Sara Grillo

Keep your clients far away from ESG investing - it's a rip-off!

ESG sucks. In this podcast we’re going to talk about why ESG is a rip-off and nothing more than a way for Wall Street to earn higher fees off unsuspecting people who mean well. Don’t let your clients get taken! Listen to this show.

In this podcast we are going to expose the truth about ESG investing. I am joined by Eric Balchunas who is a Senior ETF Analyst at Bloomberg and the author of “The Bogle Effect.” And also Dr. Ellen Quigley, Special Adviser to the Chief Financial Officer (Responsible Investment), University of Cambridge and Senior Research Associate (Climate Risk & Sustainable Finance), Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, University of Cambridge.

For those of you who are new to my blog/podcast, my name is Sara. I am a CFA® charterholder and I used to be a financial advisor. I have a weekly newsletter in which I talk about financial advisor lead generation topics which is best described as “fun and irreverent.” So please subscribe!

ESG Vocab

Before we get into it, let’s start with some basic definitions:

ESG: ESG stands for “Environmental, Social, and Governance” and it’s a style of investing that purports (but does not, in reality) save the world from its evils. Governance is an unhelpful tack on, according to Dr. Quigley, usually viewed as unrelated to the first two related to things like board composition etc.

SRI: Socially Responsible Investing. This is a restrictive type of investing that aims to avoid directing funds into sin investments such as tobacco, etc., through use of screens.

Impact investing: A private investment in a company, made in the spirit of saving the world.

Brown stocks (also called “dirty” or “fossil”) vs. Green stocks. A pure play fossil fuel company would be brown whereas a pure play wind turbine company would be viewed as green.

Reasons why ESG sucks

The following are reasons why we believe that ESG is a bad investment strategy.

1. It’s active investing done badly.

By excluding certain types of stocks, you make it more likely you’ll underperform.

According to an article by Larry Swedroe from 2016, controversial investments yield post abnormal returns, generally, and screening them out causes performance to suffer. Swedroe cites a study by Greg Richey from the Summer 2016 issue of The Journal of Investing. Richey’s research found that found a “Vice Fund” produced a greater risk-adjusted return over the market portfolio (Richey, 2016, as per Swedroe, 2016).

With all the moral propaganda and pulling on the heart strings, it’s easy to overlook that ESG, at its core, is an active management strategy that comes, generally, with higher fees (we’ll get to that later) with performance that doesn’t justify them.

It’s the concept of “slactivism”, according to Balchunas: you want to do something good, but you don’t want to exert too much of an effort.

Dr. Quigley says that it’s like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic, because if you look at the effect that climate change will have on your portfolio overall in the long term, it dwarfs the impact of higher fees anyways, whether or not ESG investing actually works.

2. Secondary market trading doesn’t really impact the company.

The idea that market participants can voluntarily change overarching global problems by the force of their market behavior is a flawed premise that sounds good but doesn’t hold up.

These are key points that many financial advisors do not understand.

First of all, Secondary market trading doesn’t really impact the company. It’s just exchange of shares. Your money goes to a different shareholder. It does not go to Apple’s checking account.

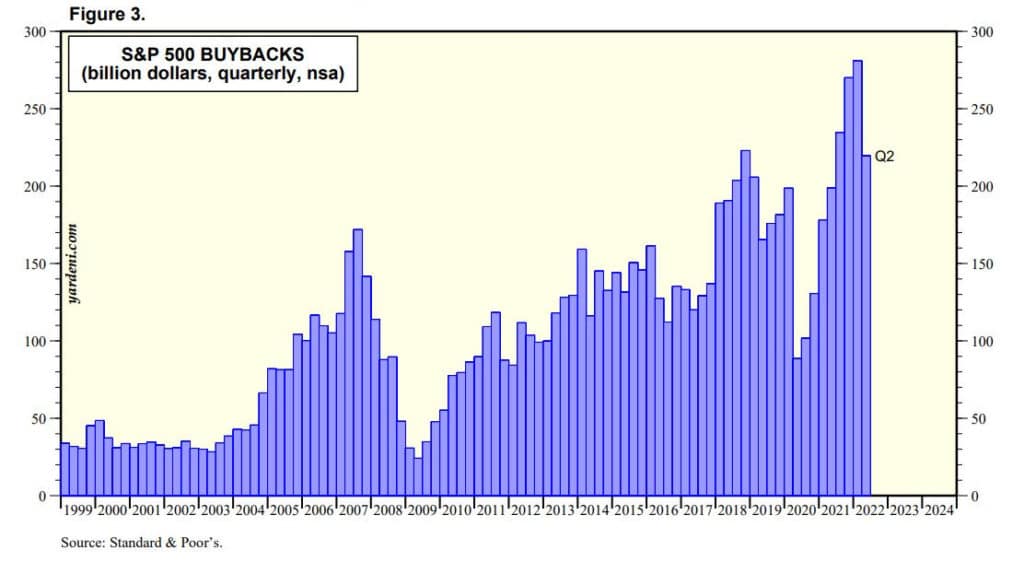

Secondly, The ”bad companies” who are the offenders already have enough capital. They aren’t issuing shares to fund their operations. In fact, they are probably net buyers of shares. The giant companies are sitting on massive cash piles; Apple is sitting on 202bb in cash. According to Yardeni Research, there was $200B of buybacks in Q2 2022 for S&P stocks (which boosts the price).

Source: Standard & Poors, Yardeni

And guess what else!

The massive cash pile held by just 13 companies accounts for nearly 40% of the $2.7 trillion held by all of the companies in the S&P 500. S&P 500 companies now have enough cash to give $8,131 to every man, woman and child in the U.S.

-Investor’s Business Daily, February 3, 2022

Ehem.

Third, share prices dropping doesn’t tick off the executives who hold large amounts of company stock because often their compensation is determined by the number, not price, of shares. If the company were to become delisted from an exchange, or if they are voted out by proxy, the directors may become embarrassed, fear of which may be a bigger motivator of good behavior.

Lastly, markets are competitive and there are certain types of investors who will look at a company with good cash flow selling at a depressed price and buy shares on fundamentals, even if it is a moral offender. The price will rebound. It takes an unrealistic amount of divestment to have a real effect on a company.

According to Dr. Quigley, 90% of capital raising happens through the bond market. That is where the money flowing into fossil fuels comes from. If you are going to have exclusions, the bond side is much more likely to have an effect. Bond issuances, not secondary market trading in public equities, would have an effect. Public traded equity is not new money, unlike bond issuances.

