The Creative Penn Podcast For Writers

Writing And Producing A Micro-Budget Film With Jeffrey Crane Graham

How can you pick yourself, rather than wait for someone else to pick you? How can you take control of your independent career and bring your creative vision to life? Jeffrey Crane Graham talks about his experience as an indie filmmaker, with lots of tips for indie authors.

In the intro, 6 Types of Submission Comments BookBub Editors Love to See [BookBub]; Author platform is not a requirement to sell your novel or children’s book [Jane Friedman]; Your Author Business Plan and/or Business for Authors 50% off with discount coupon PLAN on CreativePennBooks.com; Spear of Destiny; Ruby Roe rainbow foil hardcover Kickstarter; Updated Author Blueprint coming soon; I'm interviewed on writing memoir [QWERTY Podcast].

Today's show is sponsored by Draft2Digital, self-publishing with support, where you can get free formatting, free distribution to multiple stores, and a host of other benefits. Just go to www.draft2digital to get started.

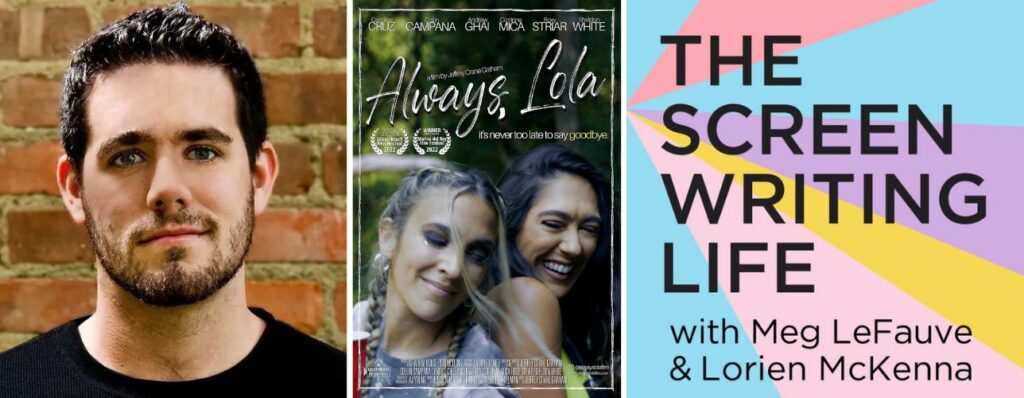

Jeffrey Crane Graham is a writer, director, and podcast producer. He wrote and directed the multi-award-winning film Always, Lola, and has also written comedy shorts. He produces and co-hosts The Screenwriting Life podcast.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Choosing yourself, rather than waiting for someone to pick you

- The process of creating a micro-budget feature

- Writing screenplays that are “practically shootable”

- Tips for authors who want to get their books on screen

- Marketing a film in a crowded market

- How the film festival circuit works for indie filmmakers

- Possible uses of AI in the filmmaking process that are not the act of creation

You can find Jeffrey at JeffGrahamDigital.com. You can find Always Lola at AlwaysLolaFilm.com.

Transcript of Interview with Jeffrey Crane Graham

Joanna: Jeffrey Crane Graham is a writer, director, and podcast producer. He wrote and directed the multi-award-winning film Always, Lola, and has also written comedy shorts. He produces and co-hosts The Screenwriting Life podcast. So welcome to the show, Jeff.

Jeffrey: Thanks, Jo. I'm honored to be on the show. As I told you before we went on air, I'm a fan of your podcast. So I am glad to be here.

Joanna: Oh, good. Well, lots to talk about. First up—

Tell us a bit more about you and how you got into screenwriting and film.

Jeffrey: So I'm from Cleveland, Ohio. I feel like I got especially interested in writing in middle school, I was writing a lot of short stories. Then I feel like in high school, I got the ambitious idea of like, “I'm going to try to write a novel.” That's something I would still like to do before I die.

I always think of novelists as like real writers, and screenwriters are aspirational novelists. Just because the idea of a novel, I think, is so intimidating.

The idea to first kind of start writing for film and TV—I think most screenwriters can point to a movie that feels pretty definitional for them—I think for me, that would have been Little Miss Sunshine. It was the first movie I watched where I really subconsciously thought, somebody wrote this.

I feel like film culture, especially feature films, are so built around the idea of directors being the author of the movie. Whereas I'm always most interested in who penned the script.

