My Dear Alice

Chapter 10: Conclusions

.elementor-heading-title{padding:0;margin:0;line-height:1}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title[class*=elementor-size-]>a{color:inherit;font-size:inherit;line-height:inherit}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-small{font-size:15px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-medium{font-size:19px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-large{font-size:29px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-xl{font-size:39px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-xxl{font-size:59px}

Chapter 10: Conclusions

(a rollercoaster ride of highs & lows)

Image attributions: (HRT) Historic Richmond Town archive; (AAH) Alice Austen House Museum collection.

1894 Effie Emmons Alexander (middle) and Lou Alexander Richards (right)

with Julia Marsh Lord. Austen’s married with children friends. (HRT)

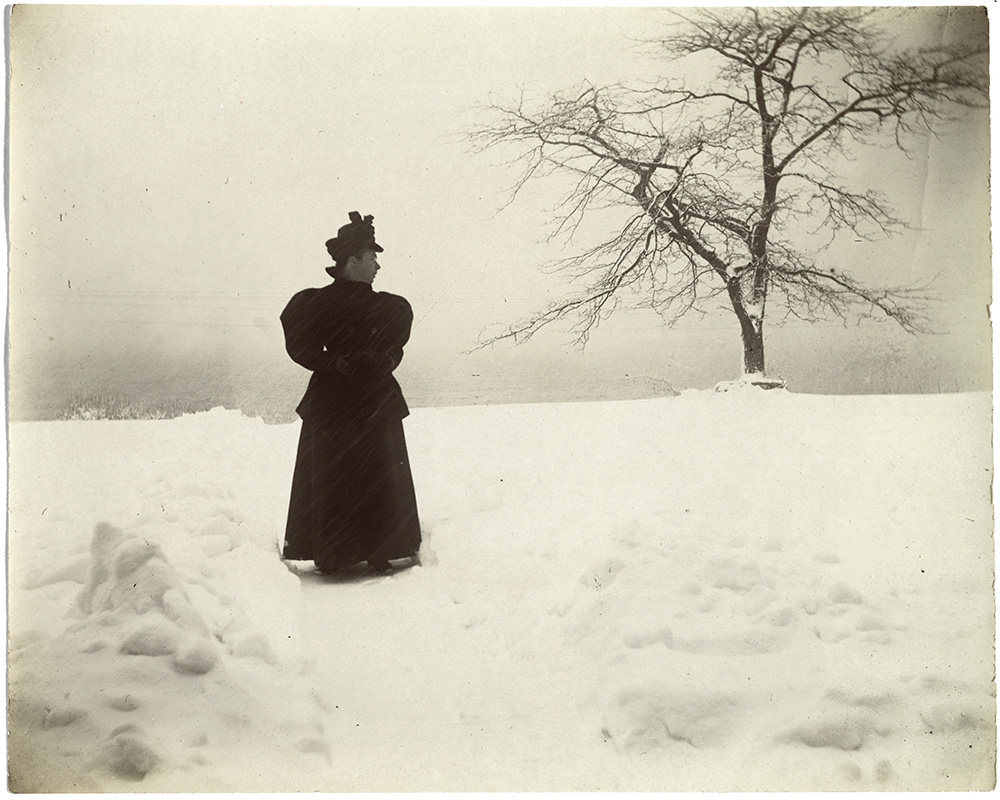

c 1896 Violet Ward in a blizzard at Clear Comfort

while she and Alice Austen spent much time together. (HRT)

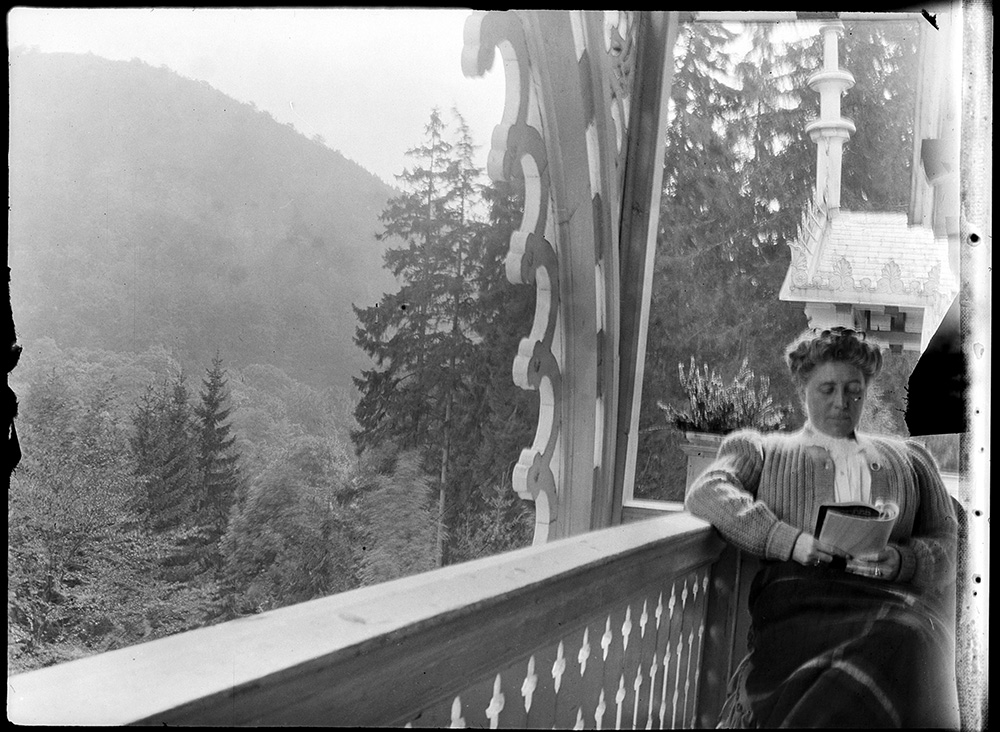

c 1910 Auntie Min in her upstairs quarters

Minnie Austen Hicks Muller at Clear Comfort (AAH)

1903 Alice and Gertrude Tate in Scotland

Their first trip abroad. (HRT)

1903 Alice rows for Gertrude Tate

In Trossachs, Scotland. (HRT)

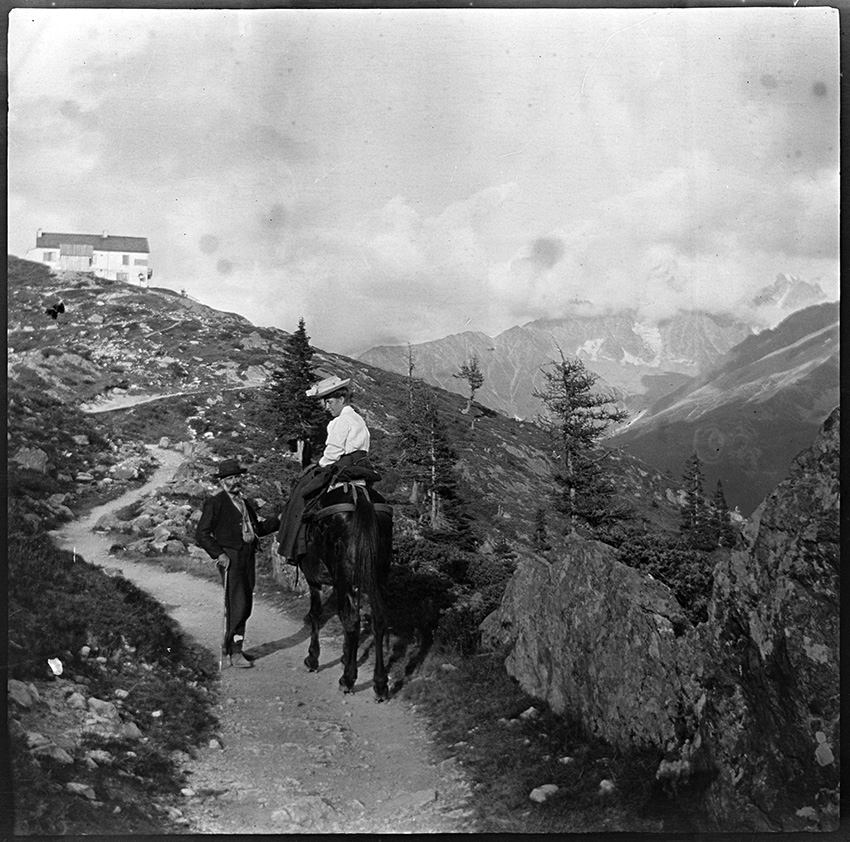

1903 Gertrude Tate on donkey

during 3 months when they traveled to England, France, Scotland, Germany, and Holland.

April 1904 envelope from White Plains

from Julia Martin at the Bloomingdale Hospital for the Insane (AAH)

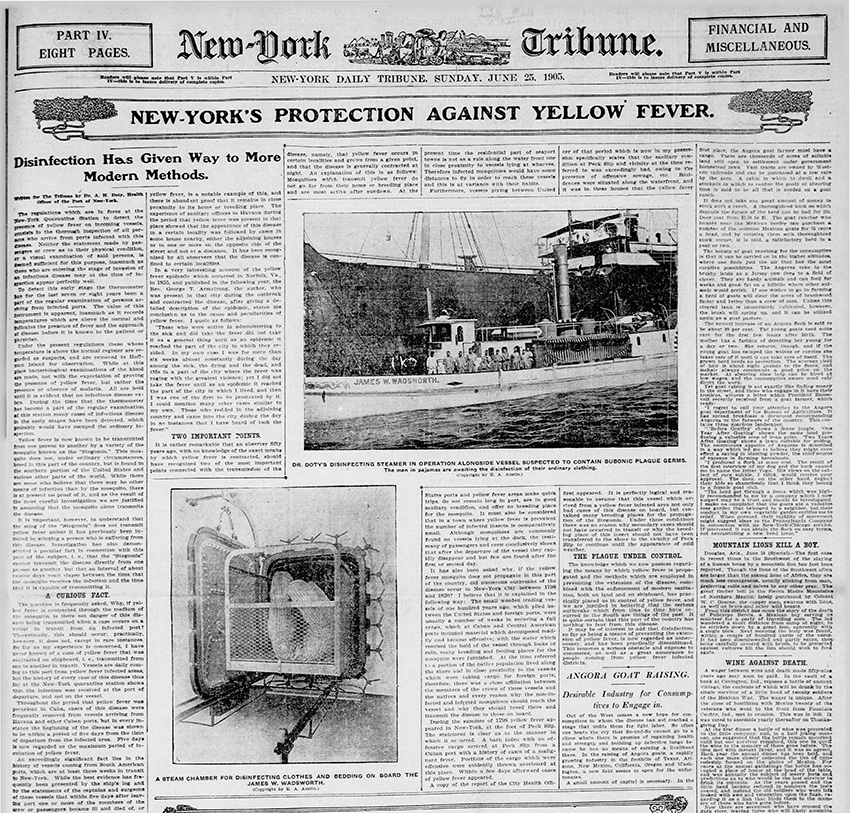

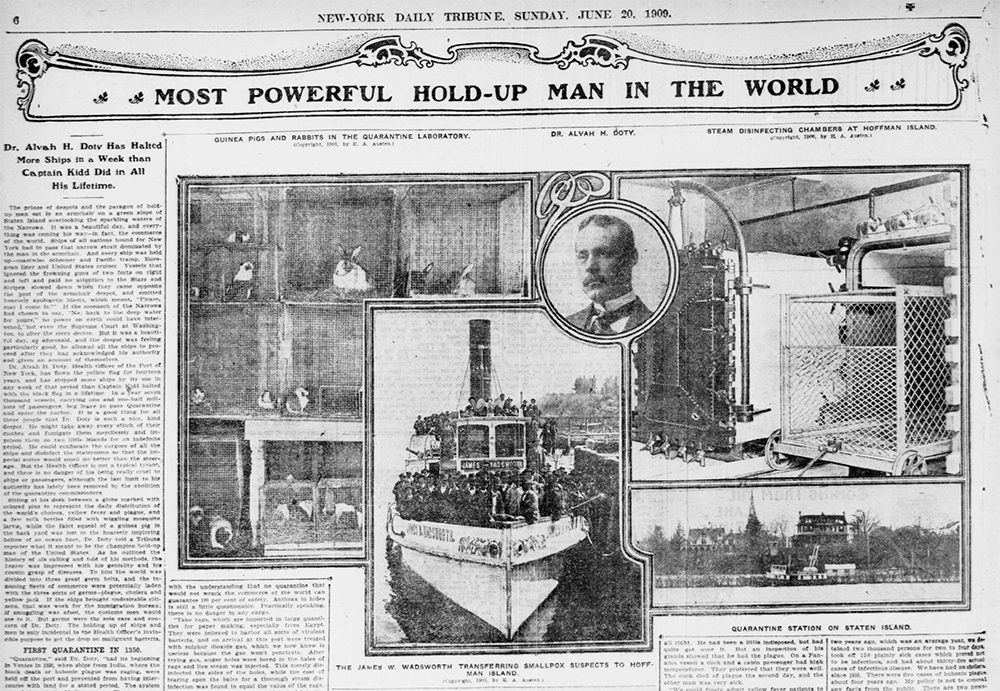

June 1905 quarantine photos for Dr. Alvah Doty

New York’s Health Officer. New York Tribune.

