A Mouthful of Air: Poetry with Mark McGuinness

The Oxen by Thomas Hardy

Episode 16

The Oxen by Thomas Hardy

Mark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘The Oxen’ by Thomas Hardy.

https://content.blubrry.com/amouthfulofair/16_The_Oxen_by_Thomas_Hardy.mp3

Poet

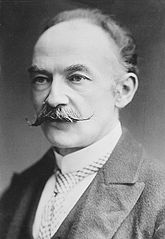

Thomas Hardy

Reading and commentary by

Mark McGuinness

The Oxen

by Thomas Hardy

Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock.

‘Now they are all on their knees,’

An elder said as we sat in a flock

By the embers in hearthside ease.

We pictured the meek mild creatures where

They dwelt in their strawy pen,

Nor did it occur to one of us there

To doubt they were kneeling then.

So fair a fancy few would weave

In these years! Yet, I feel,

If someone said on Christmas Eve,

‘Come; see the oxen kneel

‘In the lonely barton by yonder coomb

Our childhood used to know,’

I should go with him in the gloom,

Hoping it might be so.

1915

Podcast transcript

As we are approaching Christmas this week, I thought we could do with a Christmas poem, and this was the obvious one that came to mind.

To me this poem is a bit like the movie, It’s a Wonderful Life, it’s synonymous with Christmas, and it’s one of those things that it feels like it wouldn’t be Christmas if I didn’t have another look at it. And part of me thinks, ‘Oh no, not that again’, but actually, each time I do give it another spin, I’m glad I did. It feels like it’s really Christmas, and I enjoy it every time.

So like It’s a Wonderful Life, ‘The Oxen’ is a cosy and charming and well-beloved Christmas piece. It was first published in The Times newspaper in December 1915, since when, it has been anthologised and reprinted and read at endless carol services and on festive TV and radio shows. It’s been set to music by over a dozen composers, including Ralph Vaughan Williams and Benjamin Britten. So it’s almost too popular for its own good. It’s become a Christmas cliché.

But another thing it has in common with It’s a Wonderful Life, is that yes, it’s cosy and charming, it’s a feel-good piece. But if you look carefully, then both the movie and the poem have some pretty dark shadows. So what I want to do today is look at the light and the dark of this poem.

And eagle-eyed, or should that be eagle-eared listeners will have noticed that this means that Thomas Hardy is the first returning poet on A Mouthful of Air. Back in Episode 8 I read his poem ‘Beyond the Last Lamp’, so no prizes for guessing he is a favourite poet of mine, and I’m happy to welcome back.

So the poem hinges on a legend from the West Country, the south west of England. According to this legend, at midnight on Christmas Eve, in other words, on the first stroke of Christmas Day, the cattle in sheds and barns and farm yards, I guess out in the fields, if any of them were out there, would kneel to welcome the birth of Jesus Christ the Saviour and show reverence to him, just as they do in the cribs that we see at this time of year: you’ve got Jesus in the centre and Mary and Joseph bending over the crib, and before the shepherds get there, before the three wise men get there, you’ve got the you’ve got the animals: you’ve got a donkey and what I always used to think was a cow, when I was small, but it’s really an ox. And they’re not mentioned in the Gospels, but those two animals have been part of the crib since way back when.

And at the beginning of the poem, the speaker is looking back at a memory of being told the legend years ago by an elder, when nobody thought to doubt that it was true. And then in the second half of the poem, he moves on to the present. And we get the sense that he is now much older, more experienced, and if not necessarily wiser, then at least more sceptical about legends such as this. And yet, he says that even now, if somebody invited him to ‘come; see the oxen kneel’ at midnight on Christmas Eve, he would go along with them, ‘hoping it might be so’, hoping that the legend was true.

Now, back in Episode 8, I shared with you that one reason I love Thomas Hardy’s poetry is that we both grew up in the West Country, which he fictionalised in his novels and poetry as Wessex, the name of the old Anglo Saxon Kingdom, where King Alfred used to rule once upon a time.

Now, growing up in the West Country, I don’t remember anybody telling me about cattle kneeling on Christmas Eve at midnight, nor inviting me to a lonely farmhouse in the middle of the night to check it and see if it was true. But I do remember meeting quite a lot of old people in particular, who spoke pretty much the way the elder speaks in this poem. And I recognise a couple of the dialect words.

So we’ve got ‘barton’, or ‘barrton’, as we say in Devon, which originally meant ‘farm’, but later on came to mean ‘farmhouse’. It comes originally from two Anglo Saxon words: ‘bere’, meaning ‘barley’ and ‘tun’ meaning ‘enclosure’. So a barley enclosure, a ‘barton’, was a farm, and I remember that word from place names in Devon, where I grew up.