Little Miss Sunshine, I remember watching it and specifically loving the dialogue and the twists with the characters that you learned throughout the journey. I distinctly had the realization that somebody literally wrote words on a page that these actors are saying, and I have to know who that writer is.

Of course, that writer is Michael Arndt, who in such a cool full circle way I got to interview on the show I co-host, The Screenwriting Life. I did my best to maintain professionalism as I told him he was one of my heroes.

Then from there, I just started writing more and more scripts. I ended up optioning a half hour pilot, which kind of got me excited to move to Los Angeles. And here I am now talking about my debut feature film, which is called Always, Lola.

Joanna: A few things I want to follow up on there. First of all, it's so interesting, you talk there about when you notice the writer. I was just thinking about the TV show Succession, which I love.

Jeffrey: It's one of the best of all time.

Joanna: Yes, and the dialogue is so good. It's so cutting. It's the most violent family dialogue, but not in a violent way. You know what I mean?

Jeffrey: Of course, yes.

Joanna: It's one of those shows where I'm, like, wow, these writers are really good. Then the other example I was thinking of recently, we were watching season two of Reacher the TV show. Season one—I don't even know if this is true—but we were like season one had great writing, season two had terrible writing.

Jeffrey: Interesting. It happens.

Joanna: It's interesting because often we don't think about the screenwriter, or the screenwriting team. When you were saying that, it's really the first time I've thought about—

When do you really notice the writer, as opposed to the director?

Jeffrey: Well, it is interesting. I'll talk about Succession. I don't know as much about Reacher. It's funny because television is also an interesting one, and I'll get to this, but it's so collaborative that sometimes you're not sure if it's the studio, or the directors, or the showrunner, or someone in that room. That's true of movies as well.

I think with Succession especially, Jesse Armstrong had had such a long career as a comedy writer. I don't know if you're a Peep Show fan…

Joanna: No.

Jeffrey: Great, great show. He co-created that with a writer I admire named Sam Bain.

Since he had worked so long, specifically in more comedy zones, I think Succession was such an interesting synthesis of it's a hilarious show, like you mentioned, and the dialogue is so cutting and brutal. It's also this Shakespearean look at the intensity of family, and legacy, and living up to the impossible standards that your parents set for you.

Interestingly, Jesse Armstrong hired a ton of playwrights for that show. So a lot of the writers room came from acclaimed, under-seen, like West End plays. So because I think playwriting is so dialogue-heavy and Jesse Armstrong has talked about the influence of Shakespeare on his work, maybe that's why the writing especially stands out.

I also think, interestingly, I think when you look at playwriting —

The playwright is usually considered the author of the work. Whereas in screenwriting, sometimes the director is considered the author of the work.

I've always kind of objected to that.

Joanna: Yes, that is interesting. So from the big TV shows and the big films, and you describe Always, Lola as a micro-budget feature. So just explain a bit more about that. Like, did you do absolutely everything?

Tell us about the process of getting that done.

Jeffrey: I did a lot of it, I will say. I want to be careful to make sure I'm giving credit to all the departments who helped on the film.

It is interesting with your first feature, so much of it is just kind of pulling the cart yourself and getting it over the finish line.

Budgetarily, and I'm happy to talk about this, it's a big part of your show. I would say like 80% of the budget, which for production was somewhere between $20,000 – $30,000, was my own savings, with probably 20% of that coming from producers.

Then once we got into post production there were some additional costs that come up from editing and color correction and sound. So financially, a lot of it is my own investment.

I mean, obviously, I wrote the script. I was a huge part of getting the movie cast. I did write for a number of actors that I already knew who were sort of in development with me before we even decided to put it up on its feet.

For some of the characters, I cast them in a very traditional way. I did it by reaching out to agencies through my production company email that I founded to put the movie together, and I cast that in a traditional way.

I think it's really important to credit my director of photography, a brilliant DP named AJ Young. I think this was his 11th feature. I think like the look and the way the movie is lit, I worked very closely in tandem with him. He has a ton of experience on big budget movies all the way down to these sort of scrappy micro-budget films.

So he really understood how to work with the budget we have to make it look as good as it could. So I will credit him, but in terms of the other departments and post production, most of it was just me.