3. ESG signaling and wokeness are destroying corporate America.

Here’s why I hate ESG ratings.

It’s unclear who the good and bad stocks are because ESG scores are just meaningless signaling. There’s no universal meaning. The ratings are assigned by different companies in a way that is too different. It’s not like in the corporate bond market where we have Fitch, Moody’s, and S&P ratings agencies. There is a huge disparity from one to the next in ESG scores. Two examples of companies who assign ESG scores are SASB and Refinitiv.

Also, ESG scoring is nothing more than a funding tool. Companies have to signal that they are “woke” and consistent with progressive values in order to get funding. It’s more an indication of what your CEO tweets about than the actual virtue or vice of the company’s behavior.

This lack of fairness, transparency, objectivity and the ideology the enshrines the offering up of stock market competitiveness as a sacrificial cow of wokeness is yet another reason why ESG sucks.

4. ESG fees are Wall Street ripping off the consumer

Yet another reason why ESG investing is a bad idea – the fees!

Plain old index funds suck for Wall Street because they decimate the fees they get. But by sneaking in active management in the form of ESG, Wall Street gets another crack at shaving off a higher level of fees from the unsuspecting consumer.

Research shows that ESG comes with higher fees, so much so that it may be better to take fee savings and donate it to a charity that has impact than actually invest in an ESG fund and pay the higher fees.

From a Wall Street Journal Article:

The environmental, social, and governance funds’ average fee was 0.2% at the end of 2020, while standard ETFs that invest in U.S. large-cap stocks had a 0.14% fee on average.

-Wursthorn, 2021, as per Sullivan, 2021

Did we convince you that ESG sucks (yet)?

Thanks for reading our blog about the drawbacks of ESG investing. We hope you’ll run in the other direction now that you know the truth about ESG.

I hope you’ll subscribe to my newsletter.

Join our next Transparent Advisor virtual meetup.

These meetups are free and the goal is to learn from each other about how to grow and manage a transparent practice for the benefit of clients.

Even if you can not make the meetup, or even attend in its entirety, please register for the replay and to be notified of the next one.

Learn what to say to prospects on social media messenger apps without sounding like a washing machine salesperson. This e-book contains 47 financial advisor LinkedIn messages, sequences, and scripts, and they are all two sentences or less.

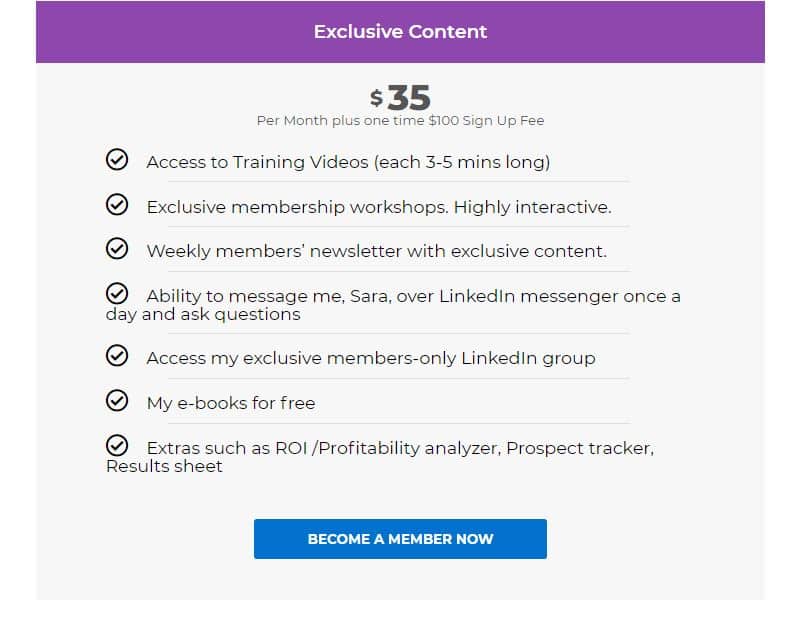

You could also consider my financial advisor social media membership which teaches financial advisors how to get new clients and leads from LinkedIn.

Thanks for reading. I hope you’ll at least join my weekly newsletter about financial advisor lead generation.

See you in the next one!

-Sara G

Sources

Krantz, Matt. (9 February, 2022) Investor’s Business Daily. 13 Firms Hoard $1 Trillion In Cash (We’re Looking At You Big Tech). https://www.investors.com/etfs-and-funds/sectors/sp500-companies-stockpile-1-trillion-cash-investors-want-it/

Richey, Greg. (2016, May). Sin Is In: An Alternative to Socially Responsible Investing.? Journal of Investing, 25(2):136-143. DOI:10.3905/joi.2016.25.2.136. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303634950_Sin_Is_In_An_Alternative_to_Socially_Responsible_Investing

Sullivan, John. (2021, March 16). 401k Specialist. Sustainable Scam: Is ESG About Responsibility or Higher Fees. https://401kspecialistmag.com/sustainable-scam-is-esg-about-responsibility-or-higher-fees/

Swedroe, Larry. (2016, July 25). ETF.com. Swedroe: Costs Of Socially Responsible Investing. https://www.etf.com/sections/index-investor-corner/swedroe-costs-socially-responsible-investing

Wursthorn, Michael, (2021). Wall Street Journal. Tidal Wave of ESG Funds Brings Profit to Wall Street https://www.wsj.com/articles/tidal-wave-of-esg-funds-brings-profit-to-wall-street-11615887004

Yardeni, Dr. Edward, Abbott, Joe, Quintana, Mali. (9 December, 2022). Yardeni Research. Corporate Finance Briefing: S&P 500 Buybacks & Dividends. Figure 3: Buybacks & Dividends. https://www.yardeni.com/pub/buybackdiv.pdf

Podcast transcript

0:00:01.0 : ESG, get the beeeeep out of here. ESG sucks. In this podcast, I am joined by Erik Balchunas, who is a senior ETF analyst at Bloomberg and the author of The Boggle Effect. Dr. Ellen Quigley is a special advisor to the Chief Financial Officer of Responsible Investment at University of Cambridge. She is also a senior research associate in climate risk and sustainable finance at the Center for the Study of Existential Risk at the University of Cambridge. We’re going to talk about why ESG is nothing more than a way for Wall Street to earn higher fees off of unsuspecting people who mean well. Don’t get taken, folks. Listen to this show. Welcome, Erik and Ellen. Thanks so much, Sarah. Great to be here. Great to be here. So what we’re going to do is I’ll list out the reasons I think ESG sucks and then after each one you tell me if you agree or disagree. If I’m tripping or whatever. Sound good, folks? All right. So before we get into it, let’s just start with some basic definitions because one of the things, first of all, that really annoys me about ESG is how some people, even people who are supposed to be the credible authorities, misuse the terminology in this field.

