A Mouthful of Air: Poetry with Mark McGuinness

The Garden of Gethsemane by Malika Booker

Episode 25

The Garden of Gethsemane by Malika Booker

Malika Booker reads ‘The Garden of Gethsemane’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.

https://media.blubrry.com/amouthfulofair/content.blubrry.com/amouthfulofair/25_The_Garden_of_Gethsemane_by_Malika_Booker.mp3

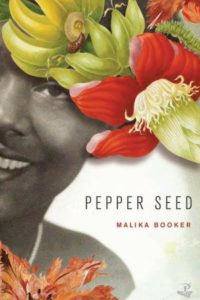

Malika Booker’s latest collection:

Available from:

Pepper Seed is available from:

The publisher: Peepal Tree Press

The Garden of Gethsemane

by Malika Booker

I cannot tell you what the trees whispered to him that night

air ripe with the scent of living, fruits pungent, leaves

clapping, harmonising with the crickets rhythmic screech.

What could trees whisper to a Black man juggling sorrow

on the eve of his catastrophe, face tortured, back bent

from the weight of prophesy, kneeling in damp soil,

thoughts wrestling. Each worry a serrated knife gorging flesh.

Say he was weeping, beating his chest, murmuring big man

don’t cry, wanting to unshackle from his father’s heirloom

but what Papa does not force their son into a square box,

each corner reinforced with the black tar of hardening expectations.

And the garden was not a tonic. When he spoke to the leaves,

did they not turn their backs, curl into their spine to recede

into their own nourishment, leaving him to keep his own vigil

on this seemingly ordinary night, the eve of his prophesied death.

And those disciples! My soul is exceedingly sorrowful, even

unto death, tarry ye here, and watch with me, he asked them.

Oh those fickle hard ears men, how their snores became bass

in the ripe music of this garden. How they will regret

not catching the tremor in his voice, the slight waver

each pause. Regret will sit heavy on their chests

whenever they remember this garden, and not reading

the nuances, his pathos, between each utterance of his asking.

Sit ye here while I go to pray. Meaning, sit so we can converse

in the language of grief. Meaning, it is my last night with you.

Let us partake in the language of wake, lick down dominos,

and make ole talk, come nah man. Meaning, be my brothers tonight.

Come lick down double six and rock the table, disturb the still

of the night. He wanted ole talk, lime and labrish.

My soul exceedingly sorrowful even unto death.

but his brother’s snores mingled with the owls hoot and the leaves

turned their backs, while his kinfolk sprawl out in sleep.

The nails, the nails

bones breaking, splintering

bearing timber on your back

like a donkey carrying load

Say he is weeping and beating his chest muttering

big man don’t cry, Mourning his lack of ordinariness.

Mourning his body will not rot, worm and decay.

Maggots will not feed on his flesh.

Now his palms dig into the soil, earth in fingernails

shifting the dirt, man’s flesh is moulded from, burying

this sorrowful weight, then standing as the stuttering

light of morning approaches.

Interview transcript

Mark: Malika, where did this poem come from?

Malika: So, the BBC contacted me last year during Easter, and asked me if I could write a poem for them. And they’d allocated, it was to commemorate Lent, and Easter, and the countdown to Easter. So, they allocate each poet a different night, or a different day. And I was given the night before Jesus died when he went into the garden. And he went into the Garden of Gethsemane. And he was in there with the disciples, and the weight was heavy because he knew it was just before his betrayal. It was the day before his betrayal. And he also knew what was to come, that he was going to be crucified. So, he’s in the garden, and he’s very laden with it.

And so I approach that, but also I’m studying at the moment. And I’ve had this project I’ve been working on for quite a while, which is kind of Creolizing the King James Bible, placing the characters, the geography, and the language of the Caribbean within the King James Bible.

Mark: Wow.

Malika: And seeing what comes up in that, what comes up in that space, how that helps to think about colonization and racism, and what happens in that space. And also how that helps to think about gender after the postcolonial project and its legacy, but also in terms of women as a whole and how they’re situated there. So, in a way it’s… Some of the poems are becoming quite universal as well as being specific to place. So, when they ask me to write this, even though I’m concentrating on the Old Testament for the Ph.D. because you have to be quite specific, it felt like I could continue exploring this within the New Testament.

