Sangam Lit

Kalithogai 108 – A war of words

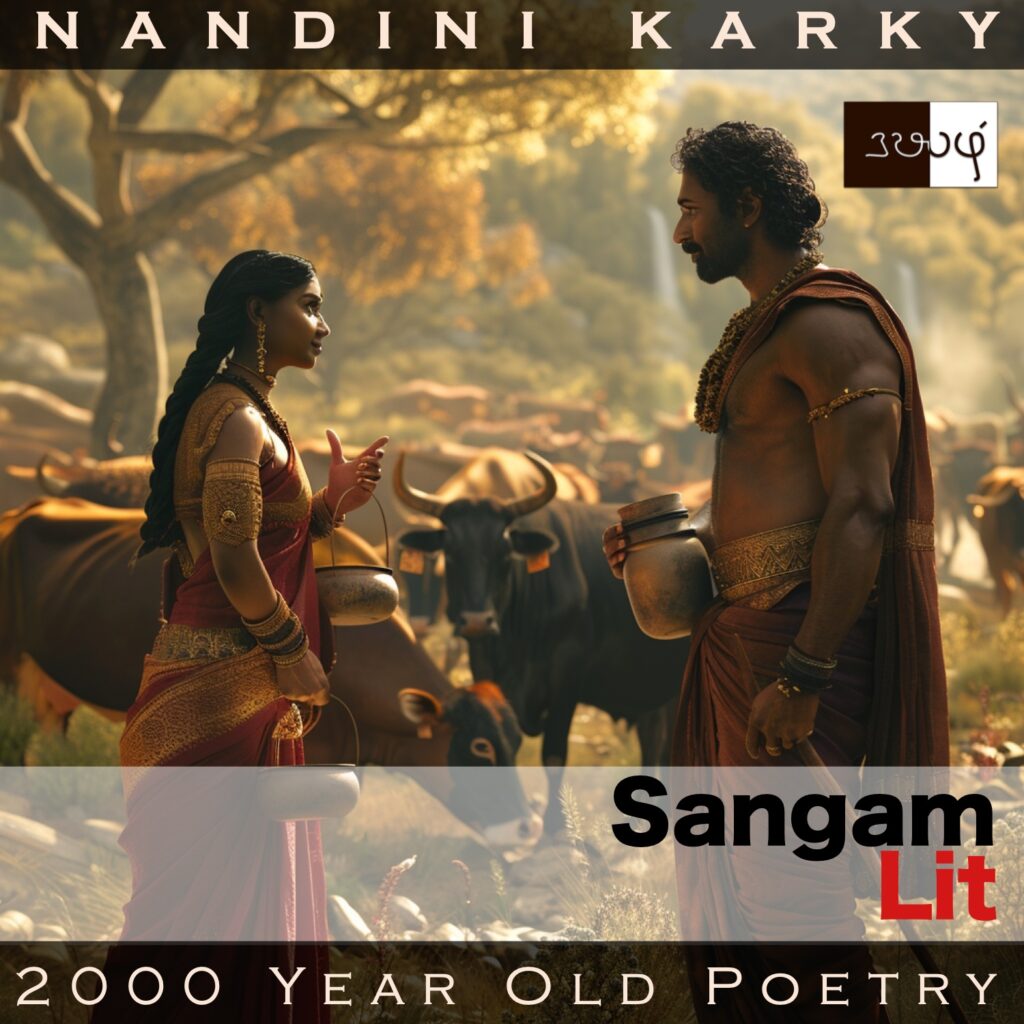

In this episode, we see sparks fly in a couple’s conversation, as conveyed in Sangam Literary work, Kalithogai 108, penned by Chozhan Nalluruthiran. The verse is situated in the ‘Mullai’ or ‘Forest Landscape’ and reveals interesting perspectives about work in ancient times.