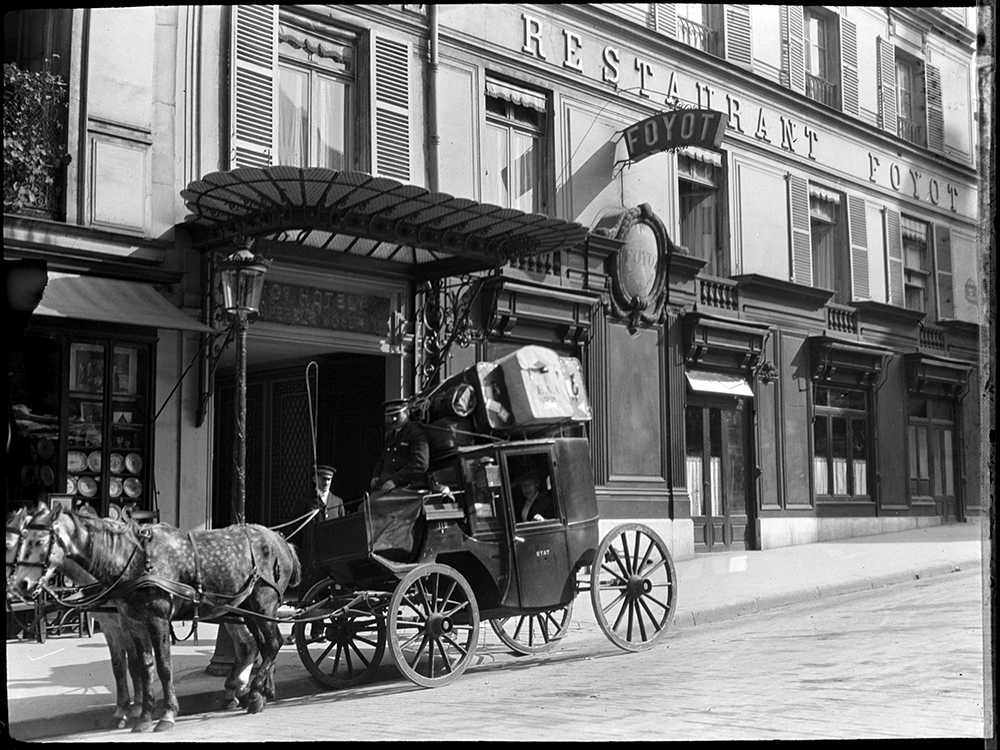

1905 Gertrude Tate in Paris

Trunk reading EAA (Alice’s initials), door reading ETAT, Tate spelled backwards. (HRT)

1905 Beauvais, France

Alice and Gertrude at morning tea (HRT)

1905 Gertrude Tate & another traveler in France

An early snapshot-type photograph. (HRT)

1905 dance class with Gertrude Tate

Tate in back at right (HRT)

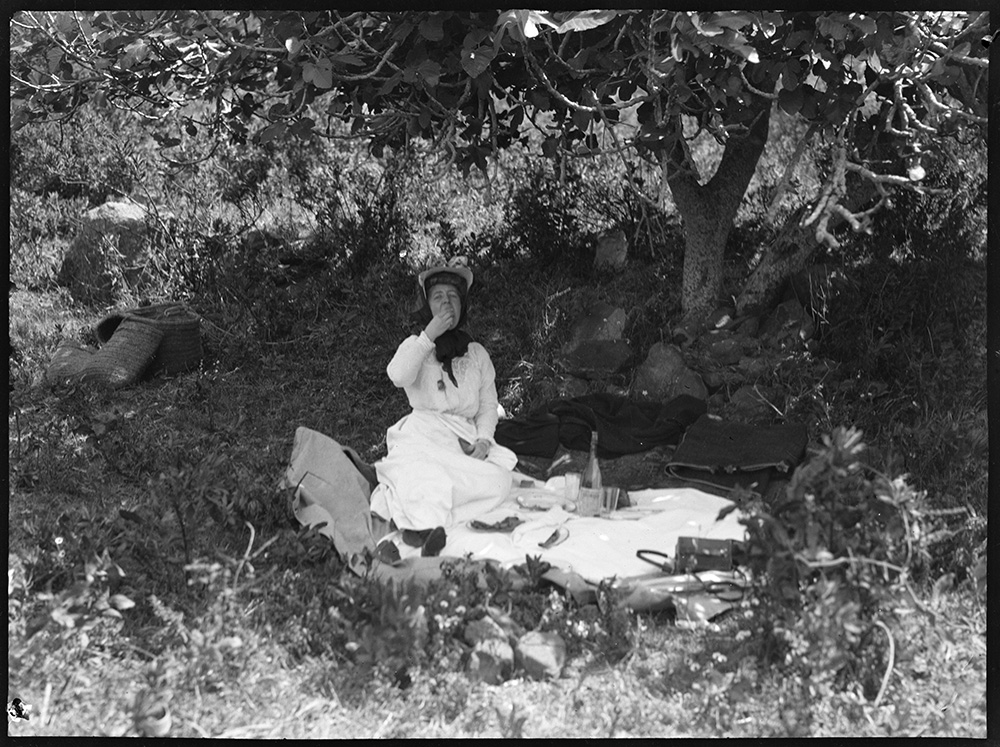

1909 Gertrude Tate in Morocco

at a picnic spread in Tangier. (HRT)

1909 photos by Alice Austen

for Dr. Alvah Doty, New York’s Health Officer. New York Tribune.

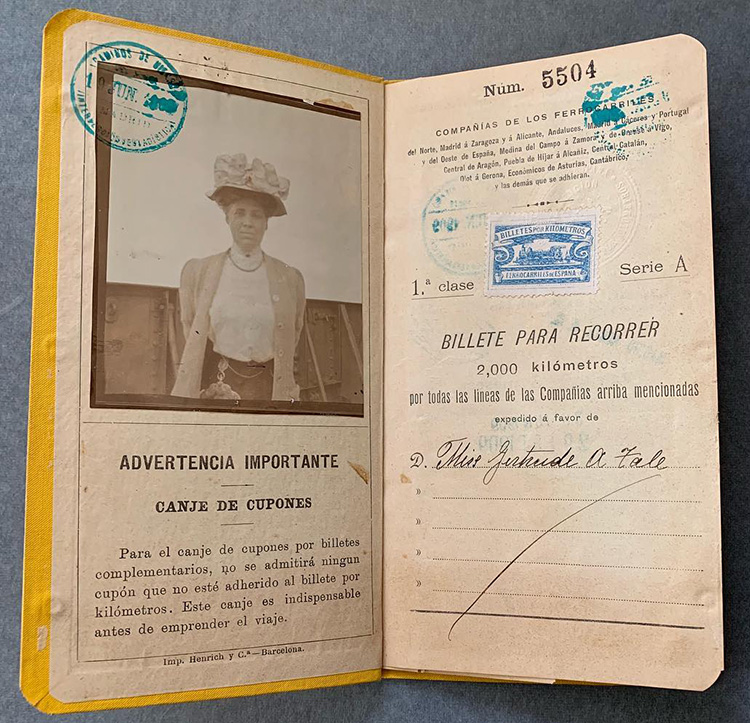

1909 Gertrude Tate’s passport

photographed en route in Spain (AAH)

1909 sheep alongside canal in Bruges

one of many copyrighted photos from 1909 (AAH)

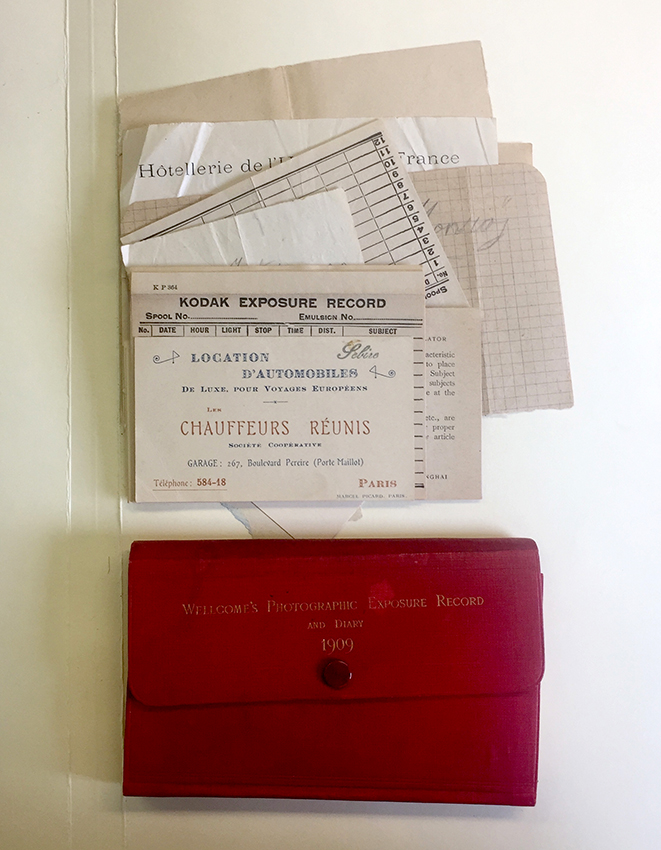

1909 photo ledger & scrapbook items

from a 5 month European excursion (HRT)

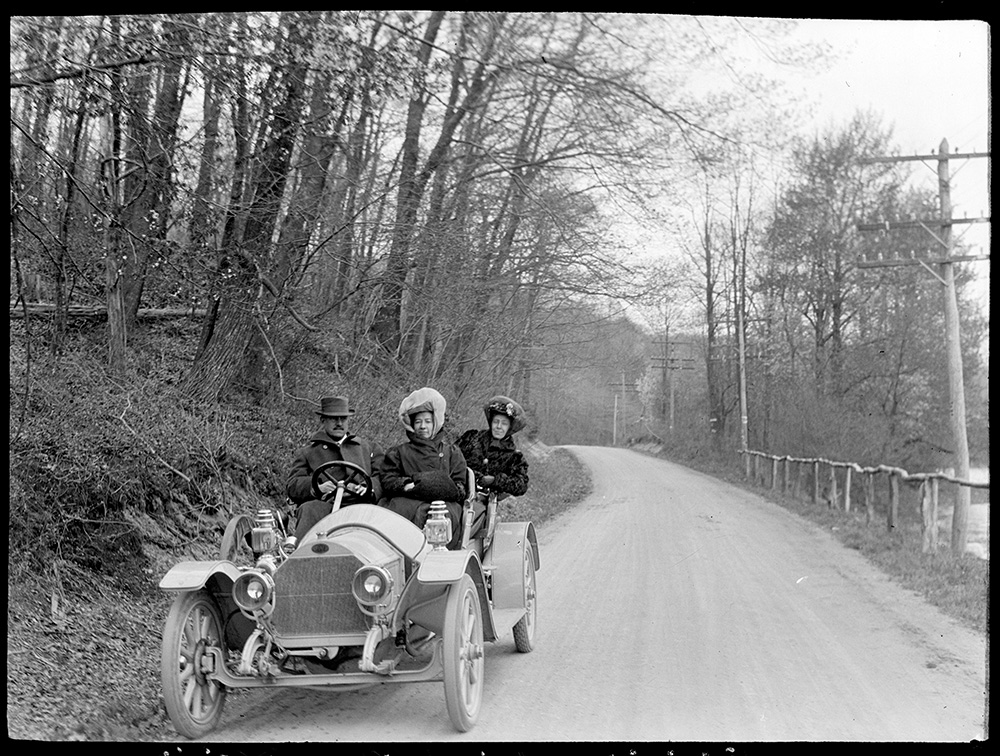

1910 Alice & Gertrude with Guy Loomis

Tate’s longtime Brooklyn friend, sometimes traveling to Europe together – with his car. (HRT)

c 1909 Alice, Gertrude & Guy Loomis

Austen photographing a car race (HRT)

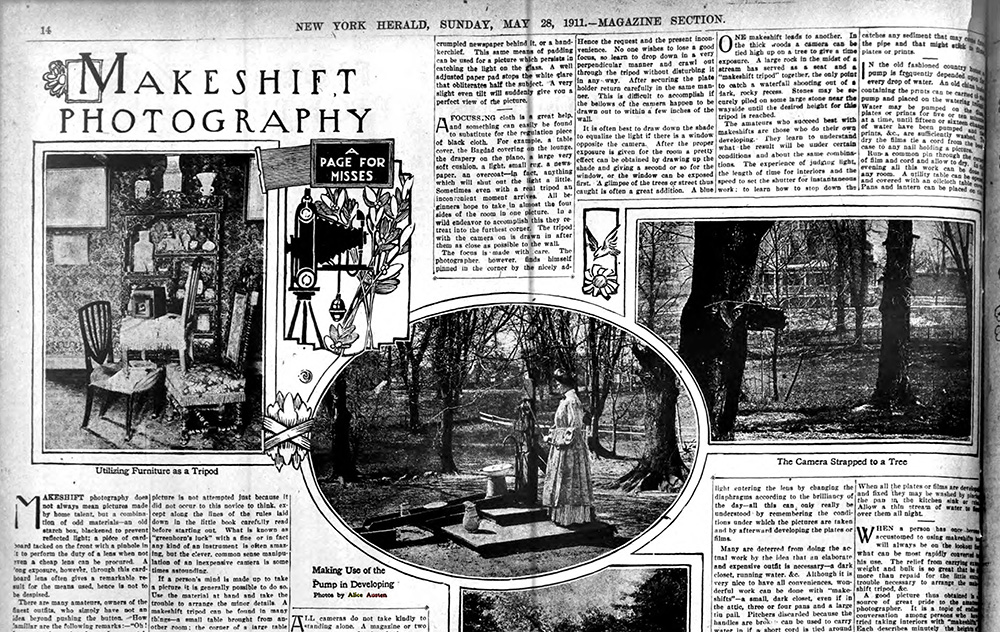

1911 Austen photos in syndicated feature

Makeshift photography article – a Page for Misses.

