The Creative Penn Podcast For Writers

The Seasons Of Writing With Jacqueline Suskin

How can you adopt the seasons of nature in your writing? How can you allow periods of rest as well as abundance? Jacqueline Suskin explores these ideas and more in this interview.

In the intro, thoughts on children's book publishing [Always Take Notes Podcast]; how to market a memoir as an indie author [ALLi]; A desperate quest. A holy relic. A race against time. Spear of Destiny is live on Kickstarter!; What is Kickstarter and why am I launching there?, I'm on the Wordslinger Podcast talking about marketing later books in a series.

Book cover designer Stuart Bache on AI for book covers [Brave New Bookshelf]; OpenAI signs licensing deals with The Atlantic, Vox Media, and NewsCorp [OpenAI]

Today's show is sponsored by Draft2Digital, self-publishing with support, where you can get free formatting, free distribution to multiple stores, and a host of other benefits. Just go to www.draft2digital to get started.

This show is also supported by my Patrons. Join my Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn

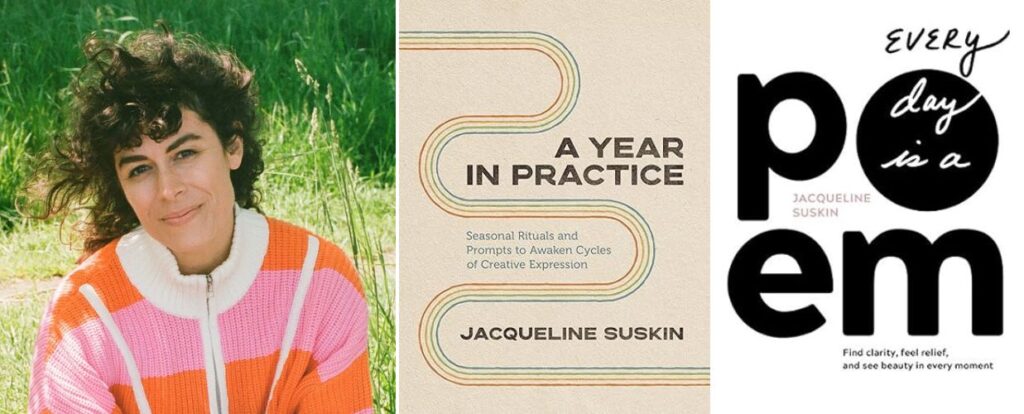

Jacqueline Suskin is a poet, author, speaker, and creative consultant. Her latest book is A Year In Practice: Seasonal Rituals And Prompts To Awaken Cycles Of Creative Expression.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Writing a poem quickly, live and in person, or order

- Choosing the poems that go into a collection and knowing when it's finished

- The physical beauty of layout on the page

- Embracing the seasons of life and creativity

- Trust emergence

- Choosing the “easeful” path for your next project

- Celebrating our creative accomplishments while continuing our journey

- Practices to help us slow down

- ‘The veil is thin' and how it manifests in our work

You can find Jacqueline at JacquelineSuskin.com.

Transcript of Interview with Jacqueline Suskin

Joanna: Jacqueline Suskin is a poet, author, speaker, and creative consultant. Her latest book is A Year In Practice: Seasonal Rituals And Prompts To Awaken Cycles Of Creative Expression. So welcome to the show, Jacqueline.

Jacqueline: Thanks so much for having me.

Joanna: I'm excited to talk to you today. First up, just—

Tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing poetry and books.

Jacqueline: I've been writing ever since I was a little kid. I feel like I'm one of those people who just sort of knew at a young age that words were the world I wanted to live in.

I didn't really know what that meant for a long time. I didn't know I was writing poems. Then the older I got, the more I was familiarized with that world, and I thought, oh, I've just always been a poet. So I ended up going to university to study poetry, and getting a degree in poetry, and then just continued to follow that.

It's really led me to some pretty incredible places, including this project that I've done for a long time called Poem Store, where for about 12 years, my only job was to take my typewriter around to public places and write poems for people on the spot.

So I really got this sort of direct connection with the way that everyday people connect with poetry. That has definitely illuminated my path as a writer.

Joanna: That is so crazy. I mean, what possessed you to do that? How did you make that a living? I mean, I have seen some people do that. As an introvert who just doesn't really want to speak to people in general, I just find that utterly terrifying.