And we also have ‘coomb’, which means a hollow or a valley, especially on the side of a hill or running up from the sea. It was in a word in Anglo Saxon, but it goes back even further than that, to Welsh and other British Celtic languages. And I remember seeing that in place names such as Ilfracombe and Combe Martin.

The poem’s form is also a very old and traditional one, that we have encountered before: it is ballad metre, which you may recall from Episode 6, when we looked at Edward Lear’s poem ‘The Jumblies’. And at least in its more traditional form, the main thing to look out for in ballad meter is the stresses, as the syllable count can be quite flexible. And it’s a 4:3 rhythm. So you have one line with four stresses, such as:

Christmas Eve and twelve of the clock,

You can hear the four stresses, on the syllables ‘Chris’, ‘Eve’, ‘twelve’, and ‘clock’. Then the next line has three stresses:

‘Now they are all on their knees,’

So you can hear those stresses on ‘now’, ‘all’, and ‘knees’. Listen for the 4:3, 4:3 rhythm in the first stanza:

Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock.

‘Now they are all on their knees,’

An elder said as we sat in a flock

By the embers in hearthside ease.

Got that? OK so this rhythm conjures up the world of Old England, almost like the tune of an old folk song or indeed a Christmas carol. And combined with some of the the old fashioned language, it means the atmosphere is pretty twee and sentimental and nostalgic.

So for example, you would get laughed out of a poetry workshop these days if you wrote in a Christmas poem and said ‘we sat in a flock / By the embers in hearthside ease’, it’s a bit too close to shepherds watching their flock by night. Not to mention stuff like ‘the meek mild creatures… in their strawy pen’.

And I guess we we can give Hardy a bit of leeway given that he was an eminent Victorian surviving into the 20th century by the time he wrote this. But in Hardy’s favour, I think it’s pretty obvious that he is aware that he’s being nostalgic and sentimental. You know he does say ‘So fair a fancy few would weave / In these years’.

And talking of ‘these years’, of course we can’t ignore the publication date: 1915. Because f you know anything about European history, then you know that this is one year into the First World War, a cataclysmic conflict, and one that Hardy responded to in several poems and letters where he expressed his sense of devastation. To him it was the most violent expression of the destructiveness of the modern world, which long before the war started had begun sweeping away the old traditions, the old faith, the old certainties.

Nine years later, he wrote a poem called ‘Christmas: 1924’, that included the lines:

After two thousand years of mass

We’ve got as far as poison-gas.

The mention of mass reminds us that by 1915, Hardy had long since lost his Christian faith, the faith of his childhood that is recalled by the legend of ‘The Oxen’. And that loss of faith was a shattering experience for him, and added to the melancholy tone of a lot of his writing.

So if we’re going to put Hardy in the dock for sentimentality in ‘The Oxen’, then the case for the defence would argue that he is setting up a deliberate contrast to the old world of his childhood, and by extension Old England, and the new world of doubt and despair and destruction. And maybe he’s overdoing it a bit, but isn’t that what poetry is for?

So on the one hand the atmosphere of ‘The Oxen’ is very similar to the innocent world of Under the Greenwood Tree, Hardy’s first published novel that came out that in 1872. That was a really charming story of carol singers and their families and a gentle love story that made use of a Christmas setting. But this poem, ‘The Oxen’, was written twenty years after Hardy’s final novel, Jude the Obscure, which still ranks as one of the bleakest and most depressing novels ever written.

And if we read ‘The Oxen’ in the context of the rest of Hary’s work, as well as the historical backdrop, the darkness is hinted at rather than spelled out, but it’s definitely there: in the date of publication, in the mention of ‘doubt’ in the first half, and the ‘gloom’ of the final stanza.

And if we look a bit more closely at the poem’s structure we can see he’s written it in two halves, each of which contains two stanzas, and they are beautifully balanced. So the first half, which begins on Christmas Eve years ago, with the elder telling the legend to the younger folk, ends with the word ‘doubt’ placed prominently in the last line of the second stanza:

Nor did it occur to one of us there

To doubt they were kneeling then.

Then the second half is another two stanzas of ballad metre, and it ends with the word ‘hoping’ at the start of the final line, which is exactly the same place where we found ‘doubt’ in the first half:

I should go with him in the gloom,

Hoping it might be so.