1911 tree as tripod

for newspaper photo spread – Makeshift Photography.

c 1911 Gertrude & Alice in Italy

at the Hotel Eden Molaro, on the Island of Capri.

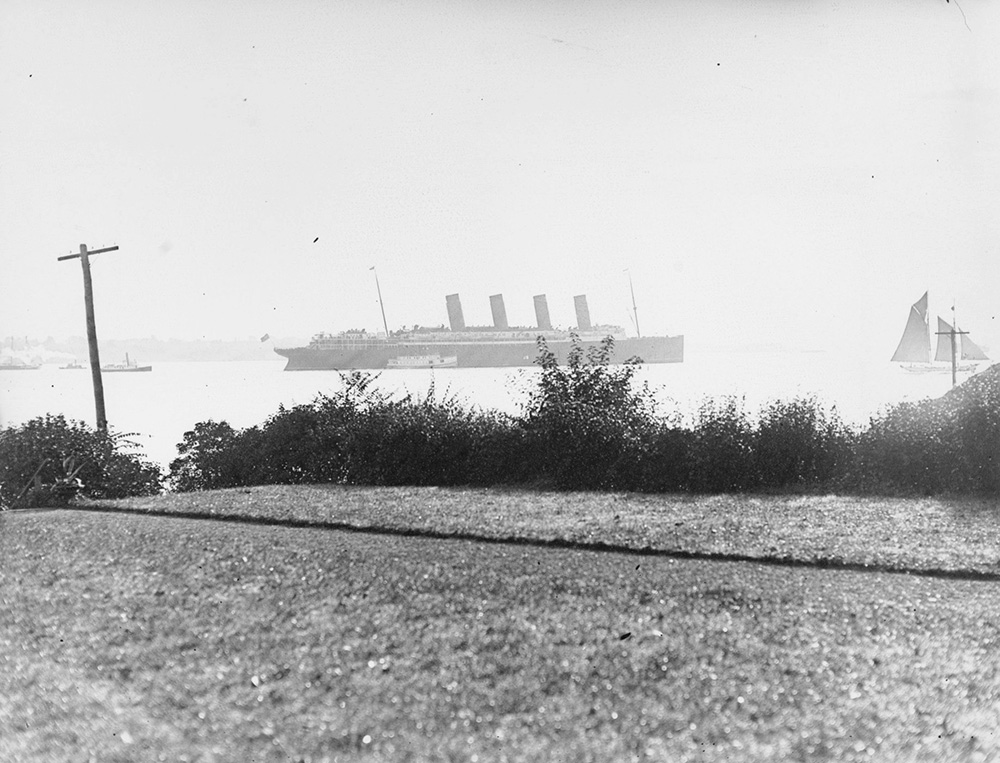

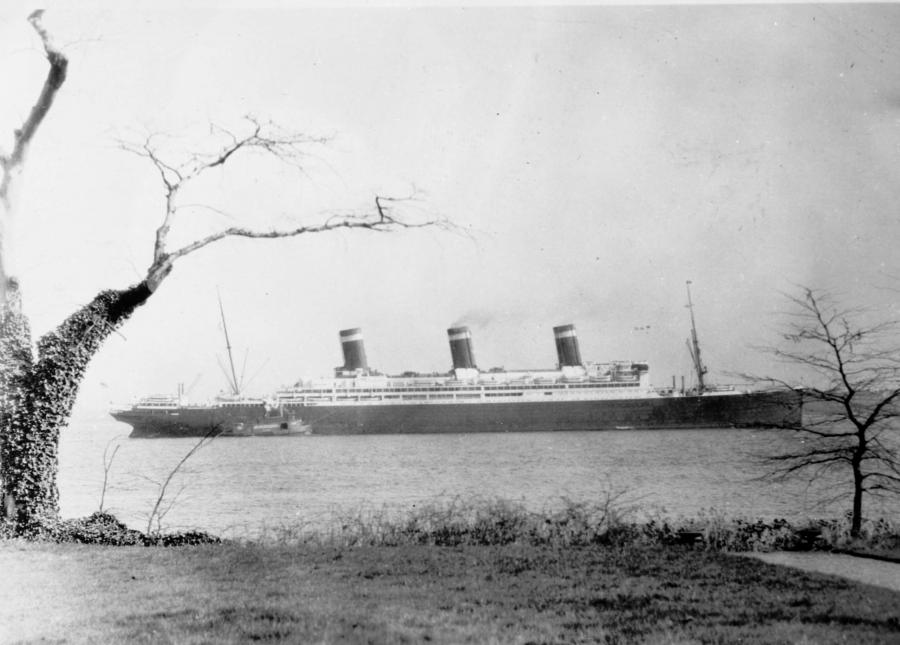

1911 the Lusitania on its ill-fated last voyage

as noted on Austen’s negative sleeve (HRT)

c 1910 Gertrude Tate

at Clear Comfort’s front pathway (HRT)

1912 Austen’s photos in syndicated feature

Illustrations including of Clear Comfort’s front lawn.

1912 The Winter Garden Club for Girls

detail showing photo credit.

1912 Gertrude Tate in Germany

Alice & Gertrude traveled to Sweden, Denmark & Germany in 1912 (HRT)

1912 Alice Austen self-portrait on the SS Cleveland

Returning to America from Cherbourg, France. (HRT)

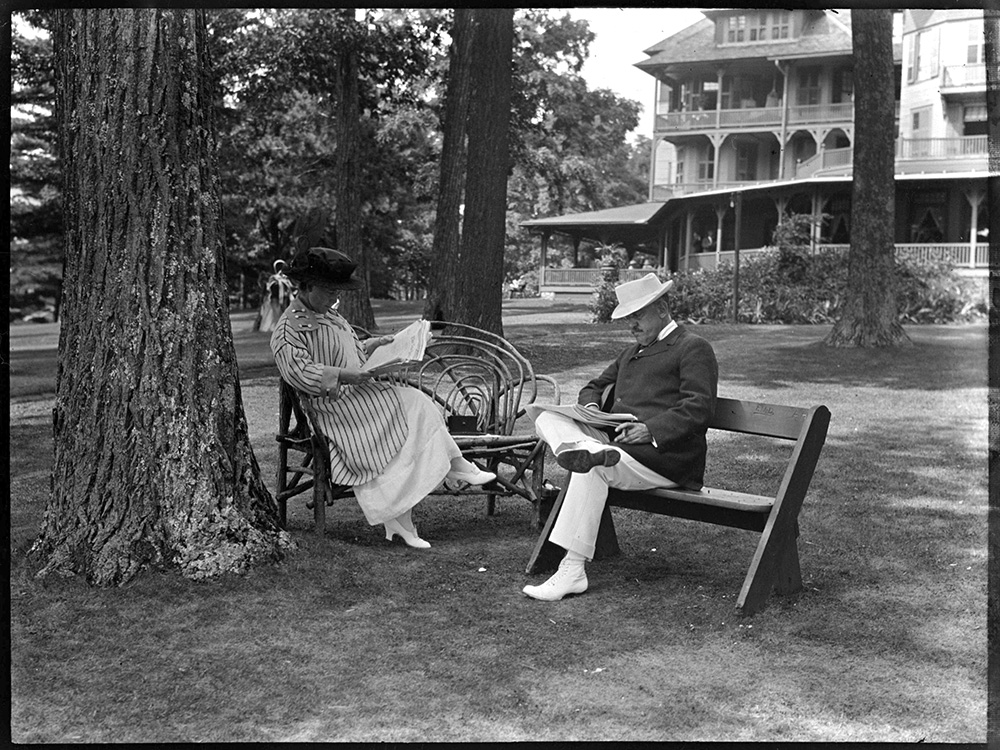

1913 Gertrude Tate & Guy Loomis at Lake George

at the Hotel Sagamore in August. (HRT)

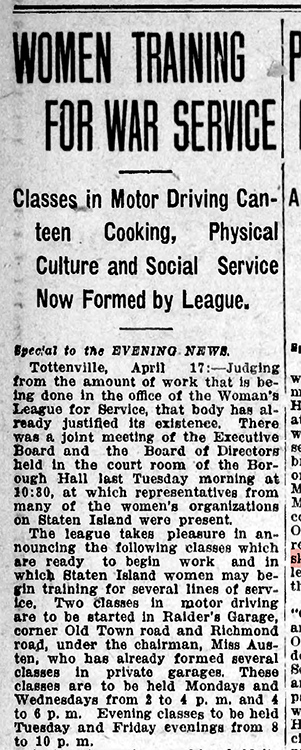

1917 ambulance driving lessons

Austen taught 100s of women how to drive during WW1.

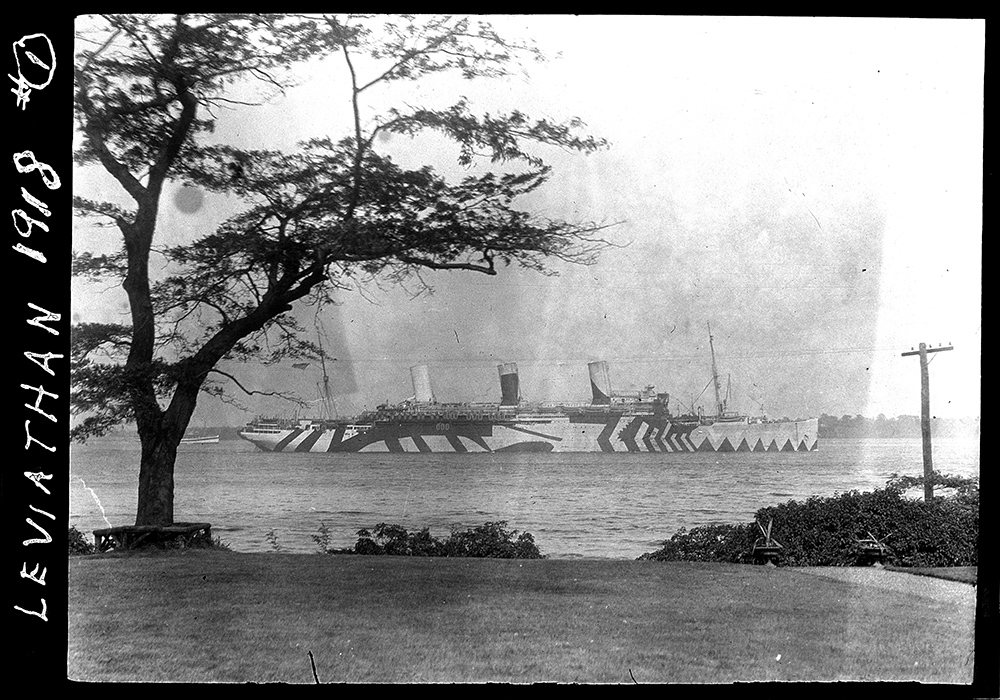

1918 SS Leviathan in dazzle camouflage

Returning after delivering thousands of American soldiers. (HRT)