Tell us a bit more about Poem Store.

Jacqueline: I mean, honestly, it happened by chance. I just met someone in Oakland who was doing that, and he found out I was a poet, and he invited me to come try it with him.

I had just purchased a typewriter, which was so strange, everything kind of aligned magically like that. That was in 2009. I did that as an experiment just to see if I could, and then I just realized almost immediately how special it was.

It was the perfect combination of my two skills. One is writing and the other is to connect deeply with people. So I just let myself follow it and see how far I could take it. I had no idea it would become my full-time job.

That was very clear, after about a year of doing it at farmer's markets and just kind of continuing the experiment, I was like, I think this is more than an experiment, I think this is something I should probably really give myself over to. Once I did that, it definitely took root and grew into a huge project.

I've written over 40,000 poems with Poem Store. I don't really do it in public anymore because I just kind of got burnt out.

It was a very young person's world to do that in. I had a lot of energy then, and now I'm a little older, and I feel a little more protective of my energy.

In the midst of all of that, that's how I got books published, that's how I met people. It was a really connective way to be part of the community and bring poetry to all types of different people.

Joanna: Wow, 40,000 poems. That's kind of incredible. On that, I mean, this is a very interesting thing, and I think goes to the heart of creativity.

I do know quite a lot of poets, and some poets insist that it takes a very, very long time to be happy with a poem and put it out in the world. You were basically doing a connection, and then a fast creative publishing type process.

How do you connect so deeply and so quickly, and then turn that into creativity in a finished product in a short amount of time? I know you're not doing that anymore, but—

How did you change that mindset of “it must take forever to do a poem” to going so quickly?

Jacqueline: Well, I like to hold both sides of it. I still, even throughout that whole process, wrote books. Those poems did take a lot of time, and craft, and working with an editor.

The painstaking, beautiful longevity of a single poem being on the editing board is something I'm still really familiar with and love a lot. Then I also think there's this freedom in just being able to have this poetic conversation with another person, which is basically what I was doing with Poem Store.

These poems that I would make in the moment, they're very spontaneous. so they're including that person's energy, and there's also a mystery there. Like I wasn't quite sure what I was going to write, and I didn't really know what I did write until I would read them the poem when I was finished.

Just yesterday, I work in a lot of schools now and just visit kids and show them what it's like to be a poet, teach them about poetry, and I brought my typewriter to class yesterday.

There's something really magical that happens when someone has a typewriter, and I think that that was also a big part of it.

There was like this deep lore of how is this person being so vulnerable out here in the world writing poetry, but then also, wow, this machine from the past, this is sort of like a time travel opportunity.

Joanna: I imagine some of those kids have never even seen a typewriter.

Jacqueline: Yes, and there's something about allowing oneself to be free creatively like that. Like those poems had nothing to do with my ego, right? Like, I'll never see them again. I didn't keep copies of them. Every once in a while, I would take photographs of ones that I really loved or something like that.

There was something so special about releasing that sense of control, and the need for perfection, and the need for such a clear certain outcome, that I think is actually really nice to apply to art making.

Although I really do value the craft and the focus and will continue to write books in that way for the rest of my life, I also will always allow myself to slip into that more improvisational sense of writing.

I mean, honestly, even just yesterday, it was a reminder that my imagination is this thing that's always growing and changing, and there's new language to uncover. It feels like a challenge in a playful way.I like, especially as being someone who is a writer for my profession, making any kind of outlet I can for that playfulness in my work.

Joanna: I love that. Well, let's talk about the books of poetry, the collections. I'm also fascinated with this, in that you have to choose poems to go into a collection, which are usually themed in some way. I own quite a lot of these collections of poems.

How do you choose the poems that go into a collection? How do you know when it's finished?

As in, okay, I am happy that this represents whatever that particular point in time is. It seems like quite a nebulous process.

Jacqueline: The choosing is really a fun process. I think, for me, what will happen when I know a book is coming into focus, is I will spend my time reviewing what I've been writing over the last year or two years in my journals, and I'll see a pattern or a theme.

For example, I made a trilogy of books about my time living in California, and each book in the trilogy is about a certain place that I lived.