0:01:15.9 : So first of all, ESG, what does each letter stand for? Who wants to take it? Environmental, social, and governance. Okay. And so I think people understand the E and the S a lot, but what is the G part actually? It’s an unhelpful tack on. Usually viewed as unrelated to the first two, but it’s meant to address things like board composition and so on and so forth. Okay. I can tell you’re not a big fan of this. This is going to be good. I’m going to get into it. Okay. Another term that people often blend with ESG is SRI. Now this is way back. I remember, it must have been over a decade ago, Amy Domini with Domini Investments was one of the first kind of socially responsible investors. So SRI stands for socially responsible investing. Is it ESG? It’s useless in many of the same ways, but probably with much more sincere intentions behind it. Well, socially responsible investing aims to eliminate the sinners. So, you know, gun stocks, nukes, whatever. So it’s a restrictive form of investing and it is a part of ESG, but people kind of use it interchangeably and it’s not. Okay.

0:02:34.8 : ESG is not all involving restricting from the bad investments. ESG also aims to promote supposedly the goal of ESG is to promote the growth of companies that are supportive of beneficial practices, which is debatable and we’re going to get to that. Impact investing. Okay. So impact investing is, well, in some cases it refers to making private investments or investments in private companies, but it’s the idea of promoting companies that aim to do good in the world or have an impact. Brown versus green stocks. Could we say dirty or fossil instead of brown? Sure. Yes, exactly. This is something that people just throw around. So what’s the distinction there, Ellen? I mean, it’s going to sound a bit artificial, but yeah, so like a pure play fossil fuel company would probably count as a dirty or fossil fuel stock, whereas a pure play wind turbine company would be viewed as green.

0:03:36.1 : Okay. And right there, I think, you know, the idea of, okay, well, first of all, my take on impact is I’m probably the most optimistic there. I don’t know how Ellen feels, but impact is, okay, let me buy wind turbine companies or solar energy companies. And in the ETF side, those ETFs would be like tan, which is like 20 solar stocks. It’s a pretty clean situation or communication. Hey, I want to put my money into some things that where people get up every day and try to like get something done on this thing. That’s just the E by the way, it’s not the S and the G, but that kind of makes sense to me. I’m going to put my money towards this and try to have an impact. So when you talk about those companies, that kind of play also typically fits in a portfolio where you might have like a couple of cheap index funds or your 401k account. You could just tack that on. You know, 7, 8% or even less. And now you are sort of long these stocks or companies that are doing this thing that is good for the environment or what have you.

0:04:48.1 : I’m sure we’re going to get to the ESG and SRI where you exclude companies, but I kind of get impact investing. To me, that makes sense. I think people sometimes confuse that when Tesla was kicked out of the S&P 500 ESG index, people were like, what? It’s a clearly, it’s literally an EV company, but people, again, they confuse what the company does with their ESG scores. Whereas impact, I think is a little clearer. What this company does is part of the impact. And I just seems like it’s the communication there at least is pretty clear. I don’t know if you guys disagree, but impact to me makes the most sense.

0:05:28.2 : I think we do disagree on a couple of things, Eric, which is good because it’ll keep Sarah’s podcast interesting, but I would not consider a renewables ETF an impact investing and would, it’s pretty much useless to select that versus something else because it’s secondary marketing. Okay. But let’s go through that. Like, so if you buy 20 solar stocks, why is that useless?

0:05:52.0 : Because there’s no additionality base, not, not, no, there is such a tiny, tiny amount of additionality that it’s basically, it’s, it’s basically no additionality. So it’s secondary market. It doesn’t affect the company. You’re buying and selling between and among investors. The money doesn’t go back to the company. I’ve reviewed all of the studies on this. Basically, it’s hard to find any real impact from that.

0:06:14.3 : What about if you just think that’s a, an industry that will, will grow?

0:06:21.8 : Sure. But then you’re not having an impact.

0:06:23.8 : Okay. All right. All right. Fair enough. Maybe I’m confusing the fact that impact has to be private. Does it have to be in the private markets?

0:06:33.3 : Sarah, feel free to, I know I have to say the whole thing about it. I think it has to be in debt or, or private markets because that it has to be a primary market transaction.

0:06:45.6 : Yeah. Right. Okay. I mean, let’s face it though. I mean, enough public market interest could push the envelope on some of these things, but if, if my little account buys tan, I, yeah, it’s not going to really move the envelope. Even at high. Yeah. No, like honestly, it’s, it’s secondary market is not where we want to have impact even at fairly high levels of involvement on the part of very large investors. So, okay.

0:07:12.0 : Let’s just say we, okay. I still get impact investing if it’s private, right? I’m not saying I don’t, I think what I will then switch my terminology, I’ll call tan a thematic ETF that happens to be in the sort of environmental realm. And I, I like those. I mean, I, I, again, I’m kind of with you. How much good does it do? How much good does it do? But for me, I’m looking at portfolios all day and I, to me, there is a, you could see the practical purpose. I mean, let’s just say, is there any purpose at all to owning a solar company?

0:07:48.7 : I mean, yes, but I mean, yeah, we could, this is a whole conversation. It’s just that like owning a listed solar company, owning the shares of it doesn’t help or hurt that solar company on average.

0:08:02.8 : Right. And I think this is where we get into the ESG and which is a bigger that, you know, ESG wants to sort of be your core, right? Wants to be, hey, sell all your index funds and buy this ESG strategy. And then the question is how much does that actually impact these companies? I would assume you’re of the no, because now we’re talking the same deal. It’s all secondary market. It’s all publicly traded companies. I’m going to value this one and take this one out, tweak this, do that. And I’ve got my ESG. I’m going to sleep at night. And that’s, that’s largely BS.

0:08:39.6 : Yeah. It’s rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

0:08:43.4 : Yeah. This is what the BlackRock X sustainability person came out and basically said, not only is it not doing anything, it’s actually bad because it’s giving people a false sense of I’m doing something.