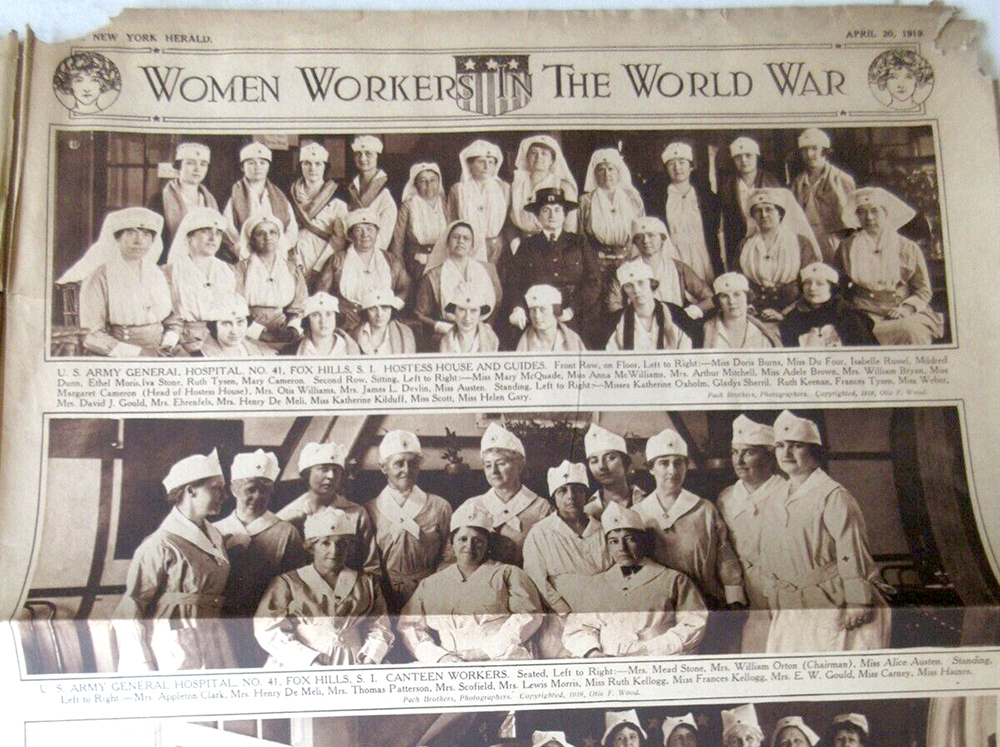

1919 Austen WW1 work

Alice Austen pictured at far right, middle row, in top photo; far right, front row in bottom photo.

c 1928 Gertrude Tate waves flag

at passing ships (HRT)

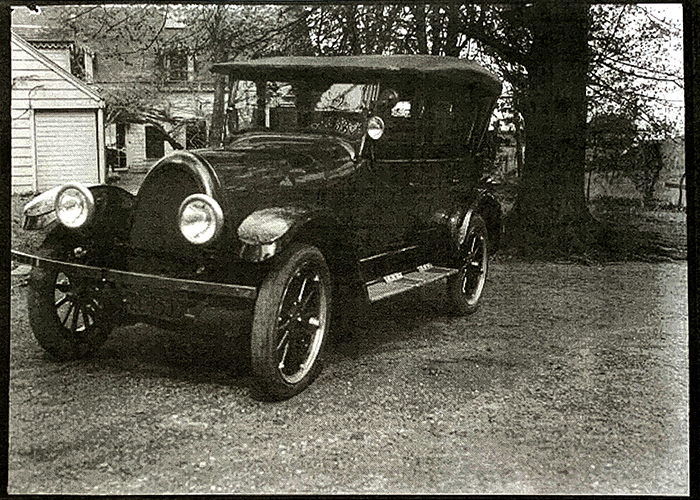

1922 Austen’s new Franklin car

pictured alongside Clear Comfort (HRT)

1920 Gertrude Tate & friends wave at SS Pocahontas

Returning the remains of 2,000 soldiers. (HRT)

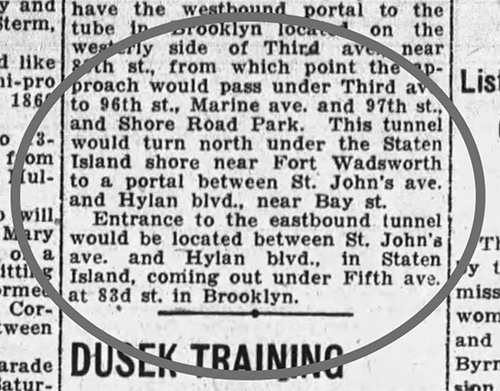

1930 potential transportation tunnel

(see podcast transcript or notes)

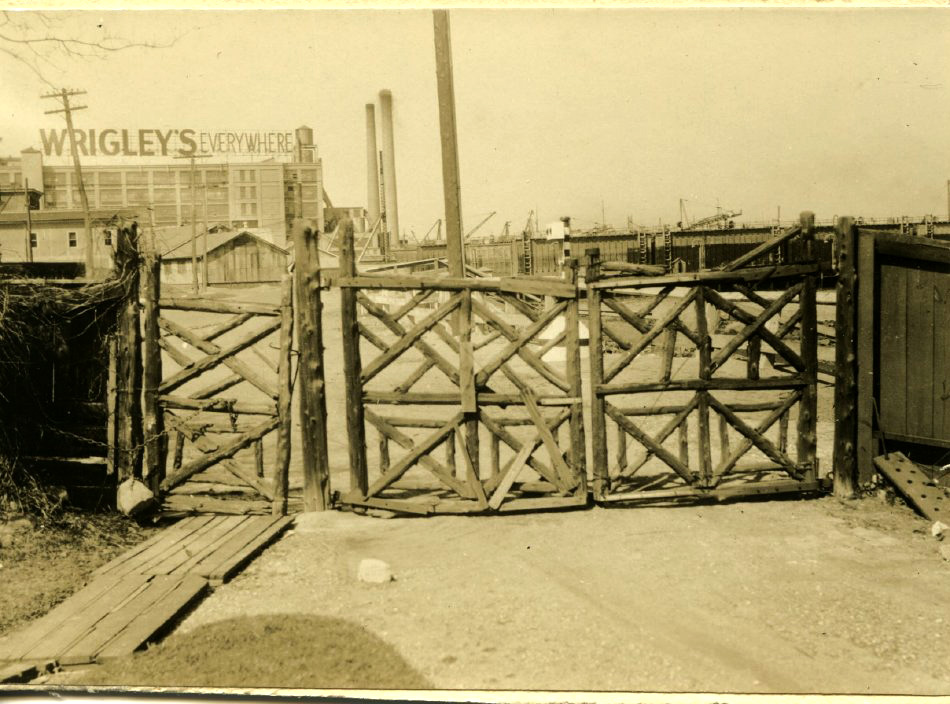

1887 Clear Comfort’s view at rustic gate

entrance facing north (AAH)

1930 Clear Comfort’s view at rustic gate

showing encroaching industry (AAH)

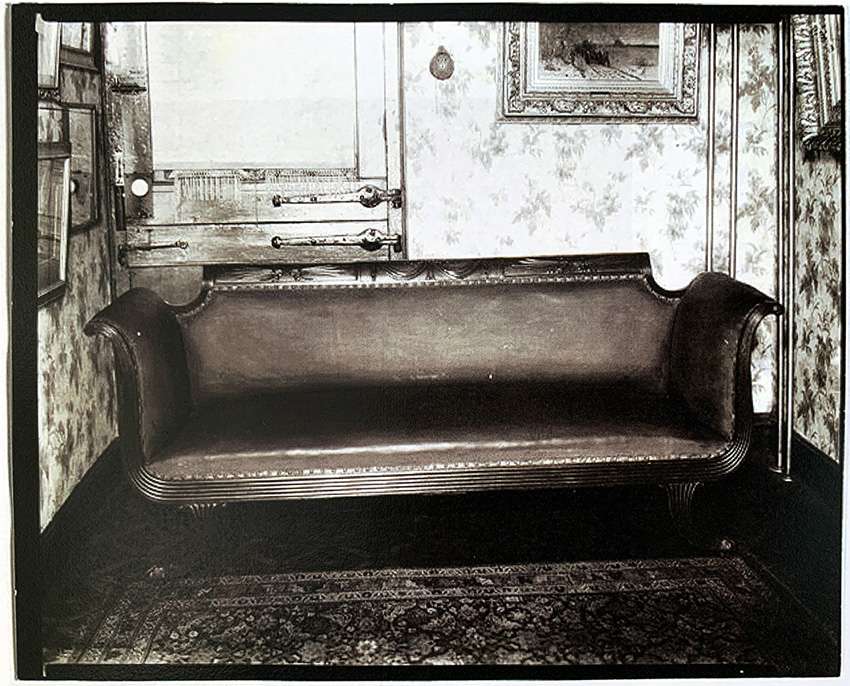

1931 Duncan Phyfe sofa from 1810

photographed before auctioned by Lloyd Hyde (see notes) (HRT)

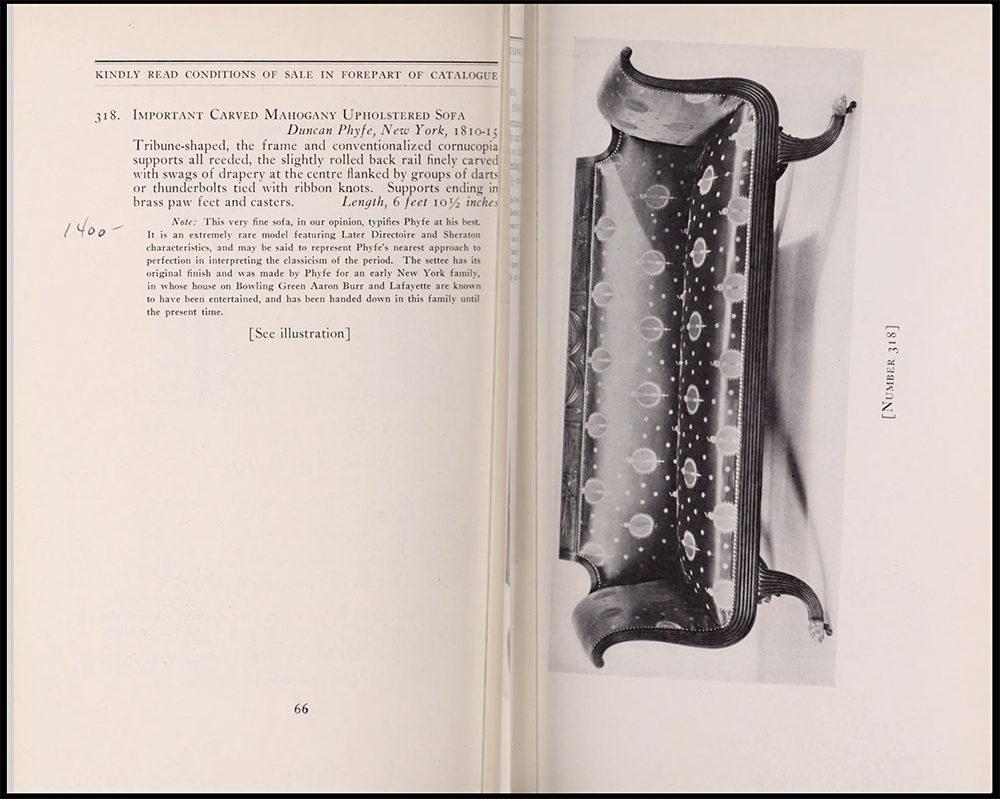

1932 auction catalog with Austen sofa

re-upholstered and sold for $1,400.

c 1933 Alice Austen newspaper clippings

one of several folders of loose clippings (HRT)

1932 passing ship

Austen also began filming ships passing during this time. (HRT)

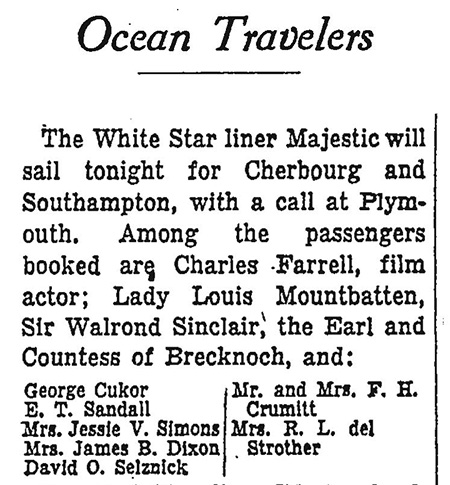

1934 Jessie Vanderbilt Simons traveling with Hollywood’s elite

Simons helped during this time when Austen filed for bankruptcy (see notes.)