What allowed me to choose those poems was that I saw this beautiful kind of exploration of place, and I thought, “Oh, I have an entire books worth of poems about my time living in Northern California. Oh, I have an entire books worth of poems about my time living in Los Angeles, and then another for Joshua Tree.”

I could see this theme. So then I went back in and added to it.

I thought about my core memories of those places and patched in what I thought was missing.

With all my books, it's been a similar process of sort of noticing that either there's a theme building up, or there's a collection of poems that are based on place or a certain time in my life. So that's kind of how the choosing happens with this reflection process.

Then there's how to know when a poem is done. I work a lot with clients one-on-one who are trying to create books or trying to polish their poetry.

I always say, you really do need to work with someone else at some point in the process, so that they can say to you, “Yes, this makes sense. This is clear. This is getting across the point you're trying to get across.”

You need to have that reflection of another reader, someone else's eyes on it, to give you the sense of closure that you might need.

Not every poem is like that. Some poems, randomly you'll write something that's just like, “Pow! That is done. That is good. I love it. That's very clear,” but I think that's very rare.

Joanna: I love that. So I also wonder about your poetry, and in fact, your books in general, because you have poems in this book A Year In Practice. I tend to read poetry from a physical book, sometimes I'll get an audio or maybe watch a video of a poet performing, but I'm one of those people who appreciates the physical layout of a poem.

That's often a place where people play with physical layout and the beauty of words on a page, as opposed to the beauty of the words. Do you know what I mean?

How do you incorporate physical beauty in the layout words on the page, or is that less important to you than just the words?

Jacqueline: I do love that. I love when people appreciate that because that is a big part of the craft. Deciding where to break a line, deciding what space goes between which stanza. I think for my work, a lot of times I'll be creating something that the line breaks are giving the pause and the cadence to the poem.

So I'm a huge fan of reading poetry aloud. Like every time I read a book of poems, I will read the poems out loud because I feel like there's a lyrical song-like quality to poetry, there's a rhythm.

The lines, and the way they break, and the way that the words appear on the page offer that. There's spaciousness around certain words.

I think for my work with the typewritten poems, then there's another quality of this kind of tactile, visual expression with the mistakes that I leave in, or just when the typewriter skips a beat, or when I go over a spelling mistake with just a few Xs, because on my typewriter, there's no way to backspace or amend mistakes.

I think that things like that give a different life to poems. Especially, if a poem is just a block on the page as like a narrative or prose narrative—which I do write poems like that a lot—I think it's definitely still an invitation to kind of slow down.

I think that's the difference a lot of times between just straight up prose or narrative fiction or something, is that you get this chance to have space around the words that are usually delivering something very, very macro, very large, as a condensed space, and as few words as possible, honestly.

Joanna: Let's get into A Year In Practice. It's a great book, I really enjoyed it. Of course, people can listen to this whenever because it does have all the seasons in it.

How should we consider the seasons as they relate to a calendar year, specific writing projects, and also times in our lives?

How might they overlay each other?

Jacqueline: When I was creating this book, I looked to the earth for many things. A lot of my life revolves around my connection with the planet. Especially as a creative person, as a writer, as a professional artist, I feel like a lot of times what I'm searching for, what I'm honing in on, is some sort of a methodology that allows me to have a consistent routine.

That changes throughout the seasons of my life, depending on what's happening in my life, what other work I'm doing, where I live, what personal things are happening in my world.

This project started many years ago when I lived in Los Angeles, and in Los Angeles the seasons are very subtle. You have to really be paying close attention to understand that there even are seasons, and what they're telling you is even more subtle.

So I think for a poet, that's actually an incredible invitation because I think subtlety is something that I love to lean into and kind of see what is really under the current of this. What small hints and arrows am I missing if I just kind of rushed through this? Subtlety asks you to look closer and slow down.

So I really learned about the seasons in a new way when I was living in Los Angeles, and this book kind of came out of that. I was like, okay, in the winter, I need to give myself some kind of space to slow down and turn inward a little bit.

Even if you're living somewhere where there isn't snow, or there isn't actual cold weather to deal with that kind of forces you to be in hermit mode, you need to give yourself that because your human body kind of requires that.

There's not a lot of space for that in our society. I did an interview with someone once about the book, and they were like—

“Basically, your book is suggesting that we rest a lot.”