Joanna: Yes, and that's why I guess we're talking, really, is that you're an indie filmmaker. You've done it on this $20,000 to $30,000, which was your savings, and obviously a lot of your time, and your relationships, and all these things you put into it. So this is a labor of love.

Tell us about the idea behind the film.

Like what possessed you to do this?

Jeffrey: Yes, totally. I'll talk from a personal perspective first and then practical perspective second. The story is kind of a feel-good coming-of-age dramedy. A lot of critics have mentioned the movie The Big Chill, which was a big inspiration for me as I was writing.

I love Lawrence Kasdan, and in general, I sort of love 80s hangout ensemble dramedies. Like The Big Chill, or The Breakfast Club, or pretty much anything that John Hughes was doing in the 80s. I think it's harder and harder to find character-driven dramedies. They were so popular, and they've kind of gone away.

So I bring that up because the movie is loosely inspired by the death of my best friend from high school. The movie follows these five best friends who are reuniting on their annual camping trip to mourn the loss of their friend who used to throw that trip. But on this trip, obviously she's not here because she died the year before.

As they kind of talk and discover secrets around her death during the trip, it threatens to not only destroy their friend group, but their memory of her and their understanding of their own mortality. I think it is a really important coming of age moment.

I always say that losing a parent or a grandparent is a very specific kind of grief, but losing a peer, especially as a teenager, is a very different kind of grief. I think most people can point to that first moment they lost someone who was their age. So that's really kind of what the movie is about.

From a practical perspective, it's funny —

I'd written this draft with the intention of really writing and putting together a low-budget, practically shootable film.

It was with the idea of either giving it to a producer or sort of pitching it out as something that could be made on a really low budget.

This was all kind of happening as the pandemic was really reaching its peak. Obviously, the pandemic was horrible, but if we wanted to look at one silver lining, I do think it forced a lot of us, especially creatives, to assess why they were really living their life, you know, as things were slowing down for them.

My wife actually looked at me, and she was like, okay, as things have slowed down and we're sort of taking a 30,000-foot view of our own life, we have two options here. One of them is to grow old in a nursing home and be 95 and still talking about the movie we never made. The other option is to just try to figure it out ourselves and see what happens.

Both of those sound really, really hard, but I actually think the regretful one sounds much harder. So we have to make the other hard choice. That was the moment when we decided to kind of go all in.

Joanna: So first of all, I love this phrase, “practically shootable,” because I have written a few screenplays and adapted some of my own work. I did one for a pilot with my Mapwalkers as kind of a feature, and I pitched it to an agent and they said, “Oh, this is like $100 million.”

I was like, okay. He asked if I can write something cheaper and, I guess, more effective.

What does “practically shootable” mean if people want to write screenplays or books that might get adapted?

Jeffrey: That's a great question, and I kind of have a two-pronged answer for this, if that's okay. It's funny, a lot of studio-working screenwriters would say that when you approach the page as someone who wants to get into the system and maybe be selling your work or getting staffed on a TV show, you shouldn't be thinking about budget as you approach the page.

Instead, you should just be writing the sample that feels like most true to your voice and version of you as a writer that you can.

But I think there's also another prong that's kind of increasingly important to think about. That is if you plan on producing your own work, especially early in your career, and I think it used to be, sort of like in the old days of Hollywood, that you could build your career on just a sample, and it would get bought and sold, and then you'd be in the system.

More and more, especially for feature film writers, especially writer-directors, their debut is more self-produced.

You know, the 90s, I look at filmmakers like Robert Rodriguez and Kevin Smith, and even recently, Lena Dunham, her early work was self-produced on a micro-budget.

There's a filmmaker I like a lot named Cooper Raiff who just won a big award at Sundance a couple years ago. His first feature was self-produced for like 16 grand.

There's a really exciting filmmaker named Emma Seligman. She had a movie come out this year called Bottoms that I think is like one of the best of the year from last year. Her debut feature film, Shiva Baby, is also kind of a masterpiece, and that was self-produced.

So I bring all of that up because it's more and more of a viable way to launch your career as an indie filmmaker to start, which then gets you those meetings and gets you into the system to pitch your more expensive movie.

So when you're thinking about a practically shootable film, you do want to be thinking about budget, and you want to be thinking about what you can actually do to get your film up on its feet and kind of not shoot outside of your means.