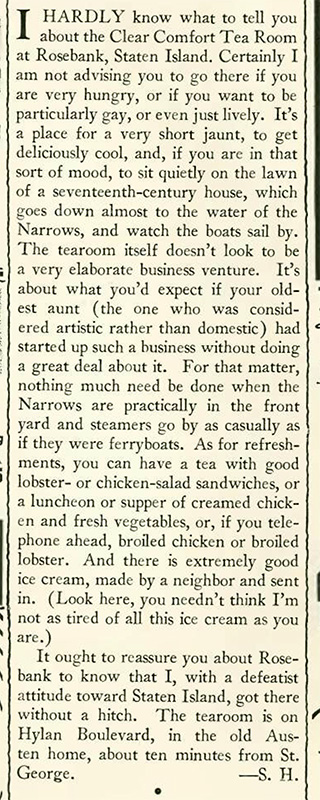

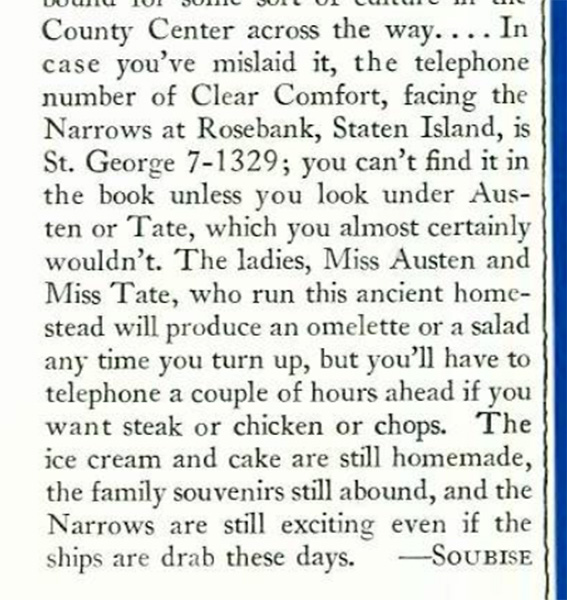

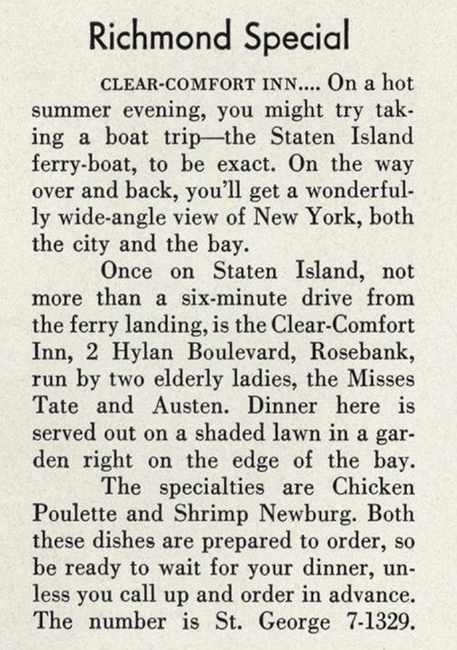

July 1937 review of the Clear Comfort tea house

by New Yorker magazine.

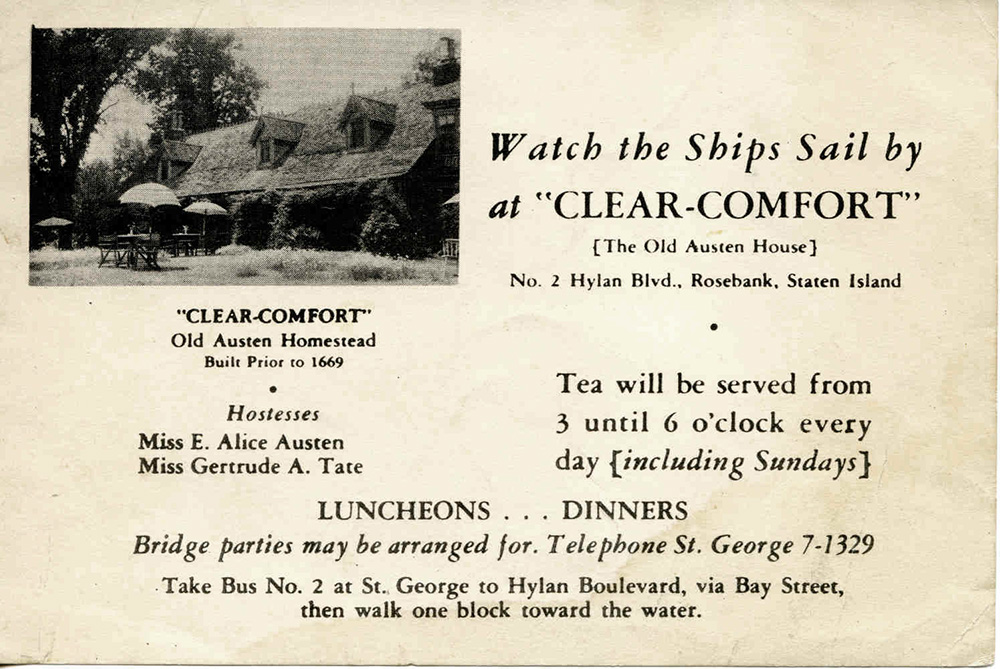

c 1937 ad card for the Clear Comfort tea house

(AAH)

c 1937 tables set for the Clear Comfort tea house

(HRT)

c 1937 Arvid Knudsen with Gertrude & Alice

Still from 16mm film (see notes) (HRT)

c 1937 Arvid Knudsen & Lloyd Hyde with Gertrude Tate

Still from 16mm film (see notes) (HRT)

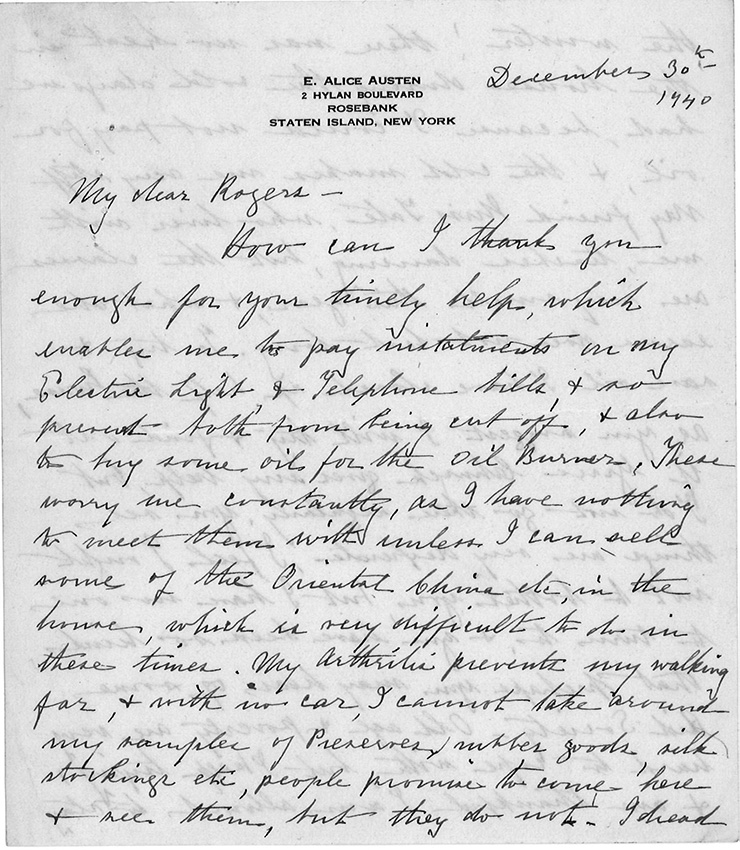

1940 letter from Alice Austen

asking her cousin Rogers Winthrop for help (see notes) (AAH)

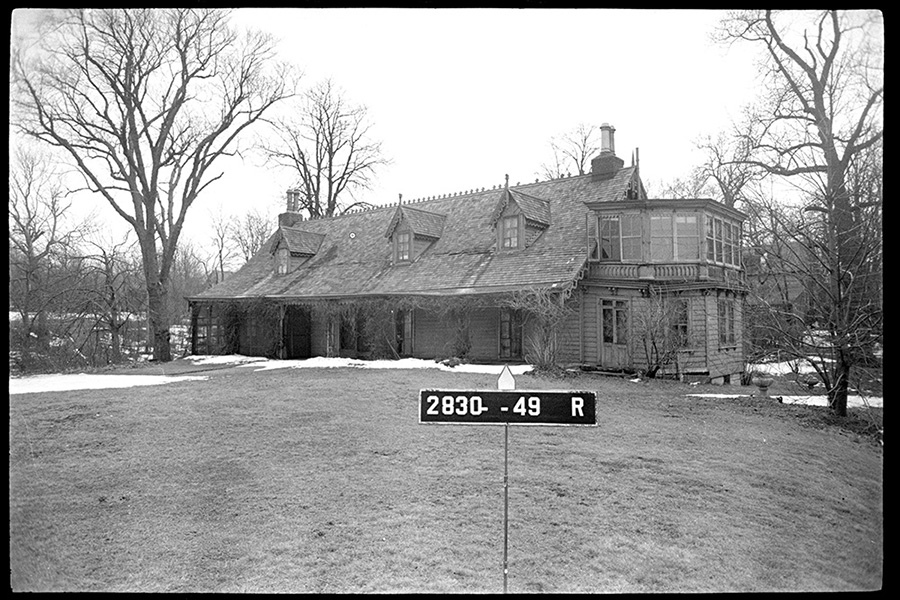

1940 tax photo of Clear Comfort

showing the beginning of its decay.

1887 Wisteria vine

with another vine on tree (HRT)

1893 Wisteria vine

with grandfather John Haggerty Austen the year before he died. (HRT)

c 1925 Wisteria vine

with support, during the time of the Wisteria tea party (HRT)

c 1940 Alice Austen as “wizard”

posing by her beloved wisteria vine (HRT)

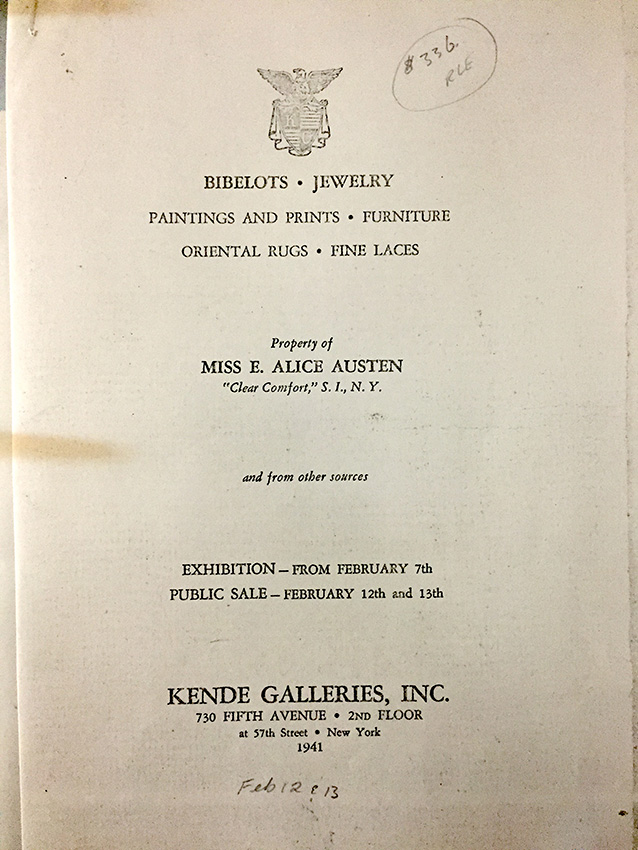

1941 Auction catalog cover page

containing many objects from the Austen home (AAH)

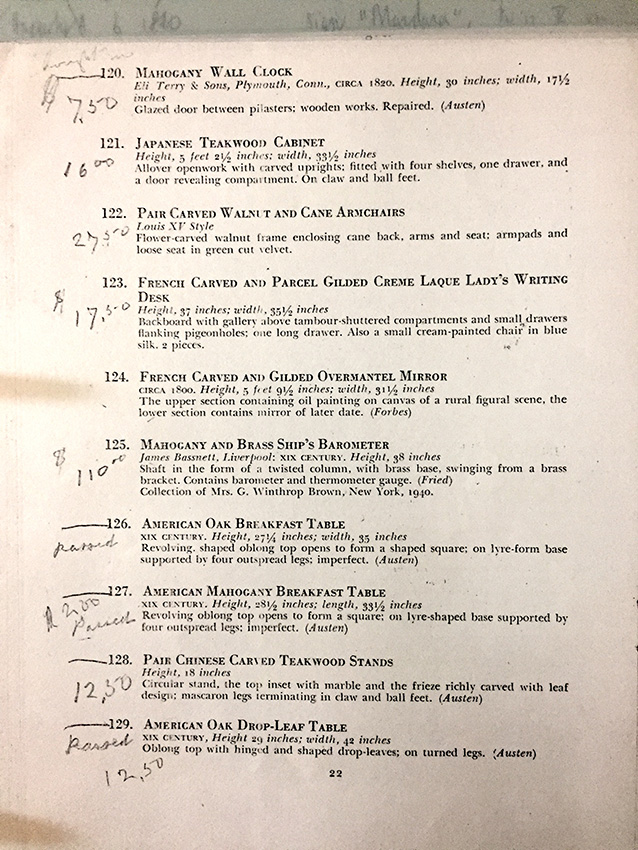

1941 auction catalog page

showing items prices penciled in margin (AAH)

1941 New Yorker review of Clear Comfort Tea House

A catty review.