I think that's a big part of the creative practice that can easily get overlooked because we're really concerned with product and outcome. It does feel really good to finish something or to fully indulge in creativity and let yourself be really fervent with whatever your ideas are.

I also think that noticing the season at hand and reeling it in for winter allows you to then move into spring where there is this charge, and there is a charge of energy that you can carefully and slowly approach so that you don't get burned out.

Then you go into summertime, and that's a major time of togetherness. Like that's when we're together, when we're sharing our work, when we're taking in work, but in a group. I imagine always in the summer, it's like when you're allowed to fully be out.

You're not having one foot in the door and one foot out, like you might be in spring. That care then kind of translates into the fall where you start harvesting and gathering again for your winter introversion or for your winter seclusion period. So there's a lot of energy in fall for noting:

What will I need in my creative cave? What can I do for myself now? What can I finish now before I kind of start to turn off a little?

So I love winter, and I feel that winter is a really appropriate time for creative gestation. Then the seasons that follow, there's a lot of choice that's involved.

You made these choices to turn inward and to focus and to kind of calm and take your foot off the pedal a little bit, but then when you come back into action in spring, it isn't like you just then slam on the gas. The truth is, is that winter kind of starts and stops for a long time, and spring is very moody. That really affects our creative practice. It really affects our ability to show up for our ideas that maybe we've been brewing during the wintertime.

Joanna: In the bigger level, I was thinking as I was reading the book, there are different phases of our life. So you mentioned that your Poem Store, you're not doing that anymore, that was like a phase of life that you have now moved on from.

We all have the seasons, that sort of macro level. So for me, for example, the perimenopause years were like a winter, in that I really struggled to do a lot. I needed, or I should have, given myself more grace and more time, but it really felt like a winter.

I've come through that now, and I feel like I'm really in a spring, like a reinvention. That's sort of a number of years over different parts of our lives that sort of mirror, I guess do you find that they do mirror the annual sense?

Jacqueline: Yes, and I really like considering the seasons of our lives. I think the main thesis for this book is just:

How can we remember what the energetic quality of this season is and then apply that during our life whenever we need it?

So sometimes we need a winter, we need to go inward, we need to rest and recuperate. That might happen in the middle of summer. I think it's more of learning this gift of this language that the seasons offer.

The earth is just saying like, “Here, this is what all the other animals and all the other plants are doing right now. You're a part of that, maybe you could consider doing that also.”

Then thinking how that applies to the greater practice of just living and kind of knowing, okay, I've memorized what goes on during this time of year for myself, or I've memorized what it feels like to sort of downshift. How do I apply that?

I've done the work of memorizing it, so it's almost like now I can flip the switch. I can make the choice and say that's the energy I need right now. That doesn't really happen unless we give ourselves over to learning it and practicing it.

That's, I think, why I wanted to have the word “practice” in the title of the book, and to consider practice not just being creative practice and artistic practice, but truly the practice of living and engaging with life in a healthy and beneficial way that might be forgotten very easily, because there's so many things in our daily lives that steer us away from that.

Joanna: So as we're recording this, we're coming into spring. I was telling you before we started recording that the sun is out here in the UK, and it feels like, yay, spring has finally arrived.

I love in the book, you have this poem called “Emergence,” and I actually have on my wall, I have a little card that says, “Trust emergence,” which I feel reminds me that something will emerge. Even if the garden has been bare in the winter, something will start to sprout. So can you talk a bit about that?

Why does the word “emergence” call to you?

How can people understand that that will happen? I think it's really hard, hence why I've got it on my wall to remind myself.

Jacqueline: I think this really does just circle around the theme and the thesis of the book of this remembering, even this concept of emergence and that something will emerge, something new will happen.

How incredible is it to see the flowers and the perennials all pop out of the ground every year? It's never something that I'm not in awe of. It always almost shocks me.

I think there's something in that that's change is the written law of the universe. It will always be happening.

We will always be shifting and growing and changing, something different will always emerge. That's the nature of life.

We forget that. We get stuck in these feelings that nothing will change, that things are the way they are. I think that that's partially just what it is to be human. I think we get caught in our minds. We get caught in a feeling. We get caught in our bodies.