Mark: Wow. That’s quite a project. I want to come back to the King James because that was obviously one of the things that jumped out at me. It was the different registers of the language within the poem. But I want to go back to that moment of commission. I mean, what was it like when they said, ‘Okay, you are doing the Garden of Gethsemane.’ How did that feel?

Malika: Well, first I was like, ‘Yay, this is the Bible! I’m here. I’m in the Bible.’ And then I think the process of imagination comes, what I do is I write out the whole text. We did workshops with Mimi Khalvati. And I remember her saying, ‘Sometimes if you like a poem in a book or to understand it, write it out. And in the process of writing, you start to understand the musicality and the lyricism, and some of the things that the writer does.’

So, the first approach I take to that part of the Bible, is that I write it out. So, I write it out. So, I wrote out Matthew 26 from verse 36 to 46, from the King James Bible, and then I underline key lines. Like, I underlined lines like, ‘Began to be sorrowful and heavy.’ ‘My soul is exceedingly sorrowful, even onto death. Tarry ye here and watch with me.’ And I underlined things like, ‘Prayed, saying, O my Father, if this is my cup, may it not pass away from me, except I drink it, thy will be done.’ So, I understand what I realize now was kind of like the emotional register. And then I start writing, ‘How is he feeling?’ And I start writing a kind of essay or a kind of sentence, like, how is he speaking? What is he doing? How does he feel? And I start to kind of humanize.

But also interested me though, in the aftermath of George Floyd as well, the idea of this man kneeling to pray with his neck down became quite powerful. And so George Floyd keeps leaking into the poem. But also I wanted the… What I’m also playing with is how I move from one register to another, although I don’t do it as much here. But in some of the poems, I’m praying from moving to the person in the poem, speaking so that big man don’t cry, so that the person who is in there is given voice because in the Bible, a lot of people are erased. They’re spoken about, but they don’t speak.

Mark: They’re spoken for.

Malika: And then the other thing… Yes, they’re spoken for. And then the other thing I wanted to do was also to still get a bit of how I move from vernacular, from Caribbean into that kind of…and to keep some of the King James register. So, lines that say, ‘He was weeping.’ ‘And the garden was not a tonic.’ So those are taken from, all ‘those fickle hard ears men’. That language, that linguistic kind of, that cadence is taken from the rhythmic qualities of the King James Bible.

And I think about it, ‘the crickets’ rhythmic screech’ is kind of, like, ironic. It’s me, the poet kind of almost saying to myself, ‘Remember that you’re trying to get these rhythmic echoes within the poem.’ But also it’s humanizing. We just see this person, he went to the Garden of Gethsemane, and he’s such an idol, and a God, and a figure in Christianity. But what is the human, what is the torture, and what lets you say, ‘O Father, if this is my cup, may this not pass?’ What is the mood of someone who’s doing that? And so that line 42, verse 42 in the King James Bible became kind of, like, the underlining tone, the manifesto for the poem in a way.

Mark: And that question about, what is the mood of him? I think this is the point in the New Testament where Jesus is really at his most human, isn’t he? Because, I mean, I guess in…

Malika: Yes.

Mark: Jesus goes from the spectrum from, really divine Jesus to really human Jesus. And I think this is probably the furthest at the human end of the spectrum, where he’s questioning, he’s frightened. He’s not sure of himself the way he is in public, Is he?

Malika: No. This is him at his most vulnerable, and he also wants companionship. He’s aware that he’s going to be taking a burden on his own now. And his flesh, it’s going to be painful and stuff. And so he really needed the disciples that night, he had need as well. And so I wanted that in there as well. And I wanted to explore, how would this sit in the Caribbean wake tradition or ritual of Nine Nights, of watching.