1941 Austen documented the items that she would sell

Links from chain forged by Townsend ancestor (see notes) (HRT)

1941 part of object inventory to sell

Candlesticks as pictured in the parlor decades earlier. (HRT)

1941 Vogue magazine review

of the Clear Comfort Tea House.

1941 Knoxville Sentinel review of Clear Comfort Tea House

The business closed this year.

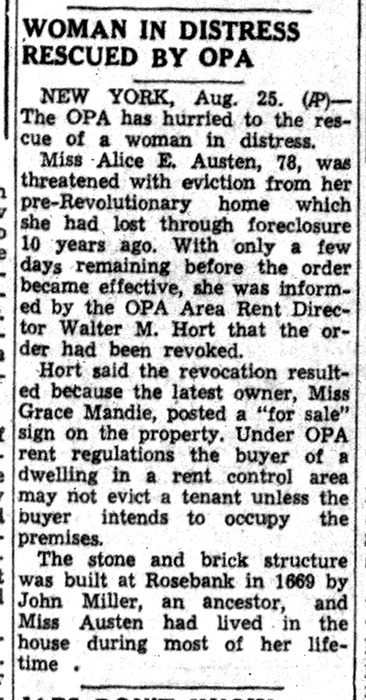

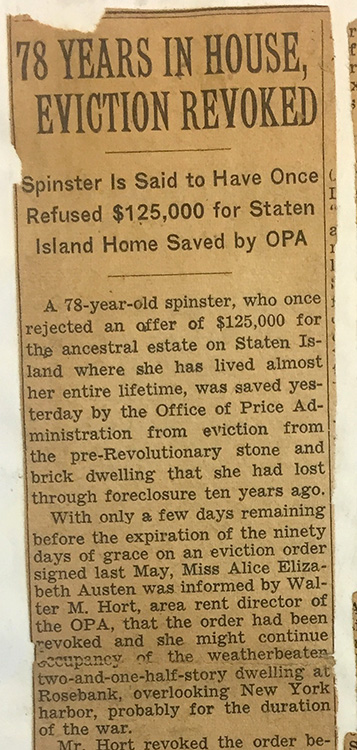

1944 eviction debacle

In 1941 the bank foreclosed, and then in 1944 it sold Clear Comfort to the Mandia family. (see notes)

1944 eviction stopped

The family that bought Clear Comfort illegally offered it for sale. (AAH)

1944 Alice Austen & Gertrude Tate

Photographed by their boarder Dr. Richard Cannon.

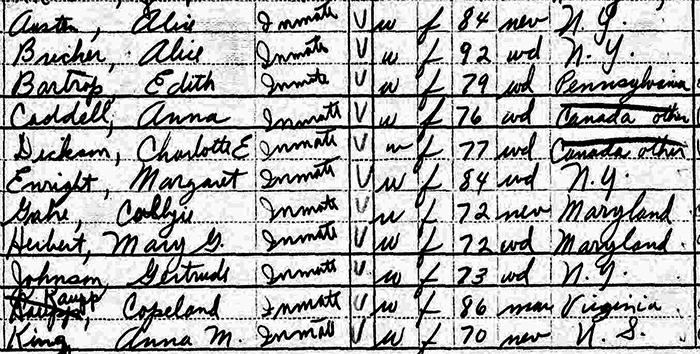

1950 census Mariner’s Family Asylum

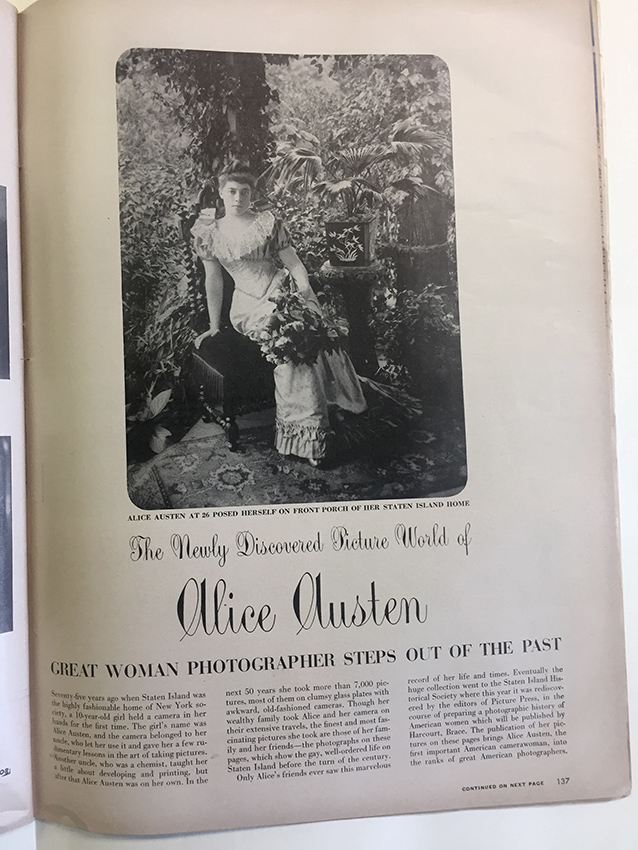

1951 LIFE magazine

showing Austen from 1892 (AAH)

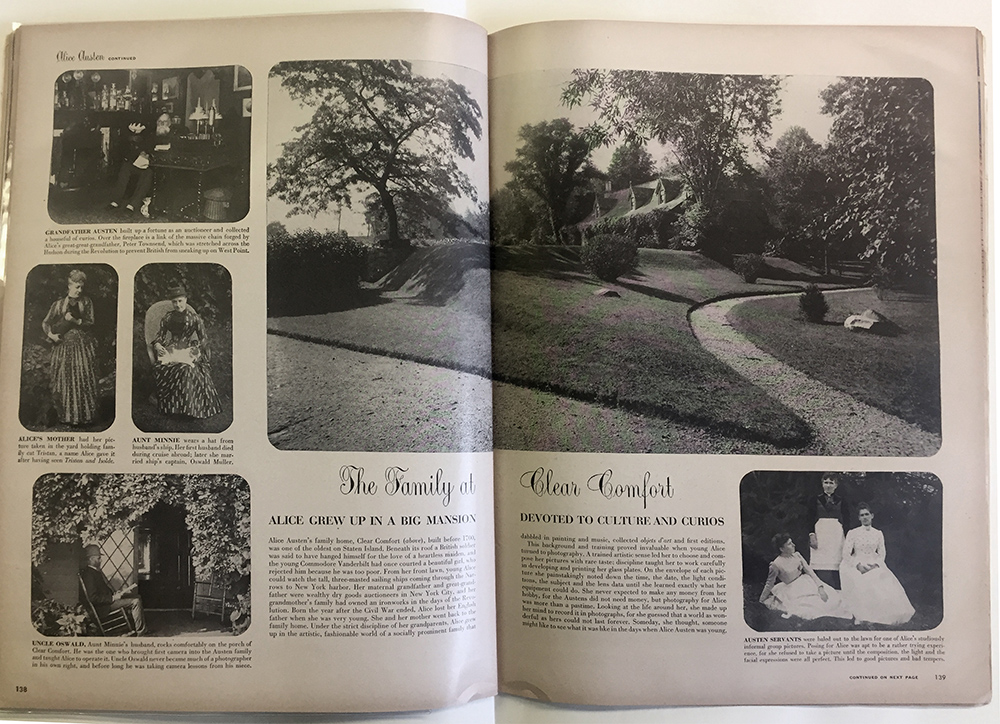

1951 LIFE Magazine

showing Austen’s family and home. (AAH)

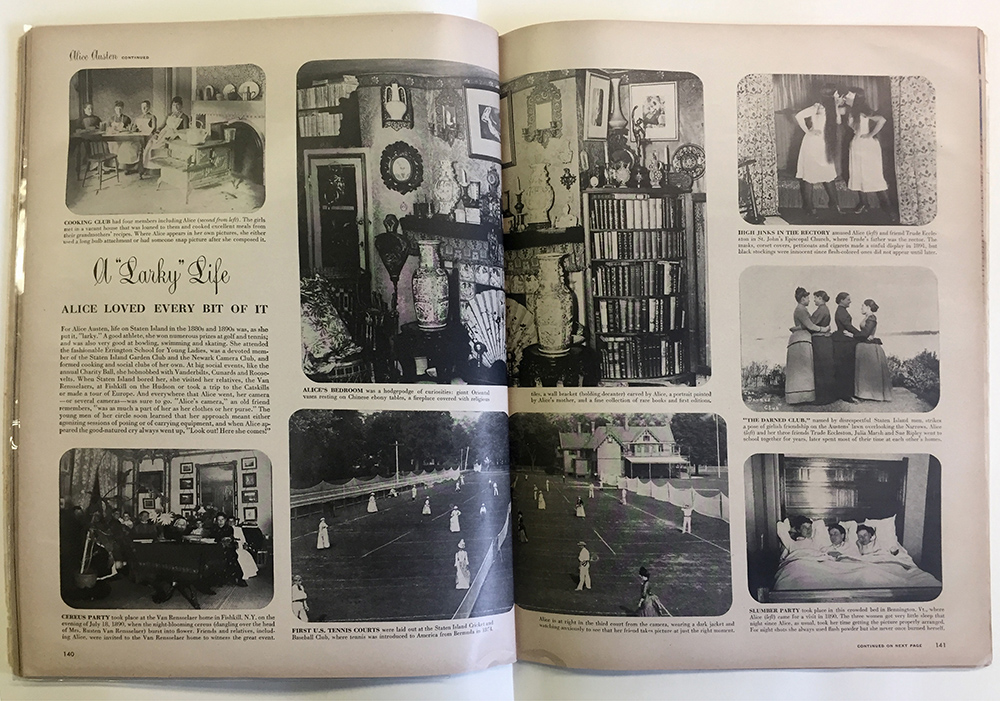

1951 LIFE magazine

showing images as featured in Chapter 3 of this podcast. (AAH)

1951 LIFE magazine

showing photos described throughout this podcast (AAH)

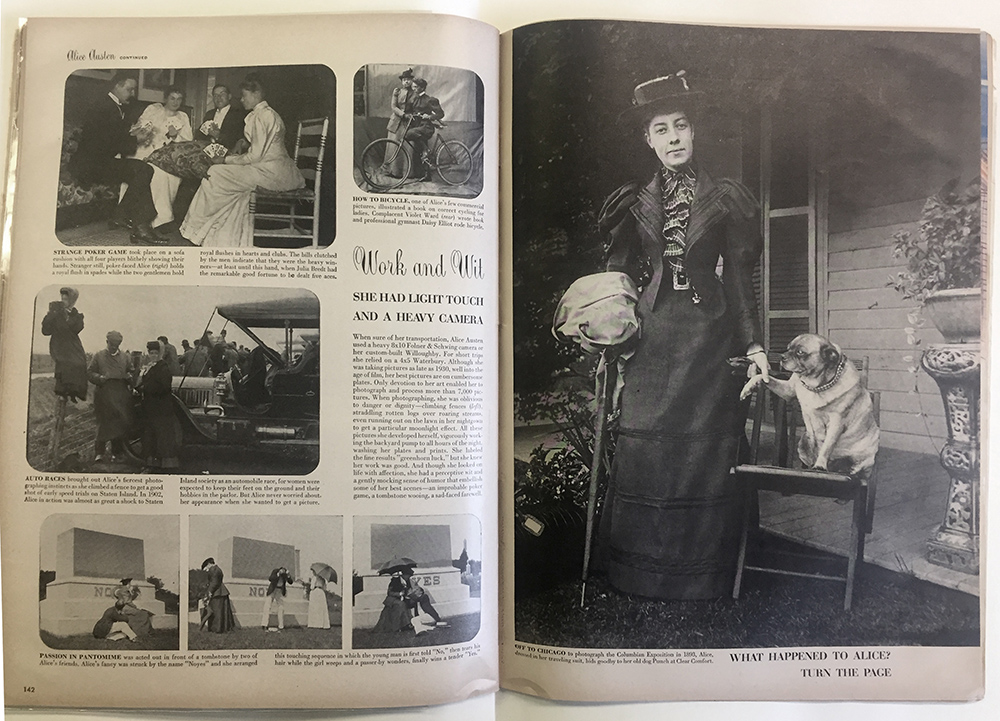

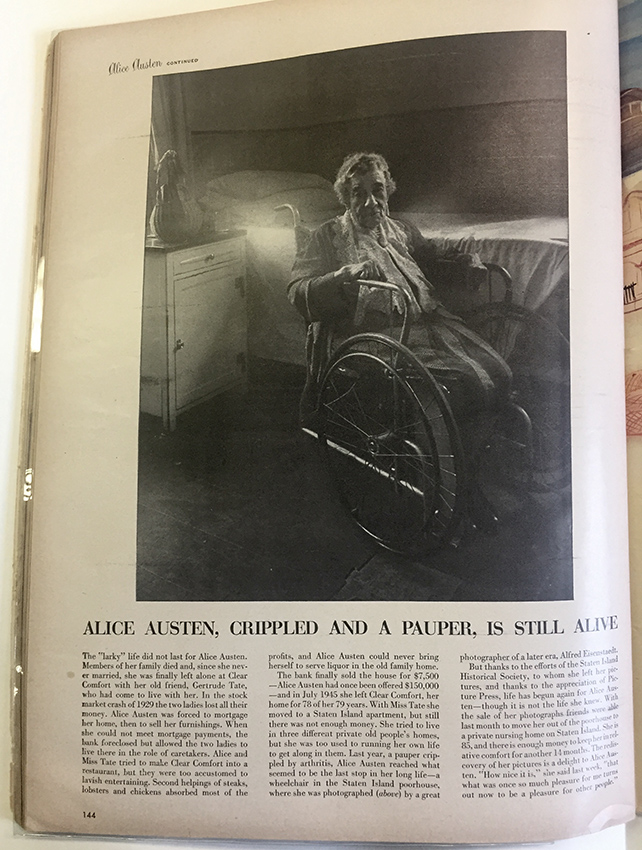

1951 LIFE magazine

horribly sensation final page in photo spread (AAH)