தலைவன்

இகல் வேந்தன் சேனை இறுத்த வாய் போல

அகல் அல்குல், தோள், கண், என மூவழிப் பெருகி,

நுதல், அடி, நுசுப்பு, என மூவழிச் சிறுகி,

கவலையால் காமனும் படை விடு வனப்பினோடு,

அகலாங்கண் அளை மாறி, அலமந்து, பெயருங்கால்,

‘நகை வல்லேன் யான்’ என்று என் உயிரோடு படை தொட்ட

இகலாட்டி! நின்னை எவன் பிழைத்தேன், எல்லா! யான்?

தலைவி

அஃது அவலம் அன்று மன

ஆயர் எமர் ஆனால், ஆய்த்தியேம் யாம் மிக

காயாம்பூங் கண்ணிக் கருந் துவர் ஆடையை

மேயும் நிரை முன்னர்க் கோல் ஊன்றி நின்றாய், ஓர்

ஆயனை அல்லை; பிறவோ அமரருள்

ஞாயிற்றுப் புத்தேள் மகன்?

தலைவன்

அதனால் வாய்வாளேன்:

‘முல்லை முகையும் முருந்தும் நிரைத்தன்ன

பல்லும் பணைத் தோளும், பேர் அமர் உண்கண்ணும்,

நல்லேன் யான்’ என்று, நலத்தகை நம்பிய

சொல்லாட்டி! நின்னொடு சொல் ஆற்றுகிற்பார் யார்?

தலைவி

சொல்லாதி!

தலைவன்

நின்னைத் தகைத்தனென்!

தலைவி

………………………….. அல்லல் காண்மன்!

மண்டாத கூறி, மழ குழக்கு ஆகின்றே,

கண்ட பொழுதே கடவரைப் போல, நீ

பண்டம் வினாய படிற்றால் தொடீஇய, நிற்

கொண்டது எவன் எல்லா! யான்?

தலைவன்

கொண்டது:

அளை மாறிப் பெயர்தருவாய், அறிதியோ? அஞ் ஞான்று,

தளவ மலர் ததைந்தது ஓர் கானச் சிற்றாற்று அயல்,

இள மாங்காய் போழ்ந்தன்ன கண்ணினால், என் நெஞ்சம்

களமாக் கொண்டு ஆண்டாய்; ஓர் கள்வியை அல்லையோ?

தலைவி

நின் நெஞ்சம் களமாக்கொண்டு யாம் ஆள, எமக்கு எவன் எளிதாகும்?

புனத்துளான் என்னைக்குப் புகா உய்த்துக் கொடுப்பதோ?

இனத்துளான் எந்தைக்குக் கலத்தொடு செல்வதோ?

தினைக் காலுள் யாய் விட்ட கன்று மேய்க்கிற்பதோ?

தலைவன்

அனைத்து ஆக

வெண்ணெய்த் தெழி கேட்கும் அண்மையால், சேய்த்து அன்றி,

அண்ணணித்து ஊர் ஆயின், நண்பகல் போழ்து ஆயின்,

கண் நோக்கு ஒழிக்கும் கவின் பெறு பெண் நீர்மை

மயில் எருத்து வண்ணத்து மாயோய்! மற்று இன்ன

வெயிலொடு எவன் விரைந்து சேறி? உதுக்காண்:

பிடி துஞ்சு அன்ன அறை மேல, நுங்கின்

தடி கண் புரையும் குறுஞ் சுனை ஆடி,

பனிப் பூந் தளவொடு முல்லை பறித்து,

தனி காயாந் தண் பொழில், எம்மொடு வைகி,

பனிப் படச் செல்வாய், நும் ஊர்க்கு

தலைவி

இனிச் செல்வேம் யாம்

மா மருண்டன்ன மழைக் கண் சிற்றாய்த்தியர்

நீ மருட்டும் சொற்கண் மருள்வார்க்கு உரை அவை:

ஆ முனியா ஏறு போல், வைகல் பதின்மரைக்

காமுற்றுச் செல்வாய்; ஓர் கட்குத்திக் கள்வனை;

நீ எவன் செய்தி பிறர்க்கு?