0:08:55.8 : I really agree with Tariq on this. He’s technically right. So what I have about five reasons that ESG sucks. And one of the reasons is, and folks tell me if you agree or not with this, is that it’s active investing done badly. And the reason is that by excluding stocks, you’ll make it more likely that you’ll underperform. According to Larry Swedro, quote, controversial investments generally yield positive abnormal or risk adjusted returns using the Carhartt, Carhartt four factor model, which is beta size value and momentum. Screening them out produces suboptimal financial performance. Practically all controversial cluster portfolios significantly outperform the market and do so with statistical significance at the 5% level. And in most cases at the 1% level. Gray Ritchie summer in the 2016 issue of the Journal of Investing, Ritchie examined the risk adjusted returns of a portfolio constructed of firms from SIN or vice related industries using data from the Center for Research in Securities prices covering the period May 1995 to May 2015. He analyzed the performance of a vice portfolio made up of 41 corporations against the market portfolio. The firms in his vice portfolio came out, sorry, came from the alcohol, tobacco and gambling industries listed on the nice NASDAQ or NASDAQ OTC.

0:10:27.5 : He then added firms in the defense industry to complete the portfolio of vice stocks. Ritchie found that the vice fund produced a greater risk adjusted return compared to the results of the Carhartt four factor model over the market portfolio throughout the same period. The results were statistically significant at the 5% confidence level. What do you think?

0:10:50.3 : So I completely agree. Larry Swedro is really smart and he’s really good at factors and the whole like trying to discern where returns come from. I think also just you’d have to use the sniff test. I’m a big sniff test guy. If you have the ability to buy a sort of Vanguard total market index fund at three basis points fee, that’s a frictionless exposure to everything. And we know sometimes sectors have good runs, then they go down, they go up, they go down. Growth is in play, value is in play. We just saw it this year. Many ESG ETFs are underperforming because they tend to have a little bit of a tilt towards tech, which has high ESG scores and a little bit tilt towards growth. Those two are out of favor. The dirty oil stocks are having a great run and that’s been tough on them. So this year I think has reminded people that you’re right, it’s an active strategy. In a book I just wrote, I talk about how active is evolving. And one of the new ways is ESG. I find that’s like, active has a lot of faces and this is a new face of active.

0:11:53.1 : But they try to pull at your heart strings and your morals. And that’s what I find a little dangerous because it’s sort of pitched as you’re going to sleep at night and outperform and do good. And maybe you’ll sleep at night and maybe you’ll sleep at night, but the other two, we don’t know. You might outperform during a couple of years, then you’ll underperform. But over time it’s going to be higher fees. So I would argue if you took a Vanguard three basis point, classic index fund and you compared it versus an ESG fund that maybe costs, let’s say, we’ll be generous, 20 basis points only. Over 10, 20 years, I’d be very confident that the Vanguard one wins. The question some people are now asking is, well, is the underperformance worth it? And that’s where I don’t even think it’s worth it. So I’m not really sure. In my opinion, a lot of this is A, active and B, preying on slacktivism, which is the idea that I want to do good, but I don’t really want to make a lot of effort. I just want to feel like I’m doing something good and then I can go on my way and not, I don’t actually really care to look into whether it is actually doing good.

0:13:03.9 : I just want the feeling, thank you, and maybe a little superiority and I’m good. And I’ll pay an extra 10 basis points for that. So I worry there’s a lot of that. So I always tell the ESG people, I’m not totally anti ESG. I’m just anti nasty surprise. And I feel like over 10, 20 years, it’s possible somebody wakes up and goes, wow, I didn’t think I would underperform in this thing. Now I’m sad. I sold out my whole core index fund and replaced it with this ESG thing. I shouldn’t have done that.

0:13:32.8 : So some people say that ESG has saved active management because you can charge fees for it. I mean, you’d be very lucky to get away with just a 10 basis point increase to your fee levels from ESG. It’s often a lot more expensive than that. Honestly, the studies are all over the place about SynStock’s ESG outperformance. I think there are methodological issues with many of the studies and there are many different things going on. So one thing is if you look at fossil fuels, for example, they’re a very volatile sector. And so I’ve reviewed 118 years worth of data in all the studies that I looked at. And basically, it doesn’t matter whether you own fossil fuels or not, but it really matters when you divest or buy because the timing is hugely significant. I think actually somewhat the same thing is true. I think tobacco and alcohol, if you look at more recent years, the younger generation is not getting into those habits at the same level as others have. And so the most recent studies on tobacco, for example, don’t find the same outperformance. But again, all of that is beside the point. It doesn’t matter.

0:14:50.7 : It’s all, again, rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic because if you look at climate change, for example, the effect that climate change will have on your whole portfolio definitely dwarfs whatever fee levels or stock picking variation you’ll have from the index. So that’s why we have to actually try to address climate change. That would have a much better effect on your performance in the medium and long term than anything else. We can get into what I would suggest to help make that happen through investments, but basically it’s not through stock picking and you will just pay more as Eric was saying. All right. So the second point that we’ve kind of tossed around, and I want to just go back over this so that it’s really ingrained, all right. But it’s the idea of secondary market trading as having impact or being hurtful to the company. All right. And this is what I feel isn’t made clear when you see ESG marketed to investors and even to financial advisors. And I feel like a lot of financial advisors don’t even understand why not. Okay. So the idea that market participants can voluntarily change overarching global problems by the force of their market behavior is a flawed premise for the reasons that we’re going to describe.

0:16:12.5 : Okay. Secondary market trading doesn’t really impact the company. It’s an exchange of shares. The bad companies who are the offenders already have enough capital. All right. And they aren’t issuing shares. In the case of the S&P, a lot of times they aren’t issuing shares to fund their operations. In fact, they’re probably net buyers of shares. Okay. So according to Yardini Research, there was $200 billion of buybacks in quarter two, 2002 for S&P stocks. Okay. And Apple is sitting on over $200 billion in cash. Okay. There’s just a massive cash pile held by these companies. And if they need to boost their price back up, they can buy back stock. Basically, the stock market, you can think of it as like when someone lists, when a company lists on the stock market in the first place, it gets money. That helps because that’s a primary market transaction. But after that point, it’s just a bunch of swirling or it’s trading slash arguably gambling. And there’s no kind of… The publicly listed companies are actually usually returning money to shareholders. Yeah. Well, dividends or…

0:17:23.2 : Well, I would say that returning of the money is why you invest. I mean, that is… Well, yeah. That’s… I mean, forget ESG. That’s like why you want to be in stocks versus a commodity. There is that cash flow that you get a part of. So I agree. That’s a good thing for most people though. But in the case of ESG, that doesn’t matter.