1951 Alice Austen Day at Staten Island Historical Society

with Gertrude Tate, as published in LIFE magazine. Photo © Yale Joel

1951 Alice Austen Day at Staten Island Historical Society

published in LIFE magazine. photo © Yale Joel

1951 very sad photo of Austen at Clear Comfort

Alfred Eisenstaedt and Oliver Jensen brought Austen back to her home for LIFE magazine article (see notes)

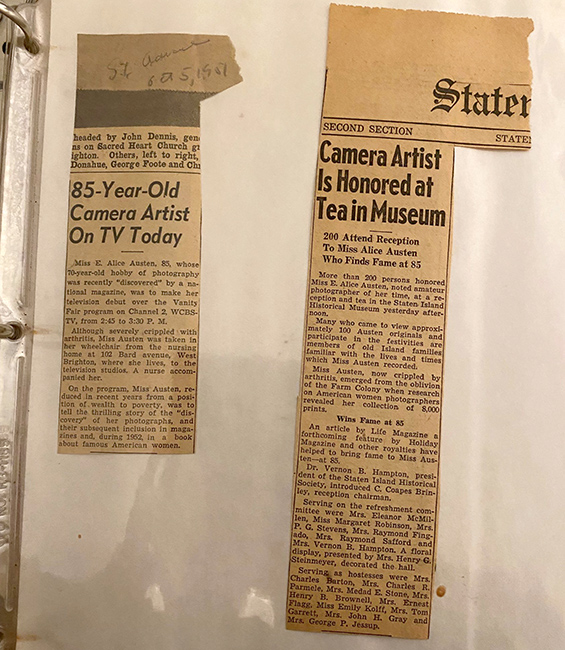

1951 recognitions

Austen appeared on television, and was celebrated on Alice Austen Day. (AAH)

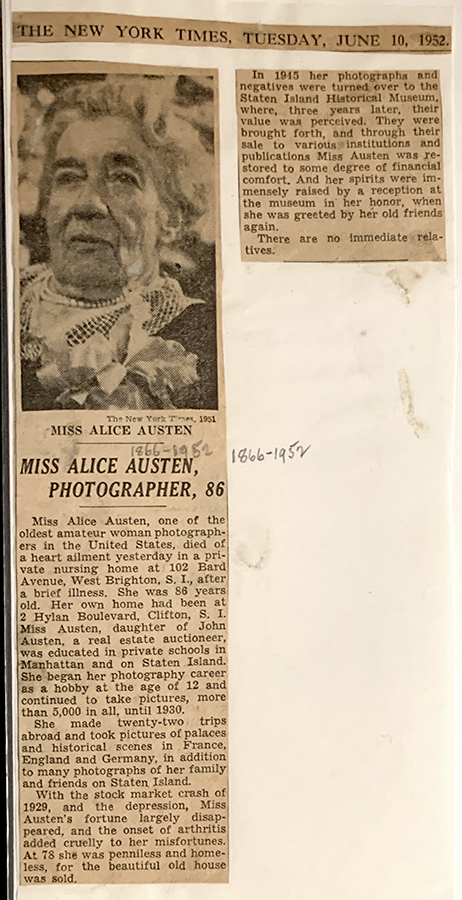

1952 New York Times obituary

Austen died 9 months after being celebrated for her photography. (AAH)

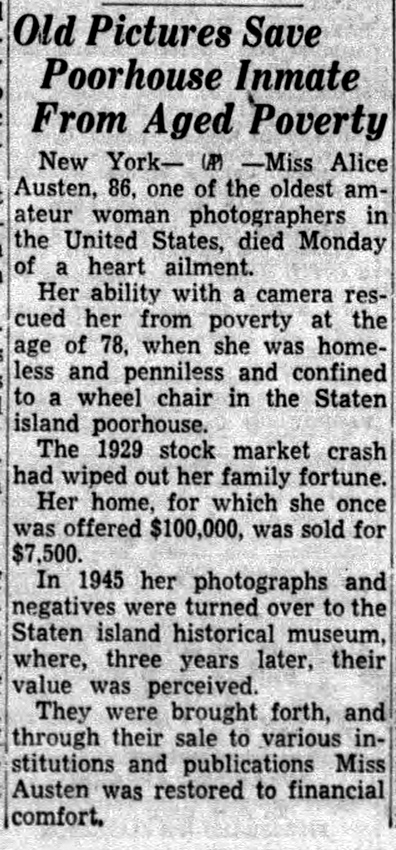

1952 Alice Austen obituary

Austen’s story was celebrated after her death. She would become recognized for the highs and lows of her final years.

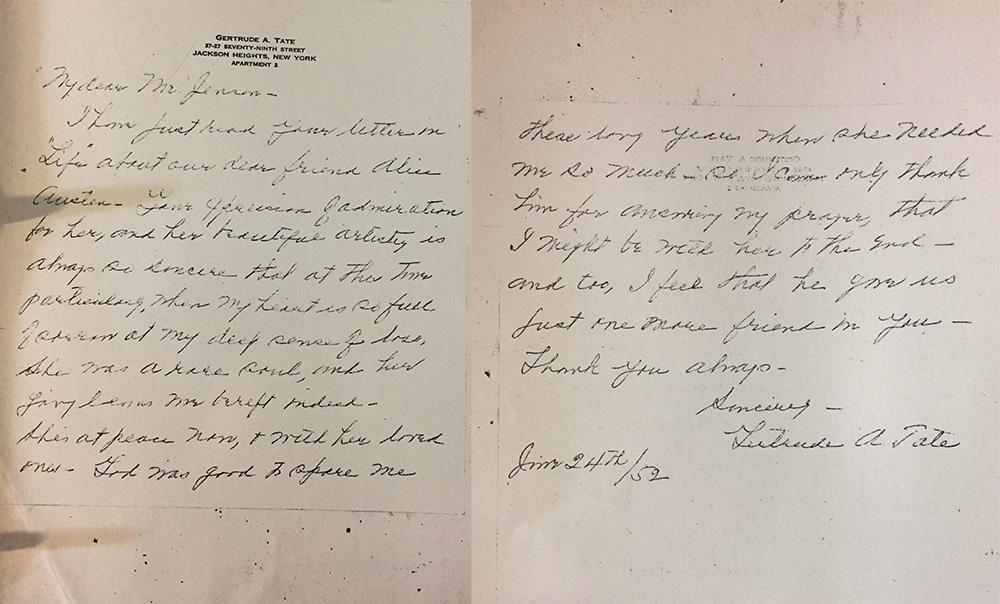

1952 letter from Gertrude Tate

to Oliver Jensen, expressing her devotion to Alice Austen. (AAH)

1951 Alfred Eisenstaedt photo of Austen at Clear Comfort

unpublished photo for LIFE magazine (see notes)

c 1964 Clear Comfort

around the time the Mandia family moved out. Unattributed press photo, collection of Pamela Bannos.

c 1979 Clear Comfort photographed for structure report

© Diana Mara Henry (AAH)

c 1981 Clear Comfort before renovation

© Diana Mara Henry (AAH)

1984 Clear Comfort during renovation

© Diana Mara Henry (AAH)

Clear Comfort today

Photograph by Pamela Bannos.

/*! elementor - v3.8.1 - 13-11-2022 */

.elementor-accordion{text-align:left}.elementor-accordion .elementor-accordion-item{border:1px solid #d4d4d4}.elementor-accordion .elementor-accordion-item+.elementor-accordion-item{border-top:none}.elementor-accordion .elementor-tab-title{margin:0;padding:15px 20px;font-weight:700;line-height:1;cursor:pointer;outline:none}.elementor-accordion .elementor-tab-title .elementor-accordion-icon{display:inline-block;width:1.5em}.elementor-accordion .elementor-tab-title .elementor-accordion-icon svg{width:1em;height:1em}.elementor-accordion .elementor-tab-title .elementor-accordion-icon.elementor-accordion-icon-right{float:right;text-align:right}.elementor-accordion .elementor-tab-title .elementor-accordion-icon.elementor-accordion-icon-left{float:left;text-align:left}.elementor-accordion .elementor-tab-title .elementor-accordion-icon .elementor-accordion-icon-closed{display:block}.elementor-accordion .elementor-tab-title .elementor-accordion-icon .elementor-accordion-icon-opened,.elementor-accordion .elementor-tab-title.elementor-active .elementor-accordion-icon-closed{display:none}.elementor-accordion .elementor-tab-title.elementor-active .elementor-accordion-icon-opened{display:block}.elementor-accordion .elementor-tab-content{display:none;padding:15px 20px;border-top:1px solid #d4d4d4}@media (max-width:767px){.elementor-accordion .elementor-tab-title{padding:12px 15px}.elementor-accordion .elementor-tab-title .elementor-accordion-icon{width:1.2em}.elementor-accordion .elementor-tab-content{padding:7px 15px}}.e-con-inner>.elementor-widget-accordion,.e-con>.elementor-widget-accordion{width:var(--container-widget-width,100%)}

Opening music …

[Narrator]

I’m Pamela Bannos, and this is the final chapter of My Dear Alice, where we will learn of the remaining biographies of the correspondents, who filled in details of Alice’s life, while offering a portal into the culture of the late nineteenth century.

Theme music …

[Narrator]

Chapter 10:

During the decade of the ‘teens, when Alice Austen and Gertrude Tate spent their summers traveling through Europe, Alice’s correspondents’ lives’ changed also.

Even earlier, some of them were the victims of illnesses, and war.

Mr. Gregg, once Trude Eccleston’s fiancé, perished in a battlefield of the 1898 Spanish-American War.

In 1899, 28-year-old Effie Emmons Alexander died after a prolonged illness.

Also in 1899, Effie’s sister-in-law Lou Alexander Richards’s husband died, leaving her with two young children. Lou remarried within a year, had another baby, and then that husband died two years later, leaving her twice widowed with three children at the age of 34.

And during those first years of the new century, other life altering shifts would unfold.

+++++++

Julia Martin continued at her boarding house venture after recovering from surgery for chronic appendicitis. That same year, she bought a corner property where she moved her business, and in the following year, she bought the adjacent lot. In 1899, a local newspaper reported that Julia, her brother Walton, and their Aunt Adelaide were together in Los Angeles. Apparently, Walton Martin was there to deliver their mother’s sister to Santa Barbara. The 1900 census shows 34-yr-old Julia, her 47-year-old Aunt, and a 40-year-old Chinese cook named Sing who had been with Julia for at least four years.

[Julia Martin]

It is Sunday, 3pm, and as usual, I am keeping house. Ang, my house boy has gone to Sunday school, being a Christian. Sing, being a heathen has gone to Chinatown for a good time. My housekeeper is off for the afternoon, and so you see I am quite alone & the house is delightfully quiet & restful.

[Narrator]

A newspaper article from 1902 notes Julia visiting Los Angeles, and later that month she was at a resort near Lake Tahoe. In November it was reported that she had hosted a luncheon at a posh restaurant in Santa Barbara. And then after spending several weeks in Boston, she was on a steamship off Los Angeles. Just a few months later, a New York newspaper reported that Julia was visiting her father in Albany.

And then, the unimaginable.

In my tracing of her whereabouts, the 1905 census locates Julia in the Bloomingdale Hospital for the Insane in White Plains, New York.