So things like limiting your locations. You know, locations are by far one of the most expensive elements of a feature film. It's called a company move when you ask your entire production, cast, crew, wardrobe, craft, food, to move to a new location. Obviously on a production, time is money. So the less you can be moving around, the better.

So I encourage feature filmmakers, especially micro-budget feature filmmakers, to think about these sort of 50k or less movies as their own kind of genre and look at them as a case study.

What are the commonalities? Usually it's a small cast, limited location, not a ton of set pieces, maybe a juicy character-driven theme.

If you're interested in this, I actually do teach a five-part course on what it means to write, produce, edit, and distribute a micro-budget film. I've become obsessive about this. So I'll include the link to that class in the description below if you're interested in taking it.

Joanna: Oh, great. We can add that in at the end.

What's funny is after I did pitch this expensive thing, I did end up writing a horror micro-budget. So I wrote a novella, it's called Catacomb, and I also wrote the screenplay alongside it. I made a pitch pack and all of this, and then I haven't done anything at all with it.

I guess I'm scared. I have booked a place at the PitchFest in a couple of months, but I am a little scared about doing it.

What are your thoughts for authors who want to get their books on screen but don't necessarily want to adapt them themselves?

Jeffrey: I totally understand that screenwriting is a totally different medium and craft than novel writing. Similarly, like the idea of adapting my debut feature into a novel is uninteresting to me, to be totally honest. So I understand that.

First of all, I think you're smart to be looking at horror as a practical way to put a micro-budget film up on its feet. They're usually the most lucrative when it comes to these low budgets. Of course, the two most famous versions of micro-budget feature films are The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity.

So I think what I would do is look for other super low budget films that might feel similar in tone or look or story to yours and look at who's producing on those. You've got to think, those producers are also at the beginning of their career, and they want to keep their train on the track as well.

So looking at those names, going to IMDb, or IMDb Pro especially, and see if you can find a contact or way to reach out. Then just sending a little email over and saying, “I love your work.” First of all, flattery is one of the most important ways to make a good connection with someone.

Be honest about what you loved about their material, and let them know, “Hey, I'm a novelist. I have this IP. It's well reviewed, and I think it could make a great feature. Would you ever want to get a coffee and just talk about it?”

I would say 99% of the time, these upcoming producers will at least take the meeting because you've got to remember, their job is to get work made and they want to keep their name on projects. So it's a mutually beneficial relationship.

I think it's so easy to think about producers as the bad guys or like the scary sort of dark arts element of film production, but they are creatives too. Remember, they got into this business because they're in love with storytelling in a different way. So reach out, you never know what will happen.

Joanna: It's interesting you say that because there's also a lot of—I say horror again—but horror stories amongst the author community. There's a book called Hollywood Vs. The Author, where there are stories of authors who've done this. You know, they've sent things in, and then films have been made. There are court cases, and you must be careful of contracts because you might get ripped off.

I feel like on the one hand, there's a lot of hope, which means there are a lot of rip off things.

Then there's also a lot of fear around what could happen in a bad way. Or even, I guess people look at films that are made of books that they love, and they say, “Oh, it was terrible. It ruined everything.”

Where's the balance between Hollywood being full of sharks and the hope of making something?

Jeffrey: It's hard. I don't want to sound like a pessimist on the show, but I think it is an interesting moment in terms of TV and film because the industry at large is not quite as lucrative as it used to be.

Everyone, from indie filmmakers to big studios, are trying to figure out how they can continue to keep the business as financially viable as they can.

Streaming has been good in a lot of ways, and it's created a lot of jobs for people, but the big lesson over the last 10 years is that it's not profitable.

So something needs to change.

I think I say all that because I think like the big $500,000 spec script sale for a first-time writer, it's not really happening anymore. So I think like there is an element of adjusting your expectations and knowing that for your first film, especially, you might not be doing it as much for the big paycheck.

It's more for the chance to really launch your career, get your work and your voice up on screen, and use that as a chance to start doing bigger and bigger things. There are some red flags, however, that I would really look out for.

One of them is if a producer is asking you to pay them to take your work out. That's a no, no, no. A producer is invested and on your team. So both of you are looking to benefit and profit from the idea of your work.

That should be the producer is expecting to make money later down the road. When the movie gets sold, there will be a writer deal and a producer deal, and both of you will benefit from that. The producer should not benefit until someone is paying both of you, if that makes sense. So that's a big red flag.