0:17:46.6 : Yeah. But those same companies and many private companies and nationally owned oil companies and so on and so forth will be raising new money on the bond market. And that’s where 90% approximately of new capital flowing into fossil fuels comes from, for example. So if you’re going to have exclusions, the bond side is much more likely to have an effect. And indeed, there is evidence to suggest that that is the case. It has already affected cost of capital on the debt side. And if you have less demand on the debt side, you can raise less money and less of a good price. Whereas it’s just not like that with public equity because that’s not new money when you invest.

0:18:31.3 : Yeah. I like to sometimes imagine the stock market is a circle. It’s just a circle of people trading back and forth. And I think sometimes people need a visual, but that’s all it is. It’s just people going back and forth trading, which is why investment returns, the cash flow and the earnings growth is great. You get that over time. But the trading creates these little bubbles and it comes down. And I think that’s where sometimes in the past five years, the ESG strategy has done well simply because people value tech and growth wasn’t necessarily because of ESG. But again, that’s just speculative return that is very volatile and goes up and down. But it is gambling, although within the stock market, those people trading back and forth in a circle, there are plenty of people who are just in the market and not trading. Those would be investors. But the people who determine the prices are the people speculating.

0:19:32.0 : Totally agree. But if the shares get dumped, if all the ESG investors said, okay, let’s dump all shares of Exxon and the price plummeted, that would have the effect, though, of ticking off the executives who own that company’s stock on a personal level. So even there, it might not, because actually a majority of, especially in the US, the majority of the remuneration packages for executives are actually negotiated on the basis of the number of shares. So if the share price is actually artificially depressed, arguably, the executives are actually better off because they have under priced shares they can sell for. Anyway, so it’s actually, even there, I wouldn’t necessarily argue that you’re going to have a direct impact. And actually, yeah. Well, I would say, like, if there’s a lot of factor investors like Larry Swedroe and a bunch of them who really don’t care about any of this, and they’d love to buy up these cheap shares of an energy company based on their cash flow and their fundamentals being pretty sound.

0:20:43.4 : So you get to get a good amount of cash flow for a cheap price. Somebody is going to buy that. So it’ll probably just come right back up to where there’s an equilibrium. I agree. And even if like the, there’ve been some models that look at just really, really high levels of public equity divestment, and it takes an awful lot of that. I would say probably an unrealistic amount of that to really have an effect on a company anyway. But I agree, people come back in because it’s, and also Exxon’s huge. They’re so huge. There is one thing I heard. I was going to say, I was on a panel with the guy who runs the S&P 500 ESG index. And we were talking about this idea when, you know, they kicked Tesla off. It was a whole controversy. Even, you know, Elon weighed in, called ESG a scam. He was all, and then the companies that were in the index were like Pepsi and Exxon and everybody’s confused and it’s a whole mess. Anyway, on the panel, I was like, what good does this really even do? He did, here’s one case he did make there.

0:21:41.8 : He goes, we’re S&P. These companies want to be in our index and privately they will, they will, we do indirectly or indirectly put pressure on them to fix some of these metrics, simply because they don’t want the embarrassment of getting kicked out of such a, first of all, the ESG index. And that potentially, if they were to get sold off more, they get kicked out of the regular S&P. So there is some like, I want to be in the S&P membership club thing. I don’t know if you, I’m curious to get Ellen’s take on that.

0:22:15.8 : There are a couple of studies that support you actually. I think it does have more to do with kind of social discourse and the index effect. But yeah, that’s, there is some, some evidence to suggest that companies that are threatened with exclusion from an index are more likely to comply with the S&P. Exclusion from an index are more likely to comply with the standard of the index, comma, however, if you look at the data providers in the space, I mean, there’ve been lots of studies about how they disagree. They all measure different things. It’s a mess. But also like most of the stuff that they’re asking these companies to do well at have to do with disclosure only, or other kind of what I call means-based indicators. And if you look at the evidence around disclosure, it’s, there are more studies finding a negative correlation between improved environmental disclosure and actual environmental performance. Then there are studies suggesting that there’s a positive correlation, meaning much of the time it doesn’t actually help the company become any better when they disclose more. But often it’s the companies that want to distract from their really bad emissions by disclosing that are the ones doing the better disclosure.

0:23:25.6 : And again, none of this changes the actual emissions. The planet doesn’t care whether your disclosure is good.

0:23:31.1 : Right. And this is the greenwashing that happens, right? With that. And then there was an article on Bloomberg, which got into this a little bit, which I’m just curious to get your reaction is like, they were saying that even the companies that are the polluters that you want to see do better, a lot of them are just buying credits or somehow they’re not actually not, they’re not actually changing their behavior. They’re just financing their way around it. But the, that does have a downstream impact because it, those credits or that money goes to a solar company or somebody who is doing that kind of a thing. So there is a downstream positive impact, but the company got its ESG score up without really doing anything.

0:24:20.5 : So it’s actually even worse than what you say because offsets, for example, there’s a study that suggests that about 95% of offsets do not sequester the carbon promised. And in general, I’m very skeptical of that field. So having companies meet these commitments through offsetting or credits, I don’t think that’s credible. Also, I mean, as, you know, Oliver Hart and Luigi Vingales have written, there’s a comparative advantage for companies in preventing externalities from costing society in the first place. Like to try to clean this stuff up afterwards doesn’t make any sense if you can prevent it from happening in the first place. The prevention, you know, pound of cure, all that, all of the sayings on this ring true. It’s going to be just a point for the audience. What is an offset? So it’s basically like a religious indulgence, effectively. So if you emit a ton of carbon, you can pay somebody else to hypothetically sequester or reduce the equivalent in their own emissions. And the problem is, is that, I mean, a lot of these are, yeah, anyway, this could be a whole other episode, Sarah, actually. But basically, it’s a way of not having to actually decrease your own emissions, but instead getting someone else to do it, supposedly, which is kind of the problem.