When I told this story to a friend of mine, they responded: did she have a family member that was a doctor? And, of course, there was Julia’s brother Walton, the famous New York surgeon who also delivered Aunt Adelaide to California. A newspaper article reported at one point that “of the 535 patients treated for mental diseases in Bloomindale Hospital 419 were committed involuntarily.”

I dug deeper to try to make sense of this and found that Aunt Adelaide was chronically ill with tuberculosis. In early 1902, Julia had petitioned for and was appointed as Adelaide’s legal guardian; soon thereafter, a court order directed a sale of her Aunt’s personal property and this is when it looks like Julia went on some sort of “wild spree,” entertaining at posh restaurants and traveling to resorts. I don’t want to jump to conclusions, but the reports of her excursions occur simultaneously with the legal activities. In the middle of 1903, it was reported that Julia was visiting her father in Albany. She never returned to Santa Barbara.

There is an empty envelope at the Alice Austen House with a May 1904 postmark from White Plains that suddenly and tragically made sense. But I’m heartbroken to not have Julia’s letter to Alice that might shed some light on what happened.

She was still at the Bloomingdale Asylum in the 1910 census; and in 1915; and in 1920.

Her Aunt Adelaide died in 1913 in Santa Barbara. She had a will in which she left the bulk of her sizable estate in trust to Julia. Julia’s brother Walton became Julia’s guardian, and there was also a guardian assigned to Julia’s estate in California who at Adelaide’s death, sold her Santa Barbara house.

By 1925, she had been transferred to another New York asylum called the Long Island Home, in Amityville. Julia Taber Martin died there twelve years later, in 1937, when she was 71 years old.

She had spent half her life in these places. It is really very tragic, terribly devastating, shocking and disturbing.

There’s no other known evidence linking Julia with Alice, but I’d like to think they were still connected. And I shudder to think that Julia’s example contributed to others’ keeping their personal lives in even lower profile. It did dawn on me that maybe Julia was with someone during that extravagant year before she was committed – and maybe it was a woman.

Which brings us back to Daisy Elliott.

+++++++

Ship manifests show Daisy returning to Europe every year from 1900 through 1910. It’s sometimes hard to track who she’s traveling with, but the name Leonie Stamm shows up several times. Stamm was famous in New York for teaching fencing to ultra-wealthy women.

Like Julia Martin, Daisy also has a baffling pivotal event. In 1911, when she was fifty-four years old, and while visiting her family’s ancestral town in England, Daisy Elliott married a man. A widower from Massachusetts, and the father of four grown children, Frederick Fosdick had been the mayor of the town of Fitchburg, having run on the Prohibition Party ticket. Upon her return to the States, Delia Marie Elliott disappeared on the ship manifest, replaced as Mrs. Frederick Fosdick. It was her last time abroad as a married woman and she moved from New York to Fitchburg, Massachusetts. The marriage ended thirteen years later when Mr. Fosdick died. Daisy was 67 years old, and a wealthy widow.

The following year, she got back on a steamship for Europe, traveling with Caroline Lawrence. The same Miss Lawrence with whom she bicycled across the alps in 1897. They would return to Europe together every year for the next eleven years. In 1936, at the time of their last voyage together, Daisy was 79 and Miss Lawrence was 84. Caroline Lawrence died the following year.

Daisy lived on for 14 more years, dying in 1951 at the age of 94.

[Daisy Elliott]

I am rather dependent on my independence, after all; yet most everyone thinks I am so self-reliant – you know as well as anyone the true fact of the case, don’t you, you poor dear?

+++++++

[Narrator]

Obviously, everybody dies in this story, and death is always sad. But all lives can be celebrated, especially if they weren’t conventional ones.

Julie Bredt and Bessie Strong never married.

Here’s Bessie at age 29:

[Bessie Strong]

You can scarcely turn a corner without running up against an engaged person these days. I never knew such a state of things before.

I am to have another chance to be bridesmaid. This will make the third time, but it does not worry me at all.

[Narrator]

In 1905, at the age of 40, she was still living with her parents in their massive New Brunswick, New Jersey home. Bessie’s father was an esteemed judge and she had three brothers who were attorneys; one who would serve as a state senator. Bessie was also active in politics – and as mentioned early on, she was fond of telling Alice about the gifts she received. Here she is in a letter from 1892:

[Bessie Strong]

The wretched Democrats are having a parade downtown, and the drums are beating furiously, all of which is calculated to rile an ardent Republican, like myself. So, if my letter is incoherent, it is attributable to the Democrats. They are responsible for a great deal of “cussedness” in this world anyway. I have been almost heartbroken over the election. Now I am trying to smile and smile and make believe I don’t care but O! I do.

Perhaps you may be interested to know what my birthday presents were.

From mother I had some evening gloves; from father, some money, which I invested in music. Theodore gave me an album for mounting photographs. Miss Van Rensselaer, a pretty little basket from Nassau. Helen’s present was a bonbon dish, Etta’s an exquisite copy of “Hyperion.” My sister-in-law, such a pretty Japanese table cover, pale blue worked in gold; and from Miss Dayton, a Columbian Exposition souvenir spoon. I think I was quite a lucky girl.

[Narrator]

Her brother Theodore – who she mentioned – would become the Republican senator. He married Miss Van Rensselaer who gifted the pretty little basket. They ended up having eight children, including six sons, all of whom became lawyers. Theodore and his large family moved into the family home and named it The Stronghold.

Bessie moved out and lived alone, remaining in New Brunswick for the rest of her life. She died in 1952 at the age of 86. Her obituary noted her as having been one of the board members of a local nursing home that pioneered a home environment like today’s assisted living facilities. She was also president of the Visiting Nurses Association, which was active during the First World War. Her yearly president reports are as thorough as her letters to Alice Austen.

I have little doubt that if Elisabeth Briard Strong had been born one or two generations later, she would have been a successful attorney like her father, brothers, and six nephews. And she’d likely have been a successful politician whose name would be familiar today.

+++++++

Speaking of famous people, Julie Bredt is vicariously connected to one.

In early 1894, she wrote:

[Julie Bredt]

We have been looking at a house in Llewellyn Park and I rather think we shall decide on it, though we shall not occupy it until August some time..

[Narrator]

Two years later, it was reported that Julia’s mother gave a tea for 200 guests at her home “The Pines,” in Llewellyn Park, noted as “the first planned community in America.” Inventor Thomas Edison’s house and factory were down the block from the Bredt’s house. Julia remained in Llewellyn Park for the rest of her life, residing there with her younger sister Ernestine to the end. Of those fifty-odd years, at least twenty of them were sandwiched between Thomas Edison and his phonograph factories. Edison died in 1931.

Julie Bredt became a champion golfer. Her name began appearing in newspapers in 1907 and her appearance in golf tournaments continued being reported on through 1938 when she was nearly 70-years-old. Bredt was also a gifted artist. One of her scrapbooks was acquired by the Alice Austen House Museum – found in a Westhampton, New York, bookshop ten years ago.

Julia Frederika Bredt died in 1949, just shy of her 80th birthday.

+++++++

And so now it’s time to return to Violet Ward …

[Violet Ward]

Maria Emily Graham McKay Ward

[Narrator]

And her sister Carrie …

[Carrie Ward]

Caroline Constantia Ward

[Narrator]

Violet actually shows up in some of the same newspaper articles with Julie Bredt – they competed against each other in golf tournaments.

But Violet and Carrie show up in the area newspapers for other reasons, also.

In 1914, a notorious public proceeding shows Violet on the witness stand defending her competency to maintain her estate, which had been put in trust to a bank.

The Ward sisters had taken separate apartments in Manhattan away from Oneata, the family grounds on Staten Island. Violet stayed on the Upper-West side at 86th St. and Carrie moved into the National Arts Club in Gramercy Park. In 1911, Violet moved back to Oneata permanently, and Carrie returned in 1917 after seven years in Gramercy Park.

It was while the sisters were separated that their estate was turned over to a trust – they were reported to have inherited several hundred thousand dollars from various family members – worth more than 6-million dollars today.

In 1913, they had modified the Oneata grounds to include a Montessori school and had started placing ads advertising “a little colony of bungalows” for “university graduates and others of culture” and “board for a limited number in a fine old mansion, use of a tennis court, and use of a 40-ft sailboat and automobile for tenants who “cooperate with up-keep.”

The ad sounded like Violet wrote it.

In 1915, the trust company was concerned that Violet would spend beyond her allowance, incurring debts that would complicate the trust. She had just bought a new Model-T Ford.

A newspaper more directly stated that the bankers said that Violet “had delusions, which indicated she was deranged.”

52-year-old Violet was a witness on her own behalf, so it’s anyone’s guess why she thought it was a good idea to tell the story that she did.

I won’t go into too many details, but basically Violet testified that when she was twelve, her father had her married to an army officer because he had to attend to emergency business elsewhere and it would put her in the care of the US government. Beyond that, she explained that her father had them go into a tent, where he left them for two days, apparently to consummate the marriage. Further, she asserted that she had given birth to twins – who had died at birth. When her sister Carrie took the stand, she said that she had never heard this story until four years ago, at which time she told Violet not to repeat it.

A doctor representing the bank testified that after examining Violet, it was his professional opinion that she was suffering from delusional insanity. However, the next day’s newspaper headline stated:

[Newspaper Reporter]

“Imaginary Twins of “War Bride” Win Over Jury. Miss Ward’s Delusion Does Not Make Her Incompetent, Staten Island Verdict.”

[Narrator]

That next day – I don’t know, maybe because she had an audience – Violet went further to say that she had been at the Civil War and that Carrie was not actually her sister. Violet was born in 1865, and Carrie was indisputably her sister. The doctor for the defense admitted that there were delusions, but said they were mainly based on exaggerated ideas of her ancestry and were due primarily to extreme egotism. I mean, I’d buy that.

Violet was declared sane, thoroughly competent, and able to manage her own affairs.

It is not lost on me that at this point in 1915, Julia Martin had been institutionalized for more than ten years, and this may go to show the power of money, if nothing else.

Violet and Carrie remained at Oneata through the end of their years.

Carrie appears to have lived adventurously for the next couple of decades, frequently traveling abroad, and in 1931 embarking on an around the world cruise – at the height of the great depression. She turned 67 during that five-month jaunt. More than thirty years earlier, Violet had written to Alice:

[Violet Ward]

Carrie is away and I hope will stay away for some time.

[Narrator]

They came to be known as Staten Island’s eccentric sisters.

Athlete, Author, and Inventor Maria Emily Graham McKnight Ward died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1941, just shy of her 78th birthday.

Caroline Constantia Ward died 6-months later of Ovarian Cancer at the age of 76.

Later in 1942, their home and its contents were sold at auction – the 1915 Model T Ford was still in the garage.

In 1949, Wagner College purchased the Oneata grounds.

For 35 years, the Ward mansion was home to the college’s music department. The choir practiced in the ballroom at the top of the main staircase that Alice Austen photographed in 1897. The staircase that everyone said Violet had fallen down that led to her death; some insisting that Carrie had pushed her.

A student paper titled “Rumors of the Ward House,” explored tales of paranormal activity. The house was sealed in 1983 and was torn down ten years later – the college football stadium now occupies the site, adjacent to the women’s sports field.

+++++++

It was just as Oneata was closed down in the mid-1980s that Clear Comfort re-emerged from its own harrowing spiral.

Which leads us back to Alice Austen.

+++++++

We left off in the first decade of the twentieth century, with Alice and Gertrude Tate’s yearly excursions abroad. These were the best years.

In 1903, in France, Alice and Gertrude appear in a rowboat with Alice standing, steering with one long oar and Gertrude smiling broadly at whoever took the photo. In another picture, taken by Gertrude from her seat, Alice faces her, smiling, while rowing with both oars.

Gertrude is the object of Alice’s gaze, throughout. Here is the great love story of this podcast.

There’s Gertrude Tate sitting at a Parisian café; there she is on a donkey being led on a mountain trail; there’s Alice standing over her on a terrace at morning tea; there she is leaning out a 2nd story window, smiling at Alice, and under a tree amongst a picnic spread; and there she is again in Paris, in a horse drawn carriage, the roof overloaded with steamer trunks – one with EAA, Alice’s initials, stenciled onto it – the carriage door reading in French, ETAT – Tate spelled backwards.

Alice Austen and Gertrude Tate spent three to four months a year traveling overseas throughout the decade. Mid-decade, Austen’s photography was mentioned in a newspaper article titled “Women of Society in Trade,” and she made more quarantine photographs for Dr. Doty – two of which were featured on the front page of the New York Tribune. And Gertrude Tate was teaching dancing classes. But none of this alone would support their lavish vacations.

Gertrude’s family was said to have had

Visit Podcast Website

Visit Podcast Website RSS Podcast Feed

RSS Podcast Feed Subscribe

Subscribe

Add to MyCast

Add to MyCast