Also, keep the rights.

If a producer is asking him for like 5% of the rights of the material or whatever, that's also a no go. Whatever it takes, hold onto those rights.

Other than that, I think $1 option agreement, where a producer will pay you $1 to get the right to go shop it around. That's not super uncommon.

If you're an unknown, I'd say just be limited about the number of time on that option. Maybe it's six months, maybe it's a year, whatever, but that's not necessarily fishy when it comes to early in your career.

Joanna: Yes, it's interesting. You mentioned that things are not as they used to be. It's the same in traditional publishing. The market is very crowded for all of us as creatives. So given that you're an indie filmmaker—

How are you reaching film lovers in such a crowded market? What have you done in terms of marketing?

Jeffrey: You know, of course, podcasts! I'm grateful to be here with you now.

I do hope in your audience that there are some interested aspiring filmmakers. I think you'll like the movie, but it's also worth checking out as a case study to see what you can do for $30,000. As I mentioned, I think it's important to be studying this if you want to do it yourself.

This is a question that indie filmmakers are asking, but this is also a question that big studios are asking.

Michael Mann released a movie this year called Ferrari. Of course, he's one of the highest grossing directors of all time, and the movie is just not doing well. It's interesting, because it's the kind of movie that would be like guaranteed gangbusters in the 90s.

So I think we're all competing for attention. I think a lot of people are using their free time and their leisure time to be on social media.

So I think the best way to get people interested in your work is to try to make organic human connections and build a community of your own.

I'm sure, Jo, a ton of your listeners are also invested in your work. I'm lucky I have the same thing. The podcast I do has a decent following, and a lot of those folks have checked out the movie.

Festivals were super helpful. You're meeting filmmakers there. Winning awards at those festivals was nice because that gave us some leverage to promote. I think trying to make niche connections and find communities to promote your work is going to be a helpful way to get it out there.

Joanna: So you mentioned there, winning awards at festivals, like it's just something that you just add to a checklist. So did you aim for that?

Did you do things specifically for specific awards? Then did you just enter them?

Or like what is the festival thing for film?

Jeffrey: The festival circuit. Well, I guess to rewind a little bit, this whole thing has been such a process of discovery. Going into the movie, we didn't have any intentions of necessarily selling it.

I think Laura and I decided, we were willing to take a financial risk just on the opportunity to get this work up on its feet and give me the chance to direct in the same way that film school would do for probably far more money.

So really from the start, we thought like worst case scenario this will be 30k as a chance to get on set, get experience directing and have a feature film. Whether or not it sells, at least I'll have a screener link that I can send it producers.

So everything else, the festival circuit, and the awards, and the sale, and the deal have all been gravy. In terms of festivals, I certainly was not aiming for any kind of award. All the awards that we've won have been like a really pleasant surprise.

Festivals are an interesting one because there's kind of three tiers of film festivals. There's the top tier, which are also markets, where films will actually get sold at those festivals.

So I know you're international, but for Americans, it would be like Sundance, obviously, the Tribeca Film Festival, the Toronto International Film Festival and Telluride, maybe South by Southwest.

Those are kind of the only five sort of North American festivals where deals will actually be made. I think in Europe, it would be like Cannes, obviously, and then maybe Berlin and Venice. Besides those three, you're not going to see a lot of film festivals where sales are actually happening at those festivals.

So then there's another tier of festivals that are more like second tier film festivals. Those are really valuable for my type of movie where you don't have any big names. You might be able to find independent agents there or other sort of low-level distributors that you can at least get meetings with.

Those are great way to meet people and generate some momentum and heat and press around your movie to kind of create a different sort of market than you would be at those top tier film festivals.

The general strategy is to apply to those top tier film festivals first. That's kind of your lottery ticket, it's unlikely, but you never know. The reason why you want to apply to those first and wait it out is because once you've debuted at a film festival, the likelihood of getting into another film festival becomes far less.

You know, because Sundance wants to be the festival to premiere your film. So you want to reserve your premiere status for the festival that you really want to premiere at. So you want to aim for those top tier festivals first.

Joanna: And the relationship building—

Were you going along to these festivals for years beforehand, seeing how it's all done?

I feel like it's quite similar to book awards or conventions. You need to know how things are done, you can't just enter stuff into random things.