So, when someone dies, sometimes from the moment of death, we start going to the house and you’re watching, you’re sitting with the family. In the olden days, the body would come into the house as well. And the night before, the family would sit with the body, right? And then during the wake, there are things that happen, like, people play dominoes, and eat food, and share food, and share stories in that wake tradition. So, I’m pulling some of that into here as well, very subtly. He wanted them to sit down. But it’s really ironic, he wanted them to sit down and play dominoes because it’s his own wake. So, that’s unusual, right?

Mark: Yeah.

Malika: Because the body’s usually left. And then I wondered about nature. If this is said in the Caribbean, then nature plays a big part. So, I started reading up about that region, and the olive trees, and what was being said about the olive trees, and what were being said about the trees. So, I started doing research about the trees. And then I saw something in my research about leaves curling in, in the night. So, that’s nothing to do with the olive trees, but these leaves curling into the Nine Nights. And so that was…and then I thought about the idea of leaves whispering. You know, that we always talk about leaves whispering, it’s such a saying.

So, I started to think about all these things. I started to make a kind of tapestry or, it’s like a paint, a sketching, the scenery, but most of that scenery did not go in, what was the ground like? Was there dew? So I know that there’s dew in the…there was dew. You know, dew is saturating the place, is dew-like tears. And some of those images didn’t come into the poem. But that kind of exploration happened and then got discarded.

Mark: So, I have an image of you kind of walking around in the imaginative space where you’re doing research, you’re reading the King James Bible, you’re thinking, George Floyd is in your mind as well. How do you navigate that space? Because these are some big weighty topics in and amongst some, little technical questions, like, well, was there dew on the ground? I mean, how do you find the right orientation within that space?

Malika: So, it’s funny because as you’re talking to me, I’m looking at my notebook to help me to remember because you get the poem and then you forget all of that work before. I think it started a bit, and what did the trees whisper that night? That was the first line of the poem in a couplet. And what did the trees whisper that night to the big man whose will was at the crossroad? I started thinking about this crossroad. And so that was the first couplet before the editing.

And so I started to write, but also I started to kind of write, what do I want the poem to do? And I wanted the poem to score an emotional landscape. So, I started to get, what is the emotional landscape? It’s need, it’s loss. And how does that manifest itself? Well, the trees are whispering. There’s ambiance, it’s almost filming, the poem is almost filming. What do you do in grief? You weep, you beat. And then I cannot tell you, it’s like it came out in my free writes. I cannot tell you how he was feeling that night. I cannot tell you how he can… You know, so that kind of came. And then this, and, and maybe he must have, and maybe he must have.

So, looking at the free write, I started to see that, that wasn’t a kind of anaphoric. I can never say it to anaphoric, which is when you repeat something at the beginning of the line over and over, and also it felt really good to do that because that feels like a biblical, almost a prayer place. Because in litany…

Mark: Yes, yes. Very common. Yeah, yeah, yeah

Malika: Yeah. And in prayer, that’s what happens, you do that and we said, ‘and in the name of the father and, dah, dah, dah’, and you have that repetition refrain. So, I thought that might add the element of prayer in the poem. And so I’m starting to kind of construct the poem, that those suppositions. And then you start working on the poem line by line, then all of that kind of becomes the foundation that you’ve forgotten, but it’s there in the body because now you’re, like, really you’re on the blank page, trying to get the words. And you’re working sometimes line by line, sometimes pull in lines that you’ve got in notebooks that you put down.

So, I had something, like, ‘I cannot tell you what the trees whispered that night. Someone’s air is desperate for empathy. What did the trees whisper to my tortured face, my body bent from the weight of forecasts and complexities? Me kneeling in the soil, my knee on the sogging earth, in the rain, in the dew, and the air ripe with the scent of the living, and the fruits are pungent in this damp evening?’ Now, you’re hearing all these extra words, right?

Mark: Yeah.

Malika: But that’s me exploring the idea. And then it’s, like, it’s brutal, rigorous editing.

Mark: Right, right. So, we’re going to come back to that process in a moment. There’s a couple of characteristics of your Jesus that I think I would like to pick up on here. So, one is you describe him as ‘a Black man juggling sorrow’. Now, we know from…you know, the typical iconography is he’s very often white, he is Caucasian, isn’t he? And we know that he almost certainly was not. So, on the one hand, you’ve emphasized the Blackness.