We forget that, yes, like something new will come, and that as it does emerge, the way we respond to it, the way we notice it, the way we meet it, and what we do with it, and the pace that we do all of that with it, really matters.

So I think, again, that memorizing. Well, how do you approach emergence? How do you keep yourself in line with the fact that that will come? What will you do before it does?

I love using the metaphor of the plant world because I think that the plant world is so reliable in this way, where if something emerges too soon from its cave of growth, from its safe underworld below the soil, it might get killed in the frost.

That's what happens every spring, there are these frosts that happen, where winter kind of makes its last stand. If we're not careful, coming out into the world after our moments of inward retreat, we could have that experience as well. We could get a little burned. We could get burnt out.

Some idea that we bring to the surface too soon before we're really ready could then get kind of snuffed out a little bit by the fervent energy of spring, and then things get lost. I think that's kind of what I think of when I think of emergence.

Joanna: You mentioned fervent energy there, which I love, because I feel that is the energy right now as we're talking. Everything's growing, and it's a bit mad out in the flowerbeds.

This is a problem that authors have is that often there are so many ideas. There are some people who struggle to find ideas, but many of us, I'm sure you included, have so many ideas. I don't know which one to focus on. I wondered, since you do so many different creative things, how do you know—

When all these things are springing up and emerging, how do you choose your next project?

Whether it's a collection of poems, or a full-length book, or all the other things you do?

Jacqueline: I'll try to stay in the logical realm with this because, for the most part, I actually think that that's a very intuitive experience. When I choose a project, it's usually because some kind of door opens. There is some pathway that is easeful, and I noticed that.

I think logically and practically what that looks like usually is like, okay, I'm feeling my way into a new project, there's probably a few at once that I've been thinking of, and all winter I've been brewing these ideas.

Then something will happen where I'll say, oh, okay, this is the easy way forward with this, and it's inspiring to me, and it's easeful. So that's the thing I follow. Then sometimes that peters out, and then I turned to the next thing.

So I think having your clear ideas of: what are the things that would make you feel great? What are the things that would inspire you? What are the things that you feel energetically pulled to do? Then also, what ease comes with those things?

Like if you choose a project, and then suddenly the next day, you notice that there's a grant proposal that just opened up that's in the same vein as that project, to me, that's a practical sign to try and put my effort in that direction.

I think following those practical signs is also very much like what the Earth does. When a plant is growing up and out of the soil, it's like, I'm going to lean toward the sun, and I'm going to make this easier on myself. I'm not going to grow in a direction that would make my growing harder. So I think that that's how I focus on things like that.

I let myself intuitively move towards what's easeful.

It's hard enough in the world to make a living in any way, so I think that if your artistic practice is your daily job, then there's a lot that rides on the ease of what you choose.

Joanna: That's interesting. I'm also intuitive. We actually talk about intuition quite a lot on this show, so I'm glad you said that. I do feel when I want to tackle a project, like this is ready now, it does emerge. It comes out. Some books, like one I'm writing at the moment, it's been years in germination—since we're staying with that metaphor.

Let's come on to summer because you use the word “celebration” in the summer section. This is something I, and many authors, struggle with. In fact, someone asked me the other day in an interview, “What's the favorite book you've written?” I was like, “The next book. It's always the next book.” So I wondered, what do you feel about this?

How do we celebrate what we have done, our past, as well as just moving onto the next thing?

Jacqueline: I think that's really interesting. I love the books that I've written.

I feel that there are some books that I've written because they were more of like a prompt. They were more of something that was almost like requested of me, either to continue my career moving forward or just to get something out of my brain that I knew was almost like taking up space.

I think that I don't judge the reasons why I make things, as opposed to just looking back and being like, “This is a good book.” I still feel that way, and I actually feel that way about all of my work.

That doesn't mean I don't have a favorite, but I do feel this sense of letting myself just enjoy the successes I've had, and the fact that I've written eight books and created over 40,000 poems in the world.

I love to feel that actually anything that comes after all of that is just like a cherry on top. I've already done all of this work that I'm really proud of. I kind of let myself live in that way, instead of feeling this push and rush to be more or make more.

I haven't written a bestselling book, but that doesn't make me feel badly about myself. It's more like, well, but I have written eight really great books that I am proud of. So there's something about this comparison that can happen in the world of artistry that I try to steer away from, and just sort of look at the facts.