Jeffrey: You know, I think somewhat regretfully, I wasn't really going to film festivals before this feature. I think had I been, I would have had a little bit more knowledge as to how to play the game.

I set a lot of meetings with filmmakers who had done this already in a very similar model and just grabbed coffee with them to sort of learn what advice they would give me.

I think it's all about knowing your movie. This is I'm sure true for independent novelists as well, but it's like, know what you've made, know your voice, and know your market.

Then look for film festivals that are catering to a similar sort of vibe and work within those parameters. Write a cover letter as you're planning these festivals and give the festival programmers a reason to program you.

You know, if they're getting 200,000 submissions, why would it be advantageous for them to program you, specifically?

Maybe you're local and you know people that would come to the movie, maybe you look at other movies they programmed in the past and how your movie would slate well into their programs. So do the work for them and make it easier for them to program your film.

Joanna: I guess a lot of us in the indie author community, we use more algorithmic marketing around keywords and metadata, and we do paid ads and all of this. So did you consider any of that at all? Or—

Has it all been sort of human-based marketing?

Jeffrey: I mean, on my end, it's mostly been like the human-to-human connection. I will say, even though we're an independent film, we did sell to a distributor.

They have a marketing budget that they need to recoup before we start earning on the film, besides the upfront payment that we got for selling the movie to them.

So they have X amount of dollars that they've spent on marketing. I don't exactly know where that money went. I have a meeting with them when we get our first quarterly and they're going to talk through how they marketed the movie. I do think they may have done a targeted ad campaign on Facebook when we first were released on VOD.

I'd say most of the engagement and viewing we've gotten have been through word of mouth. We did get a great Rotten Tomatoes score when we first debuted which I think it's been very helpful. There are a number of people who just look for positively reviewed indie films and use that as a chance to check out a movie.

I think we were released at a good time. We got kind of lucky because we released like right after both strikes resolved, so there was an opening for us. We weren't competing with a ton of big studio movies when we first released.

Again, I don't know. I mean, like it'll be interesting to see when we get our first quarterly how we're actually doing. So talk to me in two months, and I'll either be thrilled or beating my head against the wall.

Joanna: Yes, it's interesting. So you mentioned the strikes there. Of course, the Writers Guild of America went on strike, and then also the Actors Guild went on strike. As part of that, that was obviously in negotiations for lots and lots of things, but part of that was AI.

So we're recording this at the beginning of 2024, and the text-to-video stuff is really starting to take off.

What are your thoughts on the use of AI in filmmaking?

Whether it's screenwriting or any of the other things? What are your thoughts on using it as a creator, without going into the strike stuff?

Jeffrey: Sure. I think I would be similar to where the guild stands. There's a writer I like a lot named John August who has a great screenwriting podcast, and he talks about AI a lot.

I don't think we should just like flat out say AI is not a useful tool for creatives. I know a lot of showrunners who will type something dumb in AI just to get the room talking, or generate brainstorming ideas, to then let creative people actually fuel their own work and write their material.

I think what gets very dangerous is when we're asking machines to be writing drafts of something. I think as a brainstorming tool or a research tool, it's very valuable. I think when we start asking robots to start making art, I get a little scared.

It's funny, I was talking to my brother-in-law about this, and he was like, “Why are we afraid of this? Like technology has been great for creatives. Look at the printing press. Everyone was so afraid when that came out, and it's only been great.”

But the difference to me is that the printing press was a tool that helps work/art created by people get into the hands of more people. Something like the internet has been great to reach people and send your work out.

This is the first time in human history that we're asking the question, should robots be the ones making the art rather than replicating or distributing the art? I feel very strongly that once we give over the sort of beautiful beacon of making and creativity over to machines, we're in deep trouble.

Joanna: I say it's a continuum.

If you have 1% to 100% computer-generated, everyone's going to sit somewhere on that curve.

We all use lots of things online, in general, a lot of which is now powered by AI.

There's a big difference between click a button and output a screenplay, to using it for like I just did earlier. “Here's a picture of a door. Give me 10 ideas for what might happen when a theology professor steps through this door. Just give me some ideas around this for the story.”

Now, some of that was completely crazy, and some of it was interesting enough to spark other ideas for me. So I think there's a creative spark in our creative process, in a human creative process, versus the mass output, which is not something either of us are advocating. [For my approach, see The AI-Assisted Artisan Author.]