0:25:44.7 : There are, you know, carbon credit schemes that are, like there’s one in the EU and so on and so forth. Like it depends on who does it and what it is. But in general, the whole idea of offsets in particular, quite problematic. And yeah, probably better to actually be emissions at source. But to me, this adds only another layer of confusion and ineffectiveness. Because even if you got the right ESG ETF that you just can live with and sleep at night and all that jazz, some of the companies that make it in probably do this number. So the greenwashing underneath the fund is a whole nother layer that most regular people cannot go that deep into due diligence and figure this out. I mean, I guess if you follow like certain like green publications, maybe they’re going to talk about this a little bit. But again, the vast majority of people that ESG is being pitched to are regular people and advisors who are just have that feeling like I want to be that person who has the green portfolio and I can, you know, not be investing in the bad people and the bad things.

0:26:57.6 : And it’s pitched so simply. But again, you unpack this and it’s layer upon layer of like inconsistencies, confusion, lack of transparency. Also, the ESG industry also does itself no favor because we talked about the E, the S and the G. And the things that make up the E and the S and the G, there’s maybe, I don’t know, 15 metrics under each give or take. They never get explained to normal people. The ESG people don’t really do a good job. And so a regular person has an image of a company like Tesla and thinks this has to be an ESG company. It’s out there making cars. But the scores are much more detailed and wide ranging than just what the company does. Right. So right. There’s so many levels. That’s what I wanted to get into next. That was my third reason. This is this is another thing is that ESG ratings are just a form of signaling. And a lot of times they’re quite insubstantial. So it’s unclear who the good and the bad stocks are because ESG scores are just signaling. There’s no universal meaning that has anything true behind it. OK, the ratings are assigned by different rating companies.

0:28:14.5 : It’s not regulated. And they’re all different from one to the next and how they evaluate these companies. It’s not like in the corporate bond market where we have Fitch and Moody’s and S&P. Right. There’s this huge disparity between how one rating agency is doing it and the next one. So, I mean, none of it matters is the problem. Right. Like, we’re spending a lot of time on these disagreeing ratings. Yes, they disagree. Yes, they measure irrelevant things, in my view, for the most part. Again, it tends to be like indicators of indicators, reporting and disclosure instead of actual impact. But none of that matters because the ratings are typically applied only to public equity holdings anyway. So it’s all like it’s rearranging of deck chairs on the deck of another deck of another deck. Like it’s just it’s uselessness piled on top of more uselessness. Oh, man, I honestly I thought I was the most like the biggest skeptic. I’ve met my hero. I think this takes the whole conversation and just makes it almost an exercise in futility. This public compass, you know, if you’re on the secondary market, you might as well just not bother.

0:29:30.8 : I mean, there are other things to do.

0:29:33.3 : There are other things you can do. I do have some hope. But yeah, you’re right. I am usually the most skeptical person in the room.

0:29:39.7 : I mean, it’s funny where you talked about impact and going to primary market. I’d love to get your take on this one thing that this against I’m more sniff test. I’m not an ESG person, but I have to cover it because I cover ETF. So I don’t know four to 3% of my world is ESG, right? But when I go to ESG, it’s be taken up a little more of my time because it’s such a debatable issue. And there’s so much hype and I have to push back against it. So I’ve heard about it a lot. But one thing I’ve come to some conclusion of is naturally is what you did, which is I don’t know how much you can actually do good with your portfolio. It seems like the way to do this is through the government like voting and regulation. And as a consumer, it seems like you have way more power as a voter and a consumer than you do as an investor. But the investing seems to be a place where it can be expedited. You could get more fees there. So they’ve really grabbed onto this lane as a way to change.

0:30:40.2 : But it just seems like the weakest lane of the other choices. What do you think of that?

0:30:45.8 : I think that it can ease ahead of consumer behavior pretty easily actually for reasons we can get into if that’s helpful, but not the way it’s currently being done at all. So there are other things that can be done as an investor because there are… So actually, I mean, I agree with you about voting and regulation, huge, comma, however. All of that whole process… So I’m Canadian, right? And we’ve got intense fossil fuel capture of policymaking in my country. And that is actually something that is within the control of large institutional investors because it’s these companies that are doing that lobbying directly or through trade associations. So that’s one aspect. That’s something that could very concretely be done to help improve the political process and the outcomes associated with it. So that’s huge. But also, I’m more of a subscriber to the view of universal owners. So basically everybody now these days, other than the speculators we were talking about before, own a more or less representative slice of the whole economy. And therefore, you have to think about externalities. You have to think about things that some companies are doing in your portfolio that are hurting everything else.

0:32:06.7 : And part of the problem is that many of the companies that have the greatest externalities, the greatest that impose the greatest costs on everything else in your portfolio, are domiciled in a country that may not want to regulate that because it’s pretty profitable. But if you own, if you’ve got investors from around the world who can force behavior change, that’s a way of kind of leveling the playing field across jurisdictions and therefore supporting the kind of regulation that we would want to see too. Because if you can get enough behavior change from the company in the reluctant country, then that company might actually want its smaller competitors to actually be regulated to meet the same standard that they’ve been forced to achieve through investor pressure. So that’s part of the theory. It’s all an assemblage though. You do need the, I mean, there’s probably nothing more important than government regulation and your influence over that by voting. And then the other thing about consumption, I’ve had ESG people before say that’s just not really that big of a deal.

0:33:09.7 : But I think to normal people who look at ESG and then they, or they see somebody talking about climate change, you may even believe in climate change, but you’re just unable to change anything about your lifestyle that’s inconvenient. And even like very wealthy climate change advocates just fly on private jets and there doesn’t seem to be any inconvenient choices being made. And it seems like inconvenient choices are absolutely necessary and would get more followers than just talking. But maybe I’m wrong. Maybe the talking and there’s just one or two switches that can be flipped all of a sudden. But I’ve always thought that if you want to make Exxon ESG just demand green energy, like the demand will, supply will react to demand. And sometimes I feel like ESG is trying to force supply to change demand, but demand is clearly, if you can’t change demand, what’s the point of messing with supply?

0:34:11.5 : So I think that’s a very logical train of thought, but there’s a reason that the fossil fuel companies actually funded the whole carbon footprinting exercise. And it’s because they know that actually without system change, individual behavior change is really, really hard. So there’s actually no credible way to demand green energy in your home, because usually that’s difficult to do, maybe even impossible, and especially to get kind of additional demand from consumers. And the fossil fuel companies understood that very well, right? Like if I want to take only public transport, I need there to be good public transport. Like it doesn’t actually, the connection between even quite a few people deciding to take more public transport, that’s not going to make the difference. What does make the difference there is governments actually supporting investment in public transport. I do think if you’re Al Gore and you’re flying around in your private jet, yeah, you should make a different choice and it is going to probably be more inconvenient because that’s an outsize effect on overall emissions. And again, the rich are actually very disproportionately contributing to emissions anyway. But for the average person, what’s going to be much more effective is to work on voting and then to pressure pension funds and banks with whom you have a direct relationship, because those are the big blocks of capital that can actually push companies.