And also, I think it’s very interesting. You have, I think you repeat this phrase, ‘Big man don’t cry,’ so Jesus struggling with his masculinity there, if you like. And again, normally the way he’s represented is it’s not exactly a feminine, but he’s not a macho. We don’t get macho Jesus very often. And maybe that outburst in the temple in the market, but he’s normally quite passive, quite gentle, qualities that would not be associated with the big man. So, I’m curious about how you came to this imagining of your Jesus.

Malika: Well, fundamentally enough, right, the poem is quite… As I’m talking to you about it, I’m like, ‘Wow, this poem is doing quite a lot.’ It is exploring masculinity as well. One of the things that I suppose the bigger project is doing is it’s looking at this very patriarchal book, right?

Mark: Yeah. It doesn’t get a lot more patriarchal than that!

Malika: It doesn’t get a lot more patriarchal than that! [Laughter] And it’s unpicking some of the problems with patriarchy. And one of them is this notion of the stoic masculine figure, you don’t show your emotions. But I beg to differ. I think there are lots of times when we see Jesus outbursts, not only… There’s times when he tells off the apostles, there’s times when he speaks to them in this kind of proverb. There’s times when he… It seems like when he’s having emotional outbursts, except for the one in the temple. There’s the other time when he’s in the desert being tempted by the devil.

And it seems like there’s a solitude whenever he’s experiencing agony, for me, I suppose. There’s a solitude when he’s experiencing agony. You know, even though he had the thieves with him on both sides of the cross, he’s the one who is nailed. They’re not nailed. You know, he’s the one who he’s still alone. Even when he’s carrying the cross, he’s still alone. So, there’s this thing, and I wanted the ‘Big man, don’t cry’ to represent that, but I also wanted to explore, not only… So, it becomes universal because it becomes about the bigger masculinity, but it also becomes about masculinity within the Black community, within the Black diasporic community, and obviously, within the Caribbean community, how man is, the expectations we have of males. And what is that expectation? ‘Big man don’t cry.’ How is that expectation perpetuated on the Black body when the Black body isn’t seen as a vulnerable body? And how does the Black body enact and perform in a space where the things enacted on it call for vulnerability, call for emotions? I mean, God, I’m exploring big things in this small poem.

Mark: Well, it’s a very big poem. And it feels like it’s a poem with a big heart to contain all of that. And I’m also curious about this ‘I’ at the beginning. ‘I cannot tell you what the trees whispered to him that night.’ And, all the way through the poem, we’ve got, as you say, Jesus as a very solitary figure, and he’s desperate for company. He’s desperate for someone to sit with him and witness. I mean, I’m curious, who is this ‘I’? Because it strikes me that that I, maybe the poet, is witnessing, is waking with him. Would that be going too far?

Malika: Yeah. I think ‘I cannot tell you’, this is a leftover from that, from when I was writing it, because in one of the free writes that I did, it was like, ‘I can tell you, and I cannot tell you’, all right?

Mark: Okay.

Malika: To enable me to understand what I knew about the text, what can I tell you about this? What can I tell you about this imagining where I’m building, and what can’t I tell you? And one of the things I realized is I can’t tell you… So, I realized I couldn’t tell you a lot, I couldn’t tell you what he was wearing. I had this litany. But I kept coming back to the trees, and I felt like the trees would be an anchor. And I felt like I wouldn’t understand the trees whispering as a poet, but this is the Son of God. He understands everything. He would understand nature as well. He would understand. But even though the trees are whispering to him, they’re not communicating with him, they turn their back, right?

Mark: Okay. So, maybe we can focus a bit more on the actual words and the writing process because you’ve mentioned the… Did you say it started off in couplets?

Malika: It did. It started off in couplets.

Mark: And what was the evolution of the form of the poem like?

Malika: So, it started off in couplets, and then it became a block form as I tried to kind of chisel and work on things. It became a really big block as I was working on it. The couplets was… I felt like the couplets had a lightness to… And I was feeling my way. Sometimes you feel in your way trying to find the personality of the poem. And the personality of the poem, because the first thing you do, when you look at the poem, is you see the shape. And the shape gives you some idea of the personality of that poem.