Jeffrey: I totally agree. I think the other important thing is a lot of people will say like, “Well, you know, people won't just settle for AI-generated art,” but I would slightly push back on that. I think they would, unfortunately. I think people's tastes adapt to the work that's being produced and made for them.

Without being specific, I do think there are movies and TV shows that, in essence, could be AI-generated that people really like because that's sort of the cultural bar that people are setting for an audience. I do think it's the job of creatives and producers to be the tastemakers that sort of fuel cultural conversation.

So I would like to be optimistic enough that people won't settle for crap if AI is making it, but unfortunately, I'm not optimistic enough to believe that. I think if you look at people's taste, it already has been lowered by the tastemakers of popular art today. So I don't want to get too pretentious about this, but I do think people will settle for what's made for them, and it's our job to try to make good things.

Joanna: Yes, although I would also say I think there's room for different things. So for example, in the AI audiobook narration space. I listen to a lot of audio, and I listen to it on like 1.5x – 1.7x. I listen to a lot of mostly nonfiction. Every human narrator sounds like a robot at 1.7 speed! It really doesn't matter, I just want the information.

AI narration means that people can have audiobooks, audio content, in every language, every dialect, that we just can't have otherwise.

I guess the other interesting thing would be McDonald's versus a nice restaurant that you go to, and sometimes you need a McDonald's, right?

Jeffrey: That's true. That's true. I would just love to believe, though, that like McDonald's food, there is still an element of human thought behind it. There are executives at McDonald's who are still invested in making something delicious with a human brain behind it.

I do agree. I mean, like, I love my guilty pleasure TV just as much as I love Succession.

Joanna: Yes, exactly. So it is interesting.

So that's the screenwriting, but as a filmmaker, if you're looking at your career decades ahead, I mean, it's got to be like 100% likely you're going to be using some kind of AI in your production. Whether it's special effects, or whether it's bit part actors, or music, or I don't know.

How do you think other parts of AI could be used in the filmmaking process?

Jeffrey: It's interesting. I will say the type of work I write and am interested in tends to be kind of very low concept, human driven stuff, at least right now. So it's not like the material I write or my voice as a writer pushes towards like big, special effects type of set pieces.

I think you're right. It's hard because we're taking, especially the guild's, are taking all of this information and data like step by step. So it's hard for me to answer that, but I want to be someone who is curious and open minded about it. I do think like the shutdown-the-conversation mentality is a little naive.

Joanna: Yes, I mean, obviously those strikes are now over, and they got a contract through. It allows the use of AI tools, but not to credit AI as a writer. So as in, they can use it in the ways that we've talked about around ideas.

I'll tell you what I did use it for. I've tried Final Draft, and I find it really not intuitive as someone who doesn't write in screenplays first. So I was writing out, kind of turning each scene into just plain texts, and then I would put it into ChatGPT and say, “Can you reformat this for screenplay format?“

Jeffrey: Oh, that's fascinating. I'd love to try that.

Joanna: Then I would put that into Final Draft. So it just helped me with a bit of that. It's like a technical thing that I don't want to spend the time learning Final Draft. You know what I mean?

Jeffrey: As a tool, I understand it. It's like, at a certain point, if you're doing your own research versus an aggregator doing that research for you, what is the big difference? I think it's just being thoughtful about how it's being executed.

Again, the fundamental question in my opinion—

Is this a moment when art or creativity is being handed to a machine?

Like is what I consider the sacred act of creation, is that being handed over to a robot?

It's so interesting to me, because I will say, Hollywood has a long history of telling stories about giving too much power to machines, and I can't think of a single one where the climax of the movie is, “I'm so glad we all let the robots win here.”

Joanna: Well, I've got one for you, The Creator. Have you seen it yet?

Jeffrey: No, no. I've heard it's an interesting one, but I have not seen it yet.

Joanna: It is excellent. It was so funny, because I was watching it, and it feels almost like a big budget American movie. Then at one point, I turned to my husband, and I was like, “I don't think this is American, because of…” Well, I'm not going to spoil it for you, but I was watching it, and I was like, goodness me, this is not an American movie.

It is not. The producer, screenwriter, director, whatever he is, is British. So that was really interesting for me, because you mentioned there, like obviously the Hollywood big budget movies. Terminator, blah, blah, blah, but they're all pretty much American. Whereas I think there are different views by different people.