Now ‘hope’ was a very loaded word for Hardy. On the one hand it is it is of course hopeful, and it also appears at the end of another of Hardy’s most famous poems, ‘The Darkling Thrush’, which was written in at the turn of the century. The speaker of that poem, as so often with Hardy, is full of gloom himself, but he’s listening to the joyful song of a thrush. And he says the fact that the thrush is singing so joyfully in such a bleak world means maybe the thrush knows something he doesn’t:

So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

Going back even further than ‘The Darkling Thrush’, about twenty years earlier than ‘The Oxen’, Hardy had written a really dark poem called ‘In Tenebris’, which is Latin for ‘In darkness’, the first part of which concluded with these lines:

Black is night’s cope;

But death will not appal

One who, past doubtings all,

Waits in unhope.

Which is a much darker and more conclusive ending than ‘The Oxen’. In this poem the scales have really tipped – ‘past doubtings all’ – there’s no doubt left, and he describes someone waiting in ‘unhope’. So it’s not just the loss of hope, unhope is the opposite of hope, Hardy has created a new word to underline the obliteration of hope.

So I think it’s all the more remarkable that by the time we get to ‘The Oxen’, in the middle of the nightmare of World War One, we find Hardy balancing the scales almost perfectly – on the one hand we have doubt and darkness, but on the other we have faith, hope and light.

And of course, the logical cynic will point out that even the invitation to ‘come see the oxen kneel’ is purely hypothetical – there’s no one actually talking to the speaker, there’s no invitation, he’s talking to himself, or at best to us. And he doesn’t venture further than hope, and even if he did then he would be disappointed.

But then the Romantic poet would simply smile and read the poem again, and savour the fact that Hardy has chosen to end it with hope, which makes it far more prominent than the doubt.

And Hardy’s speaker may be old and cynical, but he says that if the invitation came, he would venture out in spite of everything. And each time you and I read the poem or listen to it, it’s as if a part of us goes with him, out into the gloom, as an act of faith, in search of magic, in spite of the voice of doubt.

The Oxen

by Thomas Hardy

Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock.

‘Now they are all on their knees,’

An elder said as we sat in a flock

By the embers in hearthside ease.

We pictured the meek mild creatures where

They dwelt in their strawy pen,

Nor did it occur to one of us there

To doubt they were kneeling then.

So fair a fancy few would weave

In these years! Yet, I feel,

If someone said on Christmas Eve,

‘Come; see the oxen kneel

‘In the lonely barton by yonder coomb

Our childhood used to know,’

I should go with him in the gloom,

Hoping it might be so.

1915

Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy was an English novelist and poet who was born in 1840 and died in 1928. He was best known for his novels, most of which were set in the West Country of England, which he fictionalised as ‘Wessex’, taking the name from the old Anglo-Saxon kingdom. But he thought of himself first and foremost as a poet, writing poetry throughout his adult live and continuing to publish it after he gave up on novel writing. After his death his ashes were buried in Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey, and his heart was buried in Dorset, with his first wife, Emma.

A Mouthful of Air – the podcast

This is a transcript of an episode of A Mouthful of Air – a poetry podcast hosted by Mark McGuinness. New episodes are released every other Tuesday.

You can hear every episode of the podcast via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite app.

You can have a full transcript of every new episode sent to you via email.

The music and soundscapes for the show are created by Javier Weyler. Sound production is by Breaking Waves and visual identity by Irene Hoffman.

A Mouthful of Air is produced by The 21st Century Creative, with support from Arts Council England via a National Lottery Project Grant.

Listen to the show

You can listen and subscribe to A Mouthful of Air on all the main podcast platforms

Related Episodes

The Unquiet Grave – Anonymous

Episode 22 The Unquiet Grave Mark McGuinness reads and discusses the anonymous ballad, ‘The Unquiet Grave’.Poet AnonymousReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessThe Unquiet Grave Anonymous ‘Cold blows the wind to my true love,And gently drops the rain,I never had but...

Organza by Selina Rodrigues

Episode 21 Organza by Selina Rodrigues Selina Rodrigues reads from ‘Organza’ and discusses the poem with Mark McGuinness.This poem is from: Ferocious by Selina RodriguesAvailable from: Ferocious is available from: The publisher: Smokestack Books Bookshop.org: UK...

Adlestrop by Edward Thomas

Episode 20 Adlestrop by Edward Thomas Mark McGuinness reads and discusses ‘Adlestrop’ by Edward Thomas.Poet Edward ThomasReading and commentary by Mark McGuinnessAdlestrop by Edward Thomas Yes. I remember Adlestrop —The name, because one afternoonOf heat, the...

The post The Oxen by Thomas Hardy appeared first on A Mouthful of Air.

Visit Podcast Website

Visit Podcast Website RSS Podcast Feed

RSS Podcast Feed Subscribe

Subscribe

Add to MyCast

Add to MyCast