0:35:35.5 : But how much does the whole economy have to change? Because aren’t the rich really the ones rich now, rich because of globalization and like everybody moving all over all the time and stuff being shipped and everything just flying all over the place. Whereas, like remember during the pandemic where people like just stayed home and walked down the street and everything just came to a standstill. And I had this feeling like this might be what has to happen. Like globalization will have to resort to localization because you can’t just send everything everywhere all the time, right? Or is the proposal to make everything you’re sending and moving and flying and this all somehow green and not having an impact on the atmosphere?

0:36:20.1 : I think that’s a really, really interesting question. I think one of the disturbing things about what we saw in the pandemic is that even with, I mean, it’s like the ultimate experiment in consumer choice, except for that people didn’t choose it, but no one knew basically for a while. And it only cut down emissions and demand for oil by a relatively modest amount, because it’s the system, right? Moving things around still accounts for a huge percentage of overall demand for oil. And gas is built into lots of our systems, heating homes and electricity. These things aren’t things that individuals can shift, even with the most extreme example of everybody staying home for quite a long time. So yeah, that just seems like… But the interesting thing actually is that as we move away from fossil fuels, we will de facto be localizing our economies more, because I mean, most oil and gas are exported and therefore imported, whereas with renewables, that’s really not the case. It’s something like 3% of renewables get exported across the border, whereas it’s like two thirds for oil and gas. So yeah, I think it’s an interesting thought exercise, but we will see de facto less movement of at least some goods, just as an automatic response to the penetration of renewables into the system.

0:37:53.3 : Then there’s also the idea of companies engaging in ESG just for the purposes of virtue signaling, so that they can get their ESG scores up. So in a sense, the companies that are the subject of ESG are trying to game the system, and they do. Completely agree. What’s the signal if most of the indicators are, are you reporting this, are you disclosing this? It actually gives a roadmap for anybody who wants to game the system to do so. They’re very happy to produce a report and not do anything else. If you go on Twitter and you just see the CEOs tweeting things like…

0:38:32.8 : The signaling thing you talked about, that’s where the CEO comes out for or against something. Again, that’s probably slacktivism. That’s just someone trying to say, I’m a good person. I’m into this issue. There’s actually ETF that came out here called Yall, the God Bless America ETF, which purposely, it invested in the market, but it takes those companies out if the CEO does anything that’s virtue signaling, which is… That’s how many ETFs there are. There’s an ETF that’s called God Bless America. That’s how many ETFs there are. There’s an ETF that does that.

0:39:03.3 : Yep. There’s starting to be some scrutiny of these types of claims though. That’s the good news. In the UK, HSBC has been pulled up because they’ve been advertising their green stuff, but of course, they’re one of the world’s largest financer of fossil fuels. Similarly, in Canada, RBC, also one of the world’s largest financer of fossil fuels has been pulled up for its green advertising. Because it is misleading, but finally, we’re starting to see that that signaling sometimes have some negative consequences if it doesn’t match reality, which it pretty much always doesn’t.

0:39:39.9 : The G. We’ve talked about the E a lot. The G is about this governance thing. I was exploring this for Warren Buffett, because they really value independent directors on a board, which makes sense. You want an independent… But he says, I have been on 20 public company corporate boards, and I’ve seen a lot of them operate, and the independent directors in many cases are the least independent. If the income you receive as a corporate director, which typically may be around 250,000 a year, that’s an important part of your income, and you hope to get on some other boards, and then the CEO calls and says, how so and so, and the current CEO, your CEO says, oh, he’s fine, he never raises any problems, then you’re likely to get on another board for another 250K. How in the world is that independent? Because Berkshire sucks in the G, and they are not in any ESG ETFs. People find that shocking too. They’re like, Warren Buffett, he’s a big philanthropist. He also sticks to the E, by the way. The E too. I get it. The E as well. But the G, he brings up again another point that makes you think.

0:40:50.7 : Look, this actually links to some of the positive stuff that comes out of the research in this area.

0:40:56.9 : So I’m not saying this is a silver bullet at all, but there is some evidence to suggest that voting against the re-election of directors, like retaining the shares of a company you disagree with, voting against the re-election of directors, it’s actually pretty embarrassing for somebody who’s got that dynamic going on behind the scenes. These are high status individuals, even if they get 90% of the vote, that’s a slap in the face often. So combining that with denying primary market capital to the same company, you can have that kind of personal embarrassment element plus potential effect on cost of capital, and together those could plausibly actually have an influence on a company. And again, the other thing that you kind of end up concluding in this space is that we need a diversity of different tactics, and it’s the kind of assemblage of them that’s most likely to produce a result. And that’s what you see if you look at examples like apartheid South Africa, and so on and so forth. It was like layering on of a bunch of tactics. And I think we have to use the strongest tactics that we’ve got, and those appear to be voting against the re-election of directors and denying primary market capital like bond money for a new bond issue.

0:42:06.6 : So you’re bringing up voting, and this is where there’s two dimensions to this argument. There’s an ESG fund that picks stocks based on these metrics, right? That’s a whole thing. That’s investing ESG. Then there’s, that’s the what? That’s the Titanic.

0:42:23.1 : Yeah, that’s the Titanic. That’s the Titanic.

0:42:25.7 : What about this, though? What about you’ve got Vanguard BlackRock, State Street, own about 20% of every American company, the way they vote their shares and how much impact does that actually have? Because there’s a company called Engine Number One, which says, here’s how we’re going to do it. We’re going to just serve you beta. So we’ll hold all the stocks, but we’re going to be activists and push for these things and try to get in the ear of these bigger investors. And they had some success with Exxon. And then that’s how they’re going to do it. And that’s more the proxy voting method. Would you find that to be less Titanic-ish? Yep. Yep. With a couple of caveats. So, I mean, one is like, I do, I would personally, if I had any money, I would probably personally invest in index funds, but I would be very careful about which company I went with. And I definitely wouldn’t go with any of the top three that you just mentioned because their voting records are poor and they are primary market purchasers of all sorts of things we wouldn’t want. But I think it’s much more credible to just track the market and then be much more aggressive.

