scary-sounding reptiles, including the hoop snake!

Further reading:

The Story of How the Giant “Terror Skink” Was Presumed Extinct, Then Rediscovered

San Diego’s Rattlesnakes and What To Do When They’re on Your Property

Snake that cartwheels away from predators described for the first time

Giant new snake species identified in the Amazon

The terror skink, AKA Bocourt’s terrific skink [photo by DECOURT Théo – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=116258516]:

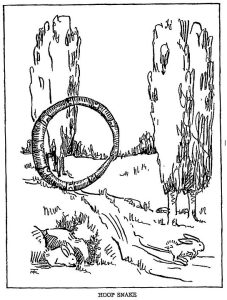

The hoop snake according to folklore:

The sidewinder rattlesnake [photo taken from this article]:

The dwarf reed snake [photo by Evan Quah, from page linked above]:

The green anaconda [photo by MKAMPIS – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=62039578]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

As monster month continues, we’re going to look at some weird and kind of scary, or at least scary-sounding, snakes and lizards. Thanks to Nora and Richard from NC for their suggestions this week!

We’ll start with the terror skink, whose name should inspire terror, but it’s also called Bocourt’s terrific skink, which is a name that should inspire joy. Which is it, terror or joy? I suppose it depends on your mood and how you feel about lizards in general. All skinks are lizards but not all lizards are skinks, by the way.

The terror or possibly terrific skink lives on two tiny islets, which are miniature islands. These islets are themselves off the coast of an island called the Isle of Pines, but in French, which I cannot pronounce. The Isle of Pines is only 8 miles wide and 9 miles long, or 13 by 15 km, and is itself off the coast of the bigger island of New Caledonia. All these islands lie east of Australia. Technically the islets where the skink lives are off the coast of another islet that is itself off the coast of the Isle of Pines, which is off the coast of New Caledonia, but where exactly it lives is kept a secret by the scientists studying it.

The skink was described in 1876 but only known from a single specimen captured on New Caledonia around 1870, and after that it wasn’t seen again and was presumed extinct. Colonists and explorers brought rats and other invasive animals to the New Caledonian islands, which together with habitat loss have caused many other native species to go extinct.

But in December 2003, a scientific expedition studying sea snakes around the New Caledonian islands caught a big lizard no one recognized. Once the expedition members realized it was a terror skink, alive and well, they took lots of pictures and videos of it and then released it back into the wild. Since then, more specimens have been discovered during four different expeditions, but only on the islets, not on any of the bigger islands. It’s so critically endangered that its location has to be kept secret, because if someone captures some of the lizards to sell on the illegal pet market, the species could easily be driven to extinction.

The terror skink is gray-brown with darker stripes, a long tail, and a slightly downturned mouth that makes it look grumpy. It grows about 20 inches long, or 50 cm, including its tail. This is really big for a skink, so technically it’s a giant skink.

It gets the name terror skink from its size and from its teeth, which are large and curved like fangs. It mainly eats one particular species of land crab, which is why its jaws are so strong and its teeth are so sharp, so it can bite through the crab’s exoskeleton.

Another lizard with a spooky name that has been presumed extinct is the gray ghost lizard, suggested by Richard from NC. It’s more properly called the giant Tongan ground skink, and it’s native to some more South Pacific islands—specifically, the Tongan Islands. These islands are even farther east from Australia than the New Caledonian islands, and are actually closer to New Zealand than to Australia, although they’re not really very close to either.

The giant Tongan ground skink was described in 1839 from two specimens collected in the late 1820s on Tongatapu Island. They’re the only two specimens known and the lizard is considered extinct, especially considering that these days, the island is almost completed deforested and rats, dogs, and cats have been introduced to it, which has driven many species to extinction.

But after the terror skink was rediscovered, scientists started to wonder if the gray ghost might still be around. It was called the gray ghost because it was so hard to see, since it was dark gray in color. The native Tongan people considered it a good omen if someone saw one, since it was so rare.