யாம் எவன் செய்தும் நினக்கு?

தலைவன்

கொலை உண்கண், கூர் எயிற்று, கொய் தளிர் மேனி,

இனை வனப்பின் மாயோய்! நின்னின் சிறந்தார்

நில உலகத்து இன்மை தெளி; நீ வருதி;

மலையொடு மார்பு அமைந்த செல்வன் அடியைத்

தலையினால் தொட்டு உற்றேன் சூள்

தலைவி

ஆங்கு உணரார் நேர்ப; அது பொய்ப்பாய் நீ; ஆயின்

தேம் கொள் பொருப்பன் சிறுகுடி எம் ஆயர்

வேந்து ஊட்டு அரவத்து, நின் பெண்டிர் காணாமை,

காஞ்சித் தாது உக்கன்ன தாது எரு மன்றத்துத்

தூங்கும் குரவையுள் நின் பெண்டிர் கேளாமை,

ஆம்பற் குழலால் பயிர் பயிர் எம் படப்பைக்

காஞ்சிக்கீழ்ச் செய்தேம் குறி

Finally, we have bid farewell to the bull taming arena, and now, find ourselves taking in the lush spaces of the forest domain. The words can be translated as follows:

“Man

Akin to a great king’s army that has laid siege, with your wide loins, arms and eyes that are expansive and forehead, feet and waist that are slender, possessing a beauty that makes even the God of love aim his arrows at you, after selling curd in those far away places, as you move bewitchingly, when you walk on, as if saying, ‘I can kill with my smile’, you seem to shower weapons on my very life, O hostile maiden! What wrong did I do to you, my dear?

Lady

What’s wrong in selling curd? My people are herders and I’m a herder woman; As for you, you stand there, leaning on a stick in front of a grazing herd, wearing a dark red attire and a garland of ironwood flowers. But I don’t think you are a herder man! Could you be the godly son of the sun from the heavens?

Man

That is why I stand speechless! O maiden, who believes in the greatness of her beauty saying, ‘Having teeth like jasmine buds and palm sprouts neatly placed, bamboo-like arms, wide kohl-streaked eyes, beautiful, I am!’, you are so skilled in words, who can even talk to you?

Lady

So, don’t talk!

Man

I shall block you from leaving!

Lady

Behold my sorry state! Blabbering words like a child, you are throwing a tantrum, and akin to a creditor, who sees one of the debtors and asks questions about all the things they are carrying, so that they can seize them, you are speaking to me. What is that I have taken from you? Tell me please.

Man

Don’t you know what you have taken? One day, when returning after selling curd, near a small, wild stream, surrounded by pink jasmine flowers, with your eyes, akin to split tender mangoes, you stole away my heart! Aren’t you that thieving maiden?

Lady

What would I gain by stealing your heart and reigning over it? Will it carry food to my brother working in the field? Will it carry a vessel to my father who’s herding? Or will it hold the calf that mother let out amidst the millet stubble and take it grazing?

Man

Yes! It can do it all that! O dark-skinned maiden, in the hue of a peacock’s neck, with an arresting feminine nature that prevents others from looking at anything else! You live in a village not far but so close that one can hear their churning of buttermilk here. It’s noon now. Why do you have to hurry there in this hot sun? Look over there! There’s a rock in the shape of a sleeping elephant, with a small cascade, akin to juice gushing out of a palm fruit. After playing in the waterfall, plucking cool pink jasmine flowers and resting with me in the moist shade of the ironwood tree, you can go by evening to your village!

Lady

Is that all? I will leave now. To those young herder girls, with rain-like eyes, with a gaze of startled deer, who will melt for your seducing words, go on and say all this! You are one, who goes after ten women a day, akin to a stud bull! You are like a thief, who steals from someone even when they have their eyes wide open! What good have you done for others? And what must I do for you?