0:43:31.8 : Shareholder resolutions, though, definitely don’t vote against them because I actually feel like that could hold back progress. But shareholder resolutions, I think, are more of like a longer-term social discourse thing, more so than directly immediately effective because most of them are disclosure-based only, as we’ve been discussing. Most still don’t pass. And then even if they pass, the implementation rate is actually quite poor. And again, if you’re just implementing write a report, that’s not very useful anyway. So I’m a little bit more skeptical of shareholder resolutions unless there’s a lot going on behind them, which I have seen good examples of that, but very few. Because it’s funny, just one thing on this. It’s crazy, BlackRock to me is probably the best example. Vanguard doesn’t say much, so nobody bothers them that much, even though they’re a bigger owner of most stocks. But BlackRock, like Larry Fink came out and said, oh, we’re serious about climate change. But then it kind of threw him into the middle of this. And what’s crazy, BlackRock will have protests outside of their office with climate activists on Monday. And then on Tuesday, it’s coal miners who are pissed off at them.

0:44:46.8 : Or it’s like Florida and Louisiana divesting their pension funds from anything BlackRock-related. And so they get hit from the left and the right. And they put themselves in that position by sort of going into this situation. But I do have some sympathy for how difficult it must be to be one of these companies. So what they started to do, and I think this is probably smart, maybe Ellen disagrees, at least from, if I was them, I’d probably do this. They’re going to turn over or give you an option as an investor in their index funds to either, I believe you could use a third party. And you can pick from, I guess, a couple third parties who might be consistent with your belief system. Because there’s no way they can vote on all these resolutions. They’re too complicated and time consuming. Nobody would do this. No, but no one votes proxies. Right. So Schwab is going to poll the investors and figure out where their head is on these issues and then vote accordingly. But at least giving the end investor a choice of like, OK, BlackRock, I trust you vote how you want or I’ll use this third party.

0:45:54.2 : I don’t know. They’re taking some initial early steps in that direction. I get why they do it. This would probably take a little heat off of them because they could say, well, I’m not doing the voting. It’s my 30 million investors. But then you’ve got all these different views who might actually just end up in the same spot BlackRock is, which is we’re going to be middle of the road and not try to piss off anybody.

0:46:16.4 : There’s a lot in there. So one thing is coal miners should not be mad at BlackRock because they’ve only excluded 18 coal companies out of hundreds and only from their active business when they’re much more a passive house. They’re not hurting coal miners. I find it quite funny that they’ve gotten this anti-ESG blowback for basically doing nothing. And basically the reason that they get picked on too is because they do have a kind of hypocritical approach to this. Sorry to put it that way. Talking a big game but not matching it with what they actually do. I am very skeptical of the voting choice move that they’ve made. I agree with you that it probably makes sense for them to do it, but I much prefer the polling of beneficiaries approach. The way that if you look at behavioral psychology, behavioral finance, people go with defaults to such a degree that you’re just not going to get a lot of opt-in preferences. And therefore what BlackRock does as a house will still account for the vast majority of votes, but there will be less pressure on them to actually vote appropriately with that market power.

0:47:37.9 : So I much prefer the option of polling beneficiaries and voting accordingly. Also, I think it’s more democratic generally.

0:47:46.2 : Yeah, I agree with you. I think polling is where I land. That’s the Schwab method. Vanguard and BlackRock, it’s not quite the same, but I think they’re experimenting. I think one of these will take root. Maybe the polling method will. But I think this is the direction it’s going. Right or wrong? I think the one thing that I think most people… I cover passive investing, and there’s all these passive attacks like it’s ruining fundamental, it’s doing this and that. And most of them are just like sour grapes from active managers. But the one that I thought had the biggest resonance is this, which most people can just understand is like the concentration of power with BlackRock and Vanguard in particular, they each own 15%. And at the rate the flows are going, they’re going to own 20, 30% of most of America’s companies in the next decade, because they take in about two thirds of all the new cash invested in America. And so they’re going to be hugely influenced unless they get regulated and the government just says, you cannot get any bigger, which is possible. But anyway, that point is, so there’s a corporate governance group that sits in New York that works for BlackRock.

0:48:58.1 : Let’s just say there’s 10 people. I don’t know exactly how many others. There’s 10 people. They don’t own that much of any company. It’s 30 million people who own 8% of Exxon. But those 10 people are able to make that vote. I get why that seems problematic. It just seems undemocratic to not to have those people which really don’t own those shares. It’s their investors not have them involved in the process at all. And I think that was one of the biggest legit worries about the rise of passive was the concentration of power in those two firms. But this is, I think one step to deal with that. I think there’s a bill in Congress about that. Senator Dan Sullivan of Alaska proposed that portfolio managers or portfolio management companies are not allowed, should not be allowed to vote proxies of index funds.

0:49:52.9 : Yeah, this is another thing that was brought up by the guy from Janice for the op-ed in the Wall Street Journal saying just they shouldn’t be allowed to vote. Part of me understands this. But I talked to my ESG friends and they think that passive at least take summit ESG into account. Whereas active just wants profits. They’re a little more cutthroat. Don’t care. And they may actually encourage pollution because they want more profits and they don’t want to those extra costs. I think the combo is healthy. Passive has a little more, much more long term viewpoint. They’re never going to sell the stock. They can. Active can sell tomorrow. So I think maybe both actually, you might get the best of both worlds. So I’m of that camp. But I can understand why they would put this bill in. But that you know, if you’re ESG, I think you would not like this bill. Am I wrong, Ellen? We’re just it’s only active managers.

0:50:49.6 : Well, I actually I think it’s really worth distinguishing between fund managers and asset owners. Right. Pension funds, endowments, etc. I this is controversial, but like I would much rather that pension funds vote than fund managers. Because fund managers are trying to get more business all the time. So they don’t want to piss off the sorry, I don’t know if you have language restrictions. OK, great. They don’t want to piss off the pension fund of a company they’re trying to get the business of. Right. So like Exxon’s got a pension fund associated with it. Right. All of its employees will pay into that that pension fund. BlackRock wants that business. So there you know, there’s a limit to how much they’re going to want to be bold, even when they’re real

Visit Podcast Website

Visit Podcast Website RSS Podcast Feed

RSS Podcast Feed Subscribe

Subscribe

Add to MyCast

Add to MyCast