So, I think I wanted it in couplets because I was thinking of lightness, and of kind of, like, a light song, right? Like, I’m singing this. Like, this idea of singing someone through their wake or singing someone through their… When your heart is not at ease, you want song. And then it became a block because I was, like, I’m trying too early for the form. I actually need to work out what is in this? What is in this poem, and what is outside of the poem? And the block helped me to kind of edit out the extra words.

And then I started thinking about… and we come back to Mimi Khalvati, who I think is like the superwoman of poetry, and such a seer. And I remember something that’s never left me, and we talked about the weight of a form. And so the weight of a form, the quatrains, the four, the four-line verse presents a heaviness. It’s almost like a table. It’s almost stoic. It’s almost heavy.

And so it started to feel like… At first, the first line, the first three line, so it starts with a tercet, that three-line stanza, three-line verse. And that’s almost a sleight of hand. That’s almost like a setup that’s not going to be continued because the trees are whispering to him. Everything is teeming with life, there’s noise everywhere, right?

Mark: Yeah.

Malika: So, that’s why that is there, that tercet. And then it goes into the heaviness. He’s on his own. None of this noise is…He’s silent there. And then the whole poem is in quatrains, in four-line stanzas, because of that heaviness. And if you think of hymns, if you think of hymns, and I think of hymns we sing at funerals, they’re usually, like, four-line verses, right?

Mark: Yeah, yeah.

Malika: And then there’s this break, almost like it’s too much. And there’s this break when the poet and even he sees ahead, which is unusual. And I didn’t know whether that would work. And I thought when I sent it to the BBC producers, they’re going to come back and say, ‘What happened here? The poem kind of revolts.’ And so that… yeah.

Mark: So, that’s three stanzas from the end, it suddenly breaks into these short lines, the nails, the nails, bones breaking, splintering, and so on?

Malika: Yes. Yeah.

Mark: And obviously, it does stick out, particularly if you’re listening, folks, and go and have a look on the website, you’ll see the form changes quite radically in that stanza. So, tell me about that decision to, A, well, how did that happen? And B, the decision to keep it?

Malika: So, I thought, ‘Oh my God, you’re seeing ahead to what is going to happen, and this is making the weight even more. Can we see with you?’ Like, can we see because you are… it’s that line in the Bible I think when he says, it comes from that line in the Bible when he says like, almost take this weight, like, ‘Father, can you take this weight from me?’

Mark: Oh, that’s right. Yeah.

Malika: You know, he says, ‘O my Father, if this is the cup, may it not pass away from me, except I drink it, thy will be done.’ And that line, remember I said that I extracted these lines. Underneath that line, underneath that extraction, I would write things. I would write thoughts and stuff. And that line was like, ‘What could he see?’

And then also like… I grew up Catholic, and the thing is, like, Palm Sunday, or when you think about the palms, I would just hold my palm. It just felt like a fragile thing, and try to understand nails going through my bones, right? And it just felt like the most horrendous thing you could do to a human. And so I wrote down what would stick out in the journey as the hardest thing that you feel like you can’t base. And I thought it was the nails, the nails, and then the carrying, the humbling, the subjugation of having to carry timber on your back, of having to pull this thing, the degradation of that.

And then also, for me, it reminded me, in terms of body being sacrificed, it reminded me, again, of the bigger project of the colonial legacy of slavery and the enslaved, where the body is not at the will, and the body is carrying. And then timber, for me, is one of the things that was… You know, we talk about sugar cane, and we talk about rum, but we don’t talk about mahogany, and we don’t talk about timber, and we don’t talk about the wood.

So, all of that… I mean, God, it’s big, isn’t it? There’s a lot of big writing, there’s pages, poems take pages to then get down into that. And it’s agony because I don’t know where it’s going. And I don’t know where all these big ideas are going because the poem has to be so precise. So, that came up, and it became like a litany, it came in your head, your thoughts. You know, when you don’t want to do something, application form, the application form, I have to write the application form, right?