The Creator is an excellent, excellent film. It's like one of the best films that I've seen in ages, because it's so nuanced and interesting around what the future of AI and robotics could be. So I'm just going to encourage you and other people to watch that.

Jeffrey: Okay, I'll add it to my list right now. Maybe I'll watch it tonight.

Joanna: Yes, although we said there's so much to watch in the world. It's definitely, in terms of the AI thing, it offers an alternative view.

So we're almost out of time, but I did want to cast your mind forward. This is your debut micro-budget feature.

What are your plans? How does a career progress from there?

Jeffrey: It's been really helpful for me to have made and sold a film. Obviously, like the big picture thing is that when I set meetings with producers or I'm talking to management, I have a tangible product that shows that I understand the mechanics of feature filmmaking in a way that, you know, the evidence can't lie.

I did it, and I sold it, and it's on Apple, and you can watch it now. There is an element of grit that comes with having done that that gives you a level of credibility when it comes to the next movie, and building your career, and being taken seriously as someone in the business.

Of course, there's also the small stuff too. Like, when we sold the movie, we got a hit in Deadline, which is a major publication that talks about Hollywood news.

Then I had a couple folks reach out to me that were like, “Hey, I saw you in Deadline this week.” So it's just like a tangible level up that has opened a lot of doors for me as I'm continuing to kind of set meetings and really pitch on the next one.

So it's, again, I think in like the 90s, it would be selling your feature script as like the calling card for who you are as a writer. I do feel increasingly, now, it is self-producing your debut feature that serves as your calling card.

So I think just the credibility that comes with having done it, and now that it's up on platforms and has been written about in the trades, it's at least evidence that I'm not too much of a fraud, if that makes sense.

Joanna: Is your goal to work with bigger and bigger budgets, bigger and bigger casts?

Or do you want to stay making these smaller, more people-focused movies that you mentioned?

Jeffrey: You know, it's funny. I have two things I'm kind of working on right now.

One of them is like a bigger budget, maybe like $20 to $30 million dollar kind of big dumb cruise ship comedy. The other one I'm working on is like similarly a small character and coming of age movie that I think could be made for far less.

So I think it's smart for filmmakers to have multiple projects in their cooker that sort of serve different lanes or markets. I think most importantly, still really stay true to the voice and sort of essence of who that writer is.

It's important as you're taking meetings to be able to tell a cogent story about who you are as a writer and what kind of stuff you write, so that producers can understand how you would slot as they go to their bosses and pitch the idea of whatever you're making.

Especially in Hollywood —

I think so much of finding your lane as a writer is about telling the story of who you are as a writer. That almost feels as important as your work.

If I'm thinking about someone whose career I really admire, I love Nicole Holofcener. She just came out with a movie this year with Julia Louis-Dreyfus called You Hurt My Feelings. I love The Land of Steady Habits.

She's someone who writes and directs a lot of her own independent features that are really small, but she also writes on big studio movies to kind of come in and rewrite, or even if she's not directing, she is also in the studio system. So I think she has a really interesting career. I would love to think that maybe I could get there one day too.

Joanna: Fantastic.

Tell us where people can find you, and also your film course that you mentioned, and of course, Always, Lola.

Jeffrey: Totally, yes. Thanks so much. To connect with me, the best place is probably just to head to Instagram. You can find me there at Jeffrey Crane Graham. Totally DM me there if you want to connect. I am happy to answer questions, and I love connecting with other micro-budget filmmakers. So if you have questions, totally come reach out to me there.

Then you can go to my website, which is JeffGrahamDigital.com. There's contact information there as well.

That's also where you'll find my film course. It's a five-part class all about micro-budget filmmaking, from writing all the way through sales, distribution, and finding an agent. I even have neutralized agreements and contracts that will serve as a great springboard for you as you jump into pre-production. So that's on my website.

Joanna: Fantastic. Well, thanks so much for your time, Jeff. That was great.

Jeffrey: Oh, this was so much fun. I mentioned it, but I'm a big fan of your show, so I'm honored to be a part of it.

The post Writing And Producing A Micro-Budget Film With Jeffrey Crane Graham first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Visit Podcast Website

Visit Podcast Website RSS Podcast Feed

RSS Podcast Feed Subscribe

Subscribe

Add to MyCast

Add to MyCast