A paper published in early 2024 suggests that the gray ghost might be living on some smaller islands where forests still remain, and also suggested that it might be nocturnal and a burrowing skink. That would explain why it was so rarely seen by the people who lived on its island when it was still alive.

We know basically nothing about the gray ghost. Hopefully an expedition to the smaller Tongan islands will rediscover it so we can learn more about it and protect it.

Richard from NC also suggested we talk about the hoop snake, an animal of folklore. I remember reading about it as a kid in a book about American folklore animals, most of which were clearly jokey and not meant to seem real. The hoop snake sounded more realistic.

The hoop snake was supposed to be a long, slender snake that slithered around normally most of the time, but when it needed to move faster, it would grab the end of its tail in its mouth and roll like a wheel, or a hoop. Some versions of the story had the snake rolling along with the tip of its tail pointed forward, and since the tail was supposed to be sharp and venomous, it would roll after you so fast that when its tail stabbed you, you’d drop dead. The only way to escape would be to jump behind a tree. The tail would stab the tree instead and you could run away while the hoop snake was trying to unstick its tail. The venom in its tail was supposed to be so deadly that the tree would turn black and die. Other versions of the story said you had to jump through the snake’s hoop to confuse it, which would allow you to get away safely.

All this is weird, to say the least, but some snakes do have ways of traveling that are unusual. The sidewinder, for instance, is a real species of rattlesnake from the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. It grows around 2 ½ feet long, or 80 cm, and has pointy scales, called keeled scales, including a pair above its eyes that make it look like it has little horns. Since it’s a type of rattlesnake, it has a rattle that it can shake to make a loud warning noise. It’s mostly brown in color, or sometimes pinkish, yellowish, or even whitish, with darker stripes or blotches down its back. Its coloration helps camouflage it against the ground, and it will actually change color slightly depending on the temperature. This is something other rattlesnakes can do too.

The sidewinder lives in desert conditions where it has to travel through loose sand, and the sand is also extremely hot. While the snake can travel normally when it wants to, it sidewinds to move quickly over loose sand or very hot sand that might burn it. It lifts most of its body up so that it’s only touching the ground in two places, then undulates its body so that the sections touching the ground constantly move. That way no part of its body has to stay in contact with hot sand for more than a split second. It travels in a path that runs diagonal to the direction its body is pointing. That sounds complicated, but it’s easy for the snake. It’s not even the only snake that can travel by sidewinding. Other desert-living snakes travel across hot sand by sidewinding, including several species from Africa, but just about any snake can do it if they need to. It allows a snake to travel over surfaces that are too slippery for its belly scales to get a grip.

The story of the hoop snake might be based on garbled reports of sidewinders, but it might just be a completely invented animal. The hoop snake story is found in other parts of the world too, especially Australia, although it dates back to at least the late 18th century in the United States.

No snake in the world has the anatomy to allow it to roll like a hoop without hurting itself. But there is one other snake that does something very similar, called cartwheeling. It’s the dwarf reed snake that lives in Malaysia and other parts of southeast Asia. Reed snakes aren’t very well known to science, so this cartwheeling activity wasn’t documented scientifically until recently, with the study published in 2023. Reed snakes are nocturnal and spend most of the daytime hiding under rocks or logs, or buried in dead leaves or sand, so they’re not seen very often by people. The dwarf reed snake is slender and only grows about 10 inches long, or 25 cm.

Some small snakes can jump short distances by pushing their tails against the ground. The dwarf reed snake does something similar, but more complicated. It pushes off with its tail, with its body curved in a sort of S shape. It lands on its head and rolls over completely, head to tail, and then pushes off the ground again with its tail. It can move extremely fast in this way to get away from predators, but it takes a whole lot of energy. But when it’s moving downhill, with gravity on its side, it can continue to cartwheel longer.