So, it became like that the nails, the nails, almost like we are in that worry. And I’d say his worry was a serrated knife earlier in the poem. And here, the reader enters into that serrated knife. They enter into that mind for a second, and they’re in the future. And then we come back, and that’s repeated, say, he’s weeping, beating his chest. And now we understand it, why he would weep. You know, and ‘mourning his lack of ordinariness’, you understand what that lack of ordinariness is because his body will not be buried like anybody else. And actually, in here, he wants his body to be buried and go into the earth.

Mark: And that’s an extraordinary thing to mourn, isn’t it? Because the rest of us have to mourn the fact that we will go into the Earth. But he’s feeling… It’s incredible moment in the poem is really he’s alone in the absence of death.

Malika: Yes.

Mark: Which, you know, the rest of us have to face.

Malika: Yes.

Mark: And picking up on this idea of heaviness, because I think you’re absolutely right. You know, the four square, long lines of these quatrains, it is like a big old heavy table, maybe a mahogany table. And another thing that’s really heavy is the language of the King James Bible. And you’ve got this amazing contrast or amazing dance going on between that register and the Caribbean vernacular throughout the poem. Can you say something about that? Because, there are more user-friendly, modern colloquial translations of the Bible. What made you stick with the King James? And what effect did that have?

Malika: The King James is exquisitely beautiful language-wise for a poet. ‘Sit here while I go to pray.’ You know, some version says, ‘He wanted them to sit with him while he went to pray.’ Well, no. As a poet, that’s not doing anything.

Mark: It’s not on the same level, is it?

Malika: No, no. ‘My soul is exceedingly sorrowful, even onto death. Tarry ye here, sit with me.’ So, to play off that language, that beautiful lyrical, there’s a lyricism to the King James Bible, first of all. There’s also the fact that growing up in the Caribbean, the King James Bible is embedded in a lot of our culture, in a lot of our cultural, social, religious, everything. So, I thought it was all right to be Catholic and have the King James Bible because the King James Bible was in everybody’s household. When I came over here, people were like, ‘No, no. The King James.’ So, people have the King James Bible, they register birth there. There was a time when people weren’t allowed to read the Bible, it was felt that, my ancestors shouldn’t read, shouldn’t learn to read. And some people were prosecuted for reading the Bible, and it’s the same King James Bible, right? And the King James Bible is if you listen to Reggae lyrics, if you to… it’s the most quoted, most of the lyrics come from the King James. A lot of the proverbial language within the Caribbean comes from the King James.

So, the language of the King James exists, and it’s blended with this lyrical vernacular of, if it’s Trinidadian, if it’s Jamaican, if it’s Guyanese, the King James Bible is there. And I wanted to explore that, and I wanted to understand what that is because also the King James Bible is the Bible that, people use, the planters, the plantocracy use that Bible to validate and to pick lines in there to validate slavery.

But then the enslaved used the King James Bible to understand, to use as a kind of vision, or mythical, or a space for escape, for freedom with the Exodus, with Moses and the Exodus from Egypt, and the promised land, and freedom, and taking flight. So, there are all these really… And so I really have always been kind of excited and curious about this mix. And so I don’t know if you notice, but sometimes when the thing comes in, when the ‘Sit here while I go to pray,’ just a few lines later ‘and make ole talk, come nah man’. I usually try and explore the vernacular, not far from the biblical text. I wanted it to be much more, but this point was like, ‘No, I’m not having it.’ Because the poem kind of dictates what it’s doing. It takes over from the poet.

Mark: Yeah. The poem has its own way, doesn’t it?

Malika: So, it’s all of that really.

Mark: Well, thank you, Malika. I mean, this is one of the things I love about poetry is that you can look at a poem, and you can spend time with it. And the more you look, the more you find in it. And with finding… I mean, even, the first few times I’ve read this, there’s an extraordinary richness about it. But it’s really, you’ve opened up several other layers and dimensions of it for me today. So, I think it would be a really good moment for us to listen to the poem again.

The Garden of Gethsemane

by Malika Booker

I cannot tell you what the trees whispered to him that night

air ripe with the scent of living, fruits pungent, leaves

clapping, harmonising with the crickets rhythmic screech.