I actually have in my book Every Day Is a Poem, which is all about cultivating a poetic mindset and the practice of poetry, I talk a lot about reflecting on one's life, and thinking of all of the skills that we have, and all of the things that we have done, and all of our accomplishments, but on a really simple level.

I love to consider all of the experiences that I've had, all the places I've gone, the friendships that I've nurtured, just the simplicity of being like, well, you know, I've enjoyed cutting a cold apple on a really hot day with a beautiful sharp knife. That feels like an accomplishment to me.

So if I'm reflecting, I'm just like, wow, I've done a lot. I've experienced a lot in this life. Instead of thinking that that's exceptional or special, I think that every human could do that. It's just about reframing the way you see your life.

Joanna: I think I always just feel like I have so many ideas and so many books I want to write. It's like once one is done and out in the world, and I've released it, and now it kind of belongs to everyone else, I'm just excited about the next one.

I think I struggle, like many people, with the idea of rest. There's always more to create.

Jacqueline: Yes, and I mean, I feel that way too. I have many projects that I'd like to complete in my lifetime. I think there's something to be said about—and this has definitely helped me—about just practicing patience with all of that.

I've had periods in my life where I have had a book come out every single year. Now for the past few years, that's been a little different.

I think at first, even like downshifting from my experience with Poem Store, which was just constant output, constantly creating and seeing this completed poem go off into the hands of a stranger over and over again, it really sped things up for me.

I think over the last few years, I've been practicing just slowness.

I have the word “SLOW” written in huge letters right above my desk, just reminding me that great masterpieces take a really long time, sometimes a lifetime.

I think the Earth really shows us that also. A Year In Practice is kind of revolving around that same idea of your whole life, and all of the seasons of your life, and what you create, it's all adding up to be this great masterpiece.

It's not just like a book that's published in your hand. It's also just like every moment by the end of your life adds up to be this really incredible artwork. Especially if you approach it that way, especially if you try to practice living your life artfully, then I don't think there really are mistakes to be made.

Joanna: Just coming back to that word “slow” because it's so interesting that you have that. I mean, I've got loads of things written next to my desk on all my little bits of papers and quotes and things. I do not have slow.

I do have, “Create a body of work I'm proud of,” which I think that resonates with what you're saying.

What are some practices that can help us slow down? Particularly in this world, a lot of authors now, we have to be on social media, we have to do things to keep our profile up so that people can find our books because it's pretty noisy out there.

What are your suggestions for slowing down?

Jacqueline: I think there's something in the creative practice that tells me, don't grasp, don't rush. So if I'm working on something, even just a single poem, if I'm working on anything creative, I will check in with myself and be like, am I rushing? Am I grasping at something here?

Or does this feel playful? Does this feel like I'm tending to a deeper emotion? That doesn't mean I won't end up writing really quickly on the page some great burst of inspiration, it just sort of allows me to review where I'm at internally.

I do think that that's probably my greatest advice is just that rushing through anything, it can easily feel like, oh, I'm just following the blaze of inspiration. If you look closer sometimes, if you just review the feeling, you might be like, oh, actually, no, I'm just trying to push through towards an outcome.

I don't think creativity really likes that. I think our imaginations are running rampant all the time, and if we slow down to tap into them, there's a lot there, but I don't think it requires us to be on the same pace as it.

We can grab maybe one piece of that, and then slowly nurture it and take our time with it. As opposed to feeling this sense of, I've got to rush and collect every little idea or image or concept that I have.

I think I heard an interview once with Tom Waits, where he was talking about where he was driving in the car. He would always think the muse is coming to him in these moments where he's like on the highway in his car, and he'd say, “Muse, don't come to me now, I'd have to pull over on the side of the road.”

There's something about that—I might be misquoting it—but there was something about that that really struck me when I was younger. Number one, if I have an idea in the middle of the night, I'm going to turn the light on and write it down in my notebook.

Then I think over the last couple years of practicing slowness, I've thought a lot about just letting poems kind of pass through me and not feeling so pressed to document everything.

That has actually released me from that feeling of pressure. You can have a really brilliant idea, and it can just be a brilliant idea that kind of moves through your body. That's it, and that's how it lives in the world, and it doesn't become something. There's a great freedom in accepting that, I think.