Man

With killer, kohl-streaked eyes, sharp teeth, tender sprout like skin, you are so beautiful, O dark-skinned maiden! Know that there’s no one better than you in this wide world! Please trust and come near me. Touching the feet of the Great One with a mountain-like chest with my head, I will swear an oath!

Lady

Only those who know not about you will come with you; You are sure to falsify that oath; However, I have decided to tryst with you. Such that your other women, in the middle of the uproarious celebrations of the herders in our little village, praising the victory of the King, who rules over the honey-filled mountains, don’t see you, and such that your other women, who are doing the ‘Kuravai’ dance in the town centre, filled with dust of cow dung, akin to the pollen of the Portia tree, don’t hear you, come on then, to the spot below the Portia tree in my village, softly playing the ‘aambal’ flute!”

Let’s explore the nuances. In all the Sangam ‘Aham’ songs we have seen thus far, there was one memorable exception recently, a conversation between a hunchback and a dwarf. This verse too lies in that exceptional context of love between workers or the supporting characters. These words are exchanged by a curd-selling lady and a herder man.

The scene begins with the man talking to this lady, remarking about how she seems to be returning after selling curd and milk in faraway places, and mentioning that she seems to be killing him with her perfect beauty. The lady catches hold of his statement about her selling curd, thinking he’s mocking her working role and replies to him saying there’s nothing wrong in selling curd, because I come from a family of cowherds. She adds, ‘You are standing there, in front of a grazing herd, leaning on a stick, but you do not seem like an ordinary herder man. Are the son of the sun himself?’, in a mocking tone. ‘Yes, you are right, that’s why I don’t have the words to speak to you’, he says, and adds that no one can win that lady in the war of words.

The lady gives him a word punch with ‘So, don’t talk!’ and prepares to leave. The man blocks her from doing so. She wonders what she has gotten herself into and comments on the man’s behaviour, equating him to a stubborn child and a creditor who asks a debtor many questions about what he’s carrying so that he may recover his loan, and she connects by asking the man what she has taken from him. To this, the man replies that one day, when returning from selling curd, she stole his heart near a little stream, implying their prior relationship. The lady answers this by asking what use is his heart wondering whether it can carry food to her brother, working in the fields, or go give a vessel to her father, herding cattle, or take the calf mother sent out, grazing amidst the millet stubble, conveying to us, all the tasks that she does for her family, in addition to selling curd.

The man responds with ‘Sure, but forget all that and answer me this. Your village is so close that I can hear them churning the buttermilk right here. It’s noon and so hot! Why don’t we go play in the little cascade nearby, pluck some flowers and rest in the shade of the tree. Then, you can go home in the evening’. Brimming with ideas, our boy here! The lady responds saying, other naive herder girls may fall for these words, but not her, making us understand that she is mad at him, because she suspects that he has been with other maiden. In fact, she calls him a mating bull, which never tires of the cows, for he seems to want ten women a day. Fireworks in her eyes, no doubt! To this, the man replies, ‘Don’t you think that way! There’s no one like you. I’ll swear on the God with a mountain-like chest!’. The lady responds saying ‘Truly only foolish people will trust in your words. You are sure to lie’. But at this moment, she seems to have a change of heart and tells him that she has decided to tryst with him, and mentions a spot near a Portia tree in her village, and asks him to come playing softly on a flute, making sure his other maiden don’t hear or see him, amidst their Kuravai dance and celebration of their king, revealing once again her suspicions about the man’s courting other maiden. An interesting conversation that sheds subtle light on this woman of the past and the pride she took in her work of selling curd and helping her family. A hurrah for this ancient ancestor, who seems to have lived life, not pining for a man but going about and doing her work with independence and confidence!

Visit Podcast Website

Visit Podcast Website RSS Podcast Feed

RSS Podcast Feed Subscribe

Subscribe

Add to MyCast

Add to MyCast