What could trees whisper to a Black man juggling sorrow

on the eve of his catastrophe, face tortured, back bent

from the weight of prophesy, kneeling in damp soil,

thoughts wrestling. Each worry a serrated knife gorging flesh.

Say he was weeping, beating his chest, murmuring big man

don’t cry, wanting to unshackle from his father’s heirloom

but what Papa does not force their son into a square box,

each corner reinforced with the black tar of hardening expectations.

And the garden was not a tonic. When he spoke to the leaves,

did they not turn their backs, curl into their spine to recede

into their own nourishment, leaving him to keep his own vigil

on this seemingly ordinary night, the eve of his prophesied death.

And those disciples! My soul is exceedingly sorrowful, even

unto death, tarry ye here, and watch with me, he asked them.

Oh those fickle hard ears men, how their snores became bass

in the ripe music of this garden. How they will regret

not catching the tremor in his voice, the slight waver

each pause. Regret will sit heavy on their chests

whenever they remember this garden, and not reading

the nuances, his pathos, between each utterance of his asking.

Sit ye here while I go to pray. Meaning, sit so we can converse

in the language of grief. Meaning, it is my last night with you.

Let us partake in the language of wake, lick down dominos,

and make ole talk, come nah man. Meaning, be my brothers tonight.

Come lick down double six and rock the table, disturb the still

of the night. He wanted ole talk, lime and labrish.

My soul exceedingly sorrowful even unto death.

but his brother’s snores mingled with the owls hoot and the leaves

turned their backs, while his kinfolk sprawl out in sleep.

The nails, the nails

bones breaking, splintering

bearing timber on your back

like a donkey carrying load

Say he is weeping and beating his chest muttering

big man don’t cry, Mourning his lack of ordinariness.

Mourning his body will not rot, worm and decay.

Maggots will not feed on his flesh.

Now his palms dig into the soil, earth in fingernails

shifting the dirt, man’s flesh is moulded from, burying

this sorrowful weight, then standing as the stuttering

light of morning approaches.

Pepper Seed

Malika Booker’s latest collection is Pepper Seed, published by Peepal Tree Press.

Pepper Seed is available from:

The publisher: Peepal Tree Press

Malika Booker

Malika Booker is a poetry Lecturer at Manchester University, and a British poet and theatre maker of Guyanese and Grenadian Parentage. She is the founder of Malika’s Poetry Kitchen, a writing collective, which has met for over twenty years and creates a space for marginalised voices to develop their craft. Her first poetry collection Pepper Seed (Peepal Tree Press, 2013) was shortlisted for the OCM Bocas Prize and the Seamus Heaney Centre Prize (2014) for first full collection. She is published with the poets Sharon Olds and Warsan Shirein The Penguin Modern Poets Series 3: Your Family: Your Body (2017). Malika is a Cave Canem Fellow, and in 2020 she won The Forward Poetry Prize for Best Single Poem.

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

The Garden of Gethsemane by Malika Booker

Episode 25 The Garden of Gethsemane by Malika Booker Malika Booker reads ‘The Garden of Gethsemane’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.Malika Booker's latest collection:Available from: Pepper Seed is available from: The publisher: Peepal Tree Press...

Humming-bird by D. H. Lawrence

Episode 24 Humming-bird by D. H. Lawrence Mark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘Humming-bird’ by D. H. Lawrence.Poet D. H. LawrenceReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessHumming-bird by D. H. Lawrence I can imagine, in some otherworldPrimeval-dumb, far backIn that...

Nothing the hedgerows say by Mark Antony Owen

Episode 23 Nothing the hedgerows say by Mark Antony Owen Mark Antony Owen reads ‘Nothing the hedgerows say’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: Subruria by Mark Antony OwenAvailable at: Subruria.com Nothing the hedgerows say by...

The post The Garden of Gethsemane by Malika Booker appeared first on A Mouthful of Air.

Visit Podcast Website

Visit Podcast Website RSS Podcast Feed

RSS Podcast Feed Subscribe

Subscribe

Add to MyCast

Add to MyCast