Joanna: In social media there's this sort of thing, if you don't take a picture of it and post it, it doesn't exist, it didn't happen. It's similar. We don't need to share everything. Not everything needs to be documented. So I like that kind of letting go.

Let's come to autumn. In the book, it's so interesting, you do use this phrase, “when the veil is thin.” I use that phrase pretty much in all my novels, in my memoir, as I feel this in certain places, and certain times, spiritual places, different times of year.

What do you mean by the veil being thin? How does it manifest in your work?

Jacqueline: Well, I think specifically in autumn, there's a sensation of being very close to death, because everything is losing its vibrance. All of the green is gone, the leaves are falling, everything is starting to go to sleep. So beyond the veil is winter, is the period of rest, is like the inner cave.

I think that when we're kind of hovering before going fully in there, there might be this opportunity to receive some information.

So I think receiving information in these moments where we feel close to death, or close to our hibernation mode, that maybe our minds are a little bit slower, maybe we're just starting to slow down, and so we're able to receive something on a different level than just this daily grind of like mental reception.

It's actually like, oh, maybe there's something that's a little bit quieter that's talking to you that wants to share information with you. I'm speaking of that in a planetary sense.

Though I also think as the Earth is calming and turning down, and maybe there's a lot of gathering happening, like if you think of all the squirrels preparing for winter, and they're doing this great method of gathering all their food and preparing, there's a sense of us doing that also.

I think as artists, and just as people, we're preparing for this inward turn that comes with that time of year. If we allow ourselves to look at that, there might be this great information download that happens then.

I think when I'm thinking of the veil being thin, I'm thinking of that quietness and that chance for this sort of exploration of something a little more spiritual or unseen that we don't necessarily have time for or that we overlook in other moments of the year.

Joanna: Have you experienced that in any particular places?

Jacqueline: Yes. As I said, I'm an ecstatic Earth worshipper. So for me, all of that information usually comes from being in places that are less populated by humans, or being in the forest, or even just being in the park.

I think being in the natural world and having that chance to downshift into that quietness, I think that is when I typically will receive either intuitive information or my imagination kind of comes into a different play.

I've had a lot of spiritual experiences, and I think the veil can be thin no matter what the time of year is. I just think that sometimes in the fall, it's a little bit more potent.

Joanna: Of course, with the various festivals that happen, Day of the Dead, it is a time of year when that is really focused on a lot more, this acknowledgement of death and the closeness of this other world that perhaps we don't live in every day, and certainly don't think about in the spring when we're just running around in the sun.

Jacqueline: Absolutely.

Joanna: So what's next for you? You have all these different things. You've got the various poetry collections and books.

What will you focus on next?

Jacqueline: Well, I have a book of poems that's finished that I'm just kind of trying to figure out who the publisher will be. So I'll probably start putting my energy into that. I'm really excited about that book. Then I have another idea for a book.

I'm about to move into this house that my husband and I have been restoring for the last few years. That will be a big shift in my life. I'll have a new studio space, and that always gives a lot of creative information. So I'm definitely gearing up for that.

Joanna: Oh, yes, moving house. That's a big one, isn't it? That really does change the energy.

Jacqueline: Yes, a new season for sure. A definite new season of my life. I'm about to turn 40. In November, I'll be 40. So there's a lot of big changes happening.

I always know that creatively, for me, space has a lot to do with what I create. That means like mental space, physical space. I think that I'm looking forward to that next chapter of having just a more grounded space and being able to settle into my home that I'll live in for the foreseeable future.

Joanna: Where can people find you and your books online?

Jacqueline: I have a website, JacquelineSuskin.com. I also have a Substack, if you look my name up on Substack. I do a lot of writing on there.

I'm on Instagram. @JSuskin is my Instagram. I try to keep all those things updated and put out a newsletter every month. So that's a good way to find me.

My books are anywhere you want to find a book, you can find my books for the most part.

Joanna: Great. Well, thanks so much for your time, Jacqueline. That was really interesting.

Jacqueline: Thanks for having me.

The post The Seasons Of Writing With Jacqueline Suskin first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Visit Podcast Website

Visit Podcast Website RSS Podcast Feed

RSS Podcast Feed Subscribe

Subscribe

Add to MyCast

Add to MyCast