Cartwheeling isn’t something the snake does often, and it’s rare that a human would ever observe it. But just like sidewinding, some scientists think cartwheeling might be a motion that more snakes can do if they really need to. Maybe that’s where the hoop snake legend started.

Let’s finish with a suggestion from Nora, who wanted to learn more about the green anaconda. That’s a scary snake for sure, because it happens to be the biggest snake alive today, and almost the longest, as far as we know.

The green anaconda lives throughout much of South America, although not in Patagonia because like most reptiles, it needs warm weather to function. It’s a beautiful olive green with black blotches, and it’s a big, bulky snake. It spends a lot of time in the water, which helps it stay cool in hot weather and helps support its weight comfortably, and its eyes are near the top of its head so it can watch for prey while it’s mostly submerged.

The anaconda is a member of the boa family and is a constrictor. It’s not venomous, but you really don’t want a hug from a hungry anaconda. Its body is bulky because it’s incredibly strong, and once it starts to contract its muscles, whatever it’s constricting has only minutes left to live. It can kill animals as large as caimans, which are a type of crocodile, tapirs, capybaras, deer, and even jaguars. For the most part, though, an anaconda doesn’t want to bother with prey that could potentially hurt it, so it will stick with smaller animals that are still big enough to make it worth the effort. And yes, it is possible that an anaconda in the wild could kill and eat a human, but there’s no reliable evidence that it’s ever happened.

It’s hard to know exactly how long and how heavy an anaconda can get. There are lots of stories of 30-foot, or 9-meter snakes, but that seems to be a wild exaggeration. Snakes are stretchy, and a healthy live snake doesn’t really want to stretch out straight to be measured. A dead snake is even stretchier than a live snake. A shed snakeskin is the stretchiest of all, and usually has stretched out quite a bit when the snake was shedding. A good estimate is that a big female anaconda can grow about 20 feet long, or 6 meters, and can weigh around 250 lbs, or 114 kg. Males are smaller on average, and a wild snake will weigh less than one kept in captivity.

There are definitely larger individual anacondas, especially considering that reptiles continue to grow throughout their lives, but they’re probably not that much longer. This is only a little shorter than the reticulated python, which can definitely grow up to 23 feet long, or 7 meters.

One important detail about the size of the green anaconda is that the biggest snakes live in the Amazon rainforest–but the Amazon rainforest is really hard for humans to navigate safely and most anacondas killed or kept in captivity lived in other parts of South America. So there might easily be anacondas in the rainforest that are much bigger than the ones scientists have been able to measure so far.

In February of 2024, a journal article was published about a 2022 National Geographic nature documentary and scientific expedition to the Amazon basin to find a rumored population of extra-large anacondas. The expedition was led by hunters from the Waorani people, who consider the snakes sacred, and the hunters and their chief were credited as co-authors of the paper, as they should be since they provided so much information.

The scientists were able to examine several fully grown anacondas and take tiny tissue and blood samples to test later. They were astounded at the size of the snakes they found, including one that measured 20 and a half feet long, or 6.3 meters. The hunters reported seeing snakes that they estimated as over 24 feet long, or 7.5 meters, that might have weighed as much as 500 pounds, or 226 kg.

Beyond mere size, though, is something very interesting, which the scientists learned when they got home and ran genetic tests. The anacondas are actually quite different genetically from other anacondas known to science, that live farther south. They described the snake as a new species, which they refer to as the northern green anaconda, but it has actually resulted in a lot of controversy. Some scientists agree that the northern green anaconda is a separate species, others think it’s only a subspecies of the green anaconda, while others think the genetic differences are minor and separating the northern green anaconda from other anacondas isn’t justified by the evidence.

Obviously scientists need to follow up and learn more about the anacondas, but one thing is clear. There are some really, really big snakes out there in the Amazon.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!

Visit Podcast Website

Visit Podcast Website RSS Podcast Feed

RSS Podcast Feed Subscribe

Subscribe

Add to MyCast

